The Law School's Commitment to Free Expression

Freedom of expression is a core element of the history and culture of the University of Chicago and the Law School. Law School faculty have been an integral part of developing the policies and procedures that have made the University a national model for academic free expression.

Free Expression Timeline: 1891-Present

1891

William Rainey Harper is named the University’s first president, bringing with him a then-unorthodox style of open scientific inquiry to the campus culture. This philosophy of open inquiry serves as the foundation of University’s rich history of free expression.

1902

Harper said free expression is a fundamental part of the University and that “this principle can neither now nor at any future time be called in question.”

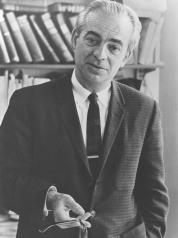

1967

Universities across the country feel pressure to take stands on social and political issues. In response, the University of Chicago taps Law School professor and First Amendment scholar Harry Kalven Jr. to chair a committee to research alternatives and issue a report. That process leads to a seminal document—the Kalven Report—stating that if the University takes any collective position, it would be akin to censuring those who disagreed with that position.

“The neutrality of the university as an institution arises then not from a lack of courage nor out of indifference and insensitivity. It arises out of respect for free inquiry and the obligation to cherish a diversity of viewpoints.”

Kalven Report

2014

Professors from the Law School served as chairs of committees that craft influential reports on free expression:

David A. Strauss, the Gerald Ratner Distinguished Service Professor of Law, serves as committee chair for the Ad Hoc Committee on Protest and Dissent, which is created in response to protests taking place at the University of Chicago Medical Center.

Geoffrey R. Stone, the Edward H. Levi Distinguished Service Professor of Law, is appointed to chair the Committee on Freedom of Expression, which produces a report that comes to be known as the Chicago Principles. The report lays out how the university has and will continue to treat free expression: Debate is welcomed, students can vigorously discuss even the most offensive ideas, and it’s not the university’s place to judge student’s ideas nor suppress their speech.

Though the Chicago Principles were meant for the University of Chicago, other universities took notice. Many have adopted the Chicago Principles or used the Chicago Principles as a model in developing their own policies.

“What makes UChicago special is that in all historical circumstances, it has backed the principle of free speech and supported students, faculty, and speakers in their ability to set forth what they believe to be appropriate positions. We were unique and powerful in doing that.”

Geoffrey R. Stone

2017

The Disruptive Conduct Report, also known the Picker Report, is created. Another major report on free expression, this report comes via the Committee on University Discipline for Disruptive Conduct, chaired by Randal C. Picker, the James Parker Hall Distinguished Service Professor of Law at the Law School.

The Picker Report says students are within their rights to protest and object to speech so long as they don’t block or disrupt the ability of others to speak or hear a speaker. This rule combats what Kalven called the “heckler’s veto,” where a speaker is silenced, drowned out by noise, or threatened to the point of no longer speaking.

2023

The University of Chicago launched the Forum for Free Inquiry and Expression, which aims to promote the understanding, practice and advancement of free and open discourse throughout the University and beyond, while addressing present-day challenges. The University taps Law School Professor Tom Ginsburg to lead this initiative as faculty director. Ginsburg is the Leo Spitz Distinguished Service Professor of International Law, Ludwig and Hilde Wolf Research Scholar, Professor of Political Science.

The Forum will reach outside the Law School and across the University, as thinking people must be able to express ideas—even unpopular ideas—and hear criticism, even when it stings, Ginsburg says. With more younger people feeling the fear of what happens if they say the wrong thing, he wants to be proactive and positive in teaching free expression and why it’s essential to society, showing that it’s sometimes essential to speak freely through the fear.

“For students, especially … expressing oneself does not come easily or automatically. It is not simply the absence of constraint which allows us to engage in deep expression. Instead, the University really is required, in my view, to actively construct opportunities for interrogation of ideas and the exchange of views across difference.”

Tom Ginsburg

Learn more on the history of free expression at the University of Chicago at the University’s free expression web site.