The Law School Stories You (Probably) Haven't Heard

The professor who turned famous cases into poetry. The students who decided to teach their own classes on “fragments of the law.” The Shakespeare-loving death-penalty scholar who spent decades swapping letters with Katharine Hepburn. The 1904 alumna and her years-long love triangle with two high-profile UChicago women.

The Law School has always enjoyed a rich history, one marked by expansive inquiry, colorful personalities, and new ways of thinking. Those values are evident in the Law School’s big moments—but, often, they can also be seen in some of the lesser-known stories that have grown from the community’s passionate devotion to ideas, people, and the school itself.

For the past three and a half years, we’ve been sharing some of these stories in our occasional “Throwback” series. In this issue of The Record, we offer excerpts of a few of our favorites.

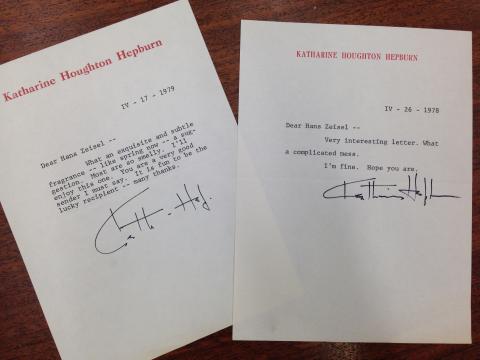

Zeisel and Hepburn: A Tale of Lavender Water, Shakespeare, and Capital Punishment

In early 1950, not long after taking his daughter Jean to see Katharine Hepburn play the heroine Rosalind in Shakespeare’s As You Like It on Broadway, future Law School Professor Hans Zeisel wrote the actress a letter offering notes on her interpretation of a line in a scene with the character Sylvius.

“You are undoubtedly right about the Sylvius scene,” Hepburn replied in a typed letter that March. “So much has been cut out of the scene that it is very difficult to know exactly how what remains should be played as Sylvius must understand her somewhat as he ends the scene saying, ‘Call you this railing?’ However, I think the truth probably lies somewhere between the two, and I am glad you took the trouble to write to me about it.”

Thus began a decades-long correspondence marked by Zeisel’s cordial commentary on Hepburn’s work, her gracious appreciation for his notes and gifts of lavender fragrance, and occasional intellectual musings. The letters, about a dozen of which are part of the Hans Zeisel Papers at the Regenstein Library’s Special Collections Research Center, document a predigital connection between Law School intellect and Hollywood celebrity that was fueled, at least in the beginning, by a shared fondness for the Bard.

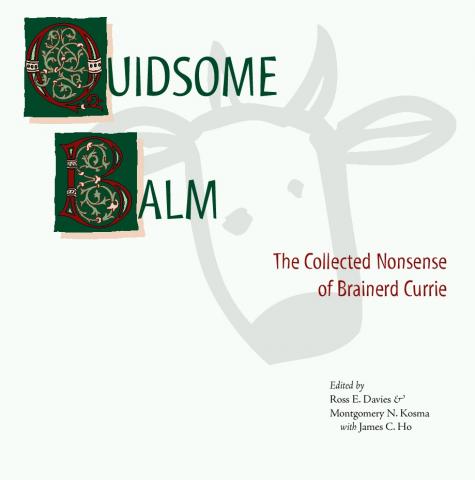

For the Shame of Rose of Aberlone

It isn’t every day that one encounters a poet/law professor, much less one who has employed 350 lines of comic verse to toast contracts law, the doctrine of mutual mistake, and a 19th-century tussle over an unexpectedly pregnant cow.

But in the 1950s, the Law School had Brainerd Currie, a noted scholar on conflicts of law, the father of the late Professor David P. Currie—and, as it so happened, a writer of rhymes laced with witty commentary on the law and legal education.

“I am sure that for Currie putting cases in poetic form . . . seemed as natural a thing to do as briefing them,” wrote Mercer University law professor Jack L. Sammons in the introduction to Quidsome Balm: The Collected Nonsense of Brainerd Currie, a seven-by-seven-inch book published by The Green Bag in 2000. “For Brainerd’s love of verse developed at the same time as his love for the law.”

Sophonisba in Love

It was the summer of 1928, and Sophonisba Breckinridge was in love. Times two.

The educator and social reformer, who had become the Law School’s first female graduate in 1904, was traveling with one woman and desperately missing another. And both, like Breckinridge, were influential women on the University of Chicago campus: Marion Talbot, who had served as the University’s Dean of Women before retiring in 1925, and Edith Abbott, Dean of the School of Social Services Administration that she and Breckinridge had cofounded.

“I don’t see how I can go on tomorrow,” Breckinridge wrote to Abbott that May as she traveled to Europe with Talbot. “I can think only of how good you are to me, and how I am so foolish and uncertain and disagreeable. I think you understand, though, dear.” The story of what appears to be a decades-long UChicago love triangle—marked by an evocative intertwining of intellectual and personal devotion, a fraught tussle for Breckinridge’s affections, and quiet acknowledgments that stopped short of actually labeling the women lesbians—was discovered by University of Montana history professor Anya Jabour, who had been researching Breckinridge for several years and is the author of a forthcoming book on Breckinridge.

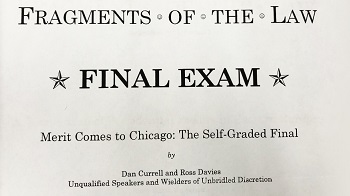

Fragments of the Law

Nearly 21 years ago, during the spring quarter of their third year, a small group of University of Chicago Law School students decided to teach each other a series of lunchtime law classes. One student spoke about presidential powers in Eastern Europe, and another showed clips from Warner Bros., The Dukes of Hazzard, and old Buster Keaton films for a session on the law of the chase. Two women—one married and one engaged, both to classmates—lectured on the laws of broken engagements.

There were syllabi and handouts and vague promises of food, although all these years later it’s hard to say whether the vodka and brown bread, popcorn and candy, or cake and champagne actually materialized. It’s hard to say, even, who first suggested the offbeat project—although most people are fairly sure it was Ross Davies and Dan Currell, both ’97—or whose idea it was to assign final grades by asking each student to toss a single-sheet exam onto the library steps, which were marked with scores of varying respectability.

What the dozen or so participants, mostly members of the Class of 1997, do remember is this: Fragments of the Law was quintessentially UChicago, rich with humor, tightknit collegiality, and the fruits of unbounded curiosity. The legal discussions that unfolded in each class were real, but so was the laughter. And some two decades later, it’s a thread of Law School history that remains lodged in the minds of its participants—albeit in various fragments of detail—as a quirky reminder of an academic culture that taught them the value of expansive, nonjudgmental inquiry and the virtue of clever amusement.

“The project was simultaneously really silly and really serious, and like many things, I think it came out of talking in the Green Lounge,” said Davies, who coyly denies leading the charge. “The faculty knew we were doing this. The administration was perfectly fine letting us use a classroom. The Law School is an intellectually entrepreneurial culture, and this is the kind of thing our instructors modeled for us: if you have a good idea, do something with it, and do it well. Do it thoroughly and in a disciplined way. And so this Fragments of the Law thing, yes, it was sort of a silly joke. But at our law school, we do these things right—including the nonsense. And that’s what it was: very highly refined nonsense.”