Zeisel & Hepburn

Throwback Thursday is an occasional feature offering glimpses into the Law School’s rich history.

In early 1950, not long after taking his daughter Jean to see Katharine Hepburn play the heroine

Rosalind in Shakespeare’s As You Like It on Broadway, future Law School Professor Hans Zeisel wrote the actress a letter offering notes on her interpretation of a line in a scene with the character Sylvius.

“You are undoubtedly right about the Sylvius scene,” Hepburn replied in a typed letter that March. “So much has been cut out of the scene that it is very difficult to know exactly how what remains should be played as Sylvius must understand her somewhat as he ends the scene saying, ‘Call you this railing?’ However, I think the truth probably lies somewhere between the two, and I am glad you took the trouble to write to me about it.”

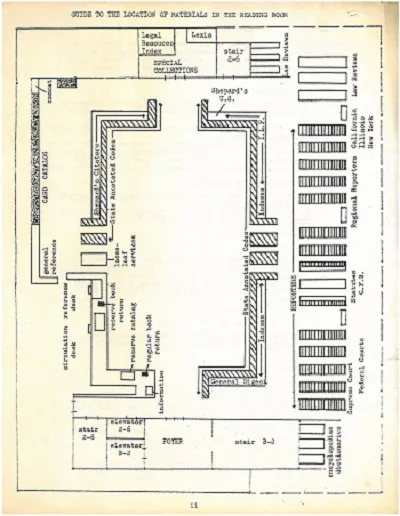

Thus began a decades-long correspondence marked by Zeisel’s cordial commentary on Hepburn’s work, her gracious appreciation for his notes and gifts of lavender fragrance, and occasional intellectual musings. The letters, about a dozen of which are part of the newly  processed Hans Zeisel Papers, available at the Regenstein Library’s Special Collections Research Center, document a pre-digital connection between Law School intellect and Hollywood celebrity that was fueled, at least in the beginning, by a shared fondness for the Bard. The entire collection—91.5 linear feet of material that became available in September—includes 173 boxes of Zeisel’s writing, research, correspondence, and more.

processed Hans Zeisel Papers, available at the Regenstein Library’s Special Collections Research Center, document a pre-digital connection between Law School intellect and Hollywood celebrity that was fueled, at least in the beginning, by a shared fondness for the Bard. The entire collection—91.5 linear feet of material that became available in September—includes 173 boxes of Zeisel’s writing, research, correspondence, and more.

“It was quite formal—he was the fan and she was the great actress,” said Zeisel’s daughter, Jean Richards, a stage actress who lives in Rockland County, New York. “But I guess because he was a professor, and perhaps because he cared about and knew Shakespeare, she answered him. She seemed to have taken him seriously, and I’d imagine that she was quite pleased that he was such a fan. But that relationship of fan to great actress always stayed.”

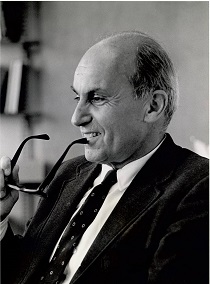

Zeisel, a sociologist and lawyer who was an authority on juries, capital punishment, and market survey techniques, joined the Law School faculty in 1953 to collaborate with Professor Harry Kalven, Jr. on a study of the American jury system funded by the Ford Foundation. Zeisel retired in 1974 but maintained an office at the Law School and continued to write, consult, and do research. He fervently opposed the death penalty; his letters with Hepburn, in fact, appear to have fizzled in 1989 over differing views on capital punishment before resuming in 1992, the year he died.

“That of course would have been a big rift—the death penalty was his main pro bono passion,” Richards said. “He wrote so many papers on capital punishment, how it wasn’t a deterrent. He felt that no civilized country should have it, that it was a shame and that it was awful. In fact, two days before he died, he was still working on an anti-death penalty study.”

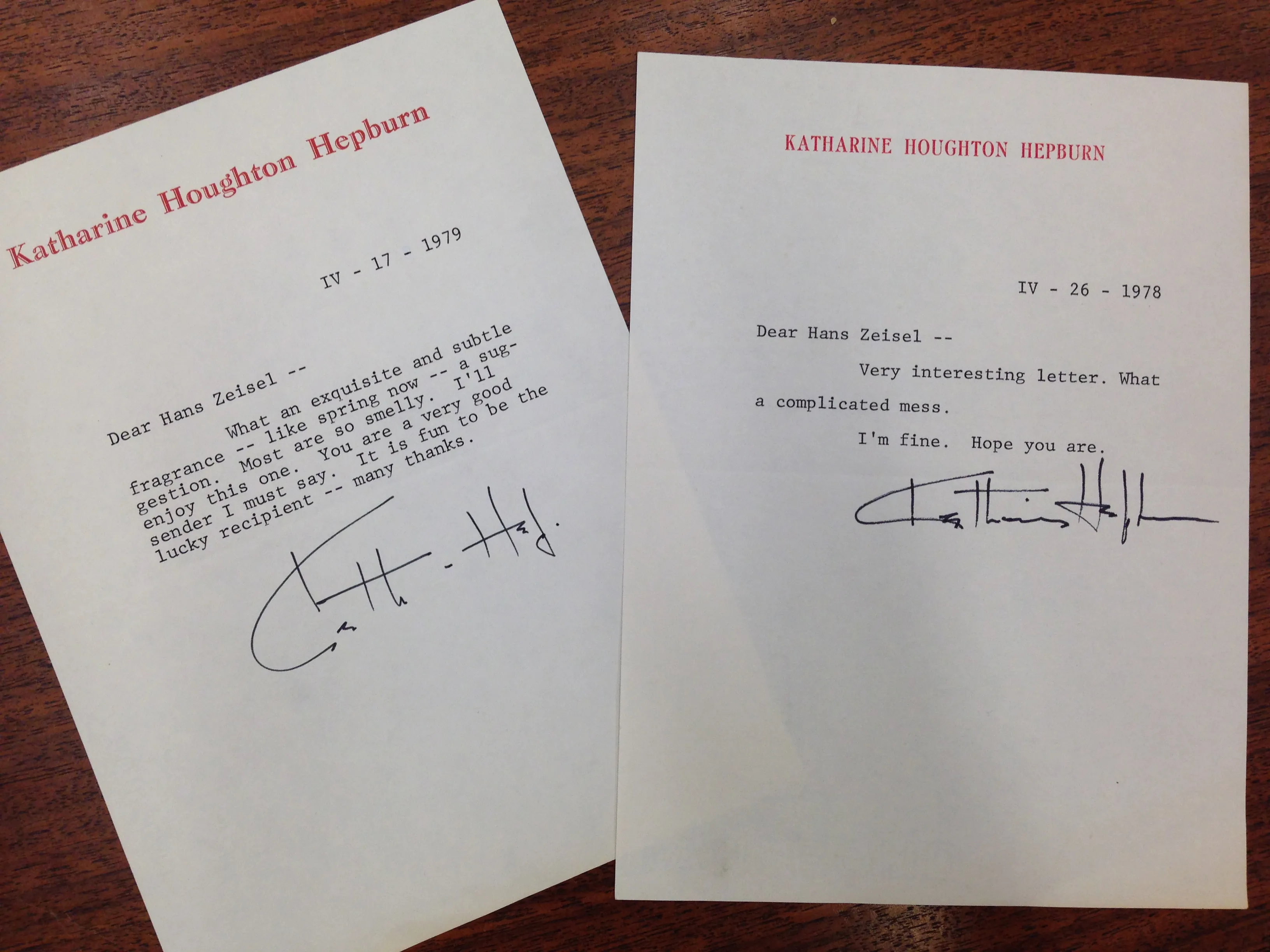

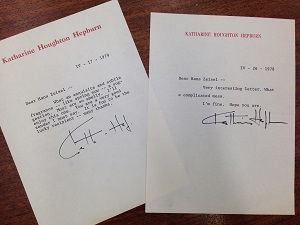

Exchanged between 1950 and 1992, the letters, only some of which are preserved in the collection, maintain an air of formality; although it appears the two may have met in  person, the relationship was one of pen pals. Many of his notes are typed on Law School letterhead, and many of hers are written on personal stationary emblazoned in red with her full name, Katharine Houghton Hepburn. The topics range from small talk to deeper social commentary.

person, the relationship was one of pen pals. Many of his notes are typed on Law School letterhead, and many of hers are written on personal stationary emblazoned in red with her full name, Katharine Houghton Hepburn. The topics range from small talk to deeper social commentary.

“If you are up to it, here is a bit more about my idea to assess the individual and social costs of bringing unwanted children into the world,” Zeisel wrote in January 1983 to the four-time Oscar winner, the daughter of a birth control activist and herself a public supporter of Planned Parenthood. “In the attached N.Y. Times column, Tony Lewis does precisely that for the children’s lunches. I would get in direct touch with the Planned Parenthood people, but somehow I thought that if you did it, having done so much for them, there would be much weight behind it.”

The following month, he sent a short note, as well as a copy of his 1983 book, The Limits of Law Enforcement, which argued that society should rely less on law enforcement to reduce crime and focus more on educating and guiding young children.

February 4, 1983

Dear Katharine Hepburn,

I am worried about your well being. I am sending you my new book; it is a new look at an old problem. You might care to browse through the first 88 pages, if you have nothing better to do.

With kind regards,

Yours,

Hans Zeisel

A few weeks later, she sent a short thank you:

II-23-83

Dear Hans Zeisel:

My well being is fine—just a really badly smashed ankle—But almost mended—and it works.

Thanks for the book and the bittersweet.

Katharine Hepburn

From a Love of Theater

Before he became a lawyer or a sociologist, Zeisel, who was born in Czechoslovakia but grew up in Austria, wanted to be an actor. As a teen in Vienna, he and his friends worked as claqueurs—professional applauders. Their job was to sit in the audience and, when the tenor started to sing his aria, begin the applause.

“I don’t think he got paid, but that’s how he got in to see all the operas for free,” Richards said.

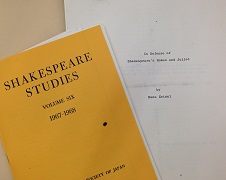

He also loved Shakespeare, and his daughter said that one of his proudest papers wasn’t legal scholarship but an analysis of Romeo’s motives. That essay, “In Defense of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet,” was published in the 1967-68 volume of Shakespeare Studies, a journal by the Shakespeare Society of Japan.

He also loved Shakespeare, and his daughter said that one of his proudest papers wasn’t legal scholarship but an analysis of Romeo’s motives. That essay, “In Defense of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet,” was published in the 1967-68 volume of Shakespeare Studies, a journal by the Shakespeare Society of Japan.

His correspondence with Hepburn grew from this love; his admiration for her came later.

“At first, it was about Shakespeare and what he thought was a misunderstanding of a line,” Richards said. “But as they corresponded, he definitely became a fan, and I’d even say he was a ‘stage-door Johnny’—a fan who waits at the stage door to bring a star flowers, not that he did that literally.”

Richards—the daughter of the professor and his wife, the industrial designer Eva Zeisel, who was known for her work with ceramics—remembers her father talking about the letters, which she said were “rather a thrill.” (Incidentally, the actress was not the only household name with whom he corresponded; he also exchanged letters with several US Supreme Court justices, as well as Eleanor Roosevelt and Coretta Scott King. The death penalty was often the subject of such correspondence). Many of the letters from Hepburn are short and, because some are missing from the collection, the references are not always clear:

IV-26-1978

Dear Hans Zeisel –

Very interesting letter. What a complicated mess.

I’m fine. Hope you are.

Katharine Hepburn

In 1979, Zeisel sent her a bottle of lavender water—a gift he appears to have sent again several years later after she ran out.

IV-17-1979

What an exquisite and subtle fragrance – like spring now – a suggestion. Most are so smelly. I’ll enjoy this one. You are a very good sender I must say. It is fun to be the lucky recipient – many thanks.

Katharine Hepburn

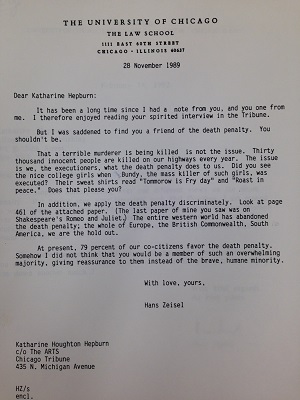

The correspondence, however, faltered in 1989, when Hepburn expressed support for capital punishment.

The correspondence, however, faltered in 1989, when Hepburn expressed support for capital punishment.

“I was saddened to find you a friend of death penalty,” Zeisel wrote that November. “You shouldn’t be. That a terrible murderer is being killed is not the issue. Thirty thousand innocent people are killed on our highways every year. The issue is we, the executioners, (and) what the death penalty does to us. Did you see the nice college girls when Bundy, the mass killer of such girls, was executed? Their sweatshirts read ‘Tomorrow is Fry day’ and ‘Roast in peace.’ Does that please you? In addition, we apply the death penalty discriminately. Look at page 461 of the attached paper. (The last of mine you saw was on Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet.) The entire western world has abandoned the death penalty: the whole of Europe, the British Commonwealth, South America, we are the hold out.”

Still, a little more than two years later, Zeisel resumed contact after seeing an interview she had done with Phil Donahue.

February 14, 1992

Dear Katharine Hepburn,

We stopped corresponding over our different views on the death penalty. But having seen your interview with Phil Donahue, I am moved to write you a letter with two-fold congratulations: First, to your triumph over Parkinson’s disease and secondly, for your put-down of that oaf by courageously sticking to your atheist position. Not many public figures would dare do this.

One more question. (I will not reveal the answer to anyone.) Did you really not know your interviewer’s name, or did you just superbly put him down another notch?

With kind regards,

As ever yours,

Hans Zeisel

Less than a month later, Zeisel died. But these snippets of his correspondence with Hepburn highlight two of his life’s greatest passions: his opposition to capital punishment, and Shakespeare.

“He was an unbelievably intelligent man with a wide variety of interests,” his daughter said. “And he was passionate about his work.”