Hidden Treasures: Law Library Unearths Original Letter from Marshall to Washington—And More

On March 26, 1789, 22 days after the newly ratified US Constitution took effect, future Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall sent a letter to George Washington at his Mount Vernon estate, where the president-elect was waiting for Congress to count the votes of America’s first electors.

It was, in many ways, an unremarkable note from a Richmond lawyer to his powerful, land-owning client, merely the latest in an ongoing conversation regarding Washington’s disputed claim to a piece of land on the banks of the Ohio River. But it was also one founder writing to another: a constitutional defender who would help shape the nation’s legal system advising the man who would soon assemble the nation’s first cabinet, oversee the creation of a national government strong enough to navigate partisan debate and suppress the Whiskey Rebellion—and whose property holdings in the Ohio River Valley were already helping push the burgeoning nation west.

It was history, living and breathing among the syllables of routine correspondence.

Which is why when Sheri Lewis, the director of the University of Chicago’s D’Angelo Law Library, opened an unfamiliar hardbound volume from the library’s Rare Book Room last summer and glimpsed Marshall’s 227-year-old letter—the original—pasted carefully inside, her first thought was, “Oh—wow.”

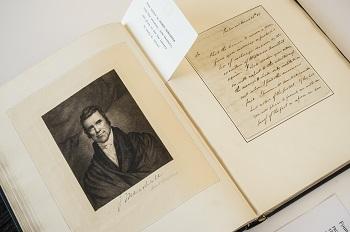

What’s more, the handwritten missive wasn’t alone. The carefully constructed album that had protected it for nearly six decades, maybe more, bristled with 18th- and 19th-century Supreme Court history, mostly hand-drawn portraits and letters signed by early justices, men like John Jay, Oliver Ellsworth, Samuel Chase, Salmon P. Chase, and Oliver Wendell Holmes.

And for years nobody at the University of Chicago Law School knew it was there.

* * *

There had been clues: an old catalog entry in the D’Angelo’s records; a note in an online database maintained by the National Archives; a plaque on the library’s sixth floor honoring the album’s donor, albeit for a different generosity; and a couple of 1958 articles in back-to-back issues of the University of Chicago Law School Record. It had been the articles that ultimately led Lewis and her team to the well-preserved, but temporarily forgotten, collection in July.

“It took me awhile to really absorb how much is in here,” Lewis said one morning in early 2017, as the D’Angelo’s librarians were preparing to send the 154-page album to the central University of Chicago Library to be fully digitized. “Every piece of parchment in this book tells a story.”

It had been a busy several months since Lewis first saw the volume. In that time, she and her team created an inventory of the collection, examined it with a preservation librarian and Law School scholars, and worked to unravel the mysteries of the album, which had been given to the Law School in the late 1950s by a colorful Chicago hotelier, Louis H. Silver, ’28.

The discovery was thrilling and unexpected but, for librarians and scholars versed in archival research, it wasn’t a shock. Library science has evolved significantly since the late 1950s; back then, there were no digital inventories and few finding aids—new items were catalogued and added to the shelf. As a result, the Supreme Court collection was, in fact, never truly lost: it was well-preserved and findable to those who went looking—it’s just that, after a while, there was nobody at the Law School who would have known about it without looking. History, after all, is a decidedly human affair that takes on a slightly different shape for each generation, molded by a combination of perspective, whim, and fortuity. People discover, forget, and rediscover; they choose what to protect, display, study, and discuss—and all of this ultimately shapes the historical narrative, often leaving a trail of breadcrumbs along the way.

“As historians, we tell our stories and build our analyses based on the evidence we have,” said Alison LaCroix, the Robert Newton Reid Professor of Law and a legal historian who was among the first to examine the rediscovered collection. “There’s always this question of what has been preserved, and why it’s been preserved. Sometimes things that are ‘lost’ don’t stay lost, and when we find them, we have new evidence. But what’s interesting, and important to remember, is how much of it is chance.” It was the point, she noted with a laugh, of the final number in the musical Hamilton, “Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story,” which centers on the twists of fate that ultimately shape one’s legacy.

“You think of history as being this thing that comes in nice, tidy boxes,” said William Baude, the Neubauer Family Assistant Professor of Law and a scholar of constitutional originalism who also has examined the collection. “But it doesn’t. There are things that we don’t know are out there—and things that we know are out there but don’t know we have.”

Before the Law School’s discovery, historians actually knew that Marshall had written to Washington on March 26, 1789; current-day researchers just didn’t know where the note was or what it said. Its entire public record was reflected in a short entry in the National Archives’ Founders Online database: “To George Washington from John Marshall, 26 March 1789 [Letter Not Found].” Other letters in the series had been catalogued as part of the Papers of George Washington at the University of Virginia and incorporated into Founders Online—including Washington’s April 5, 1789, reply to Marshall, which began, “Sir: I have duly received your letter of the 26 Ulto . . . ” (Note: Ulto is an abbreviation of the Latin ultimo mense, used in correspondence at that time to say “last month.”) Also included in the database: the March 17, 1789, letter from Washington that prompted Marshall’s March 26 reply.

“I think for me part of the excitement is that nobody knew what this March 26 letter said, and now we do,” said LaCroix, an expert in early American history. “But also, like most historians, I have a fascination with holding the real things. I was almost fearful in a way when Sheri brought it to my office and let me keep it for a day or two. I thought, Can I really have this? It’s unique, it’s the only one, it’s its own thing.”

The album, bound in blue goatskin with gold tooling, is filled with strokes of history, each with the potential to shade the narrative in some small way or even deepen our understanding of modern America. There are 60 drawings and 5 photographs of Supreme Court justices, various banking and legal documents, and 75 letters, including the one by Marshall and one in which future Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase speculates that Abraham Lincoln will win the upcoming 1860 election.

“In these manuscripts, we hear the voices of the country’s greatest jurists, recorded in their own hand, along with portraits that put faces to the authors,” said Bill Schwesig, the D’Angelo’s Anglo-American and Historical Collections Librarian. “The great effort and expense that Mr. Silver put into building the collection resulted in a beautiful and engaging artifact.”

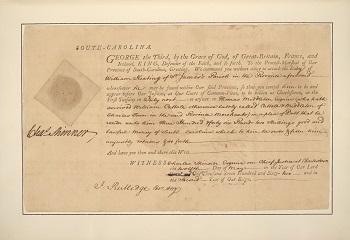

The written documents, which appear to be expertly affixed to preservation-quality pages, are arranged not by the order in which they were produced, but by the order in which the writer or signer served on the Supreme Court—starting with a 1783 letter written by the first chief justice, John Jay, and ending with a 1917 letter by Oliver Wendell Holmes. In between, the book holds a 1797 bank draft signed by the Supreme Court’s third chief justice, Oliver Ellsworth; an 1844 letter from Justice Peter Vivian Daniel to President John Tyler; and an 1823 note from Supreme Court Justice William Johnson to David Hosack, the physician who nearly two decades earlier had attended to Alexander Hamilton after his fatal duel with Aaron Burr. One of the oldest documents is a 1762 writ from King George III summoning a man named William Keating to court in Charleston, South Carolina; it was signed by the state’s provost marshal, John Rutledge, who more than 30 years later would serve—briefly—as the US Supreme Court’s second chief justice.

“When we first started looking for the collection this summer, we knew it was important,” Lewis said. “But, until we saw it, we didn’t have any sense of the breadth of it. This collection is unusual, and it is something nobody else has. And the fact that it was given to us by an alum is significant.”

Louis Silver, who had been an engineer before attending the Law School, was known as lively, astute, and discriminating. His personal collection of rare books—some 800 of which were purchased by the Newberry Library for a record $2.75 million after his death in 1963—was considered among the most impressive in the world. Even before the rediscovery, D’Angelo librarians knew of Silver: the Rare Book Room was named for him decades ago, when it first occupied a space on the Law School’s second floor. Silver had been generous to the University of Chicago, and although nobody knows why he donated the Supreme Court collection—or where it and its individual pieces had been in earlier years—librarians have speculated that he may have acquired, or even assembled, it expressly because he wanted the Law School to have it. At any rate, when the D’Angelo’s rare books collection moved in 2008 to the two glass-enclosed rooms on the sixth floor, Silver’s name went with it.

Quietly, so did the US Supreme Court Portraits and Letters collection, which ended up on a shelf in the western chamber, just feet from the plaque.

And there it slept until Lewis launched a research project this summer as a first step in rediscovering the rare books collection, which she and her team hope to strengthen and expand. That research turned up the 1958 Record articles, which referenced a “rare and important” collection that nobody in the 2016 law library had ever seen. One story contained the reprinted text of the Marshall letter, and the other included the text of the Chase letter.

“We didn’t even know it was assembled as a book—I first thought that the portraits and letters must have been displayed at some point in the Law School,” Lewis said. But she couldn’t find anything. She called retired D’Angelo Director Judith M. Wright; she, too, was stumped.

Finally, a member of the library’s staff found a promising entry in the library catalog. It was simple but accurate: “United States Supreme Court; portraits and autographs [collected by Louis H. Silver].” The call number led them to a shelf in the western chamber of the sixth-floor Rare Book Room.

And just like that, John Marshall’s words were back.

* * *

George Washington, Esquire

Mount Vernon

Richmond March 26th 89

Sir:

I had the honor to receive a letter from you enclosing a protested bill of exchange drawn by the executors of William Armstead esquire. I shall observe your orders, sir, with respect to the collection of the money. I shall only institute a suit when I find other measures fail. I presume Mr. Armstead’s executors had notice of the protest. If they had, you will please to furnish me with some proof of the fact or inform me how I shall obtain it. Should a suit be necessary this fact will be very material.

Your caveat against Cresap’s heirs is no longer depending. It was dismissed last spring under the law which directs a dismission if the summons be not served.

I wrote to you on this subject before that session of the court and supposed it to be your wish that it should no longer be continued.

I remain Sir

With perfect respect and attachment

Your obedient servant

(signed) John Marshall

“Just looking at this, we can assume that this is Washington’s copy,” LaCroix said one afternoon in December, as she and Lewis were looking through the collection with a visitor. “You can see that it has been folded and postmarked—and it’s stamped, ‘FREE,’ so Marshall must have had franking privileges because he was a government official.” (Franking privilege, which dates to 1775, allows public officials to send mail without a postage stamp. Marshall was the Richmond city recorder—and therefore a magistrate—as of 1785, and that may well have been the office that gave him free postage in 1789.)

Someone would have copied the letter for Marshall’s files, LaCroix said, which means that at some point there was a second version that hadn’t traveled the 95 or so miles between Richmond and Mount Vernon. “But this one,” she said, “is addressed to ‘George Washington, Esquire, Mount Vernon.’” She paused. “Because, really, what else would you have needed to write? This must have been his.”

To a historian’s eye, the letter is filled with little insights, reminders, and curiosities: from the role of the founders in westward expansion to the quirks of letter writing; Marshall, for instance, used 11 words to sign off, but abbreviated the last two: obedient servant.

It was a little detail, but one that had a humanizing effect. It was hard not to wonder what Marshall had been thinking and feeling as he wrote the letter, or to consider the swirl of activity that must have surrounded Washington as he read it. There was something fascinating, LaCroix mused, about touching what they’d touched, and seeing the curves of their handwriting, and reading the words they’d chosen.

“It’s a little window into the founding,” LaCroix said. “It’s a slice of life. Marshall and Washington are writing to each other as lawyer and client, and that’s a relationship that had been going on for a long time, too.”

It was a time of transition for the young nation: the US Congress had met for the first time on March 4, and they were on the verge of certifying Washington’s victory in the first presidential election. “He was reluctant to become president,” LaCroix said. “He’d been away from Mount Vernon for so long, and he wanted to be back there and be the gentleman soldier in retirement.” But Washington felt a sense of duty, and on April 16, he’d begin a weeklong procession to New York City, the nation’s capital, for his swearing-in on April 30.

“He was getting ready to process to be the chief magistrate of this unknown experiment,” LaCroix said. “It’s pretty cool to think about.”

Marshall was a force in his own right. He’d been a leading champion of the Constitution as a delegate to Virginia’s ratifying convention, and he’d fought especially hard for Article III, which provides for the federal judiciary. (Years later, in 1803, the first major case before Marshall’s Supreme Court would be Marbury v. Madison, which established judicial review.) But now, he was practicing law in Richmond—and trying to help Washington settle a dispute over hundreds of acres of land in the Ohio River Valley, property Washington had claimed in 1770 and had most likely earned for his service in the area during the French and Indian War.

It was a typical frontier dispute: another man built houses on Washington’s land in 1773, and now, years later, Washington was still sorting things out with the man’s heirs. (According to research that accompanies the Founders Online entry, it appears that the dispute wasn’t fully settled until 1834, when a court upheld the title in favor of a man who had purchased the land from Washington in 1798.)

What’s intriguing to LaCroix about the timeline, though, is that it began in British America and was eventually settled in the United States—an important reminder about the continuity of law.

“You look at this and you remember: it wasn’t that Americans invented law on March 4, 1789,” LaCroix said. “They already had British common law, and they had disputes that had been going on under the British Empire.”

It is impossible to know, of course, whether Louis Silver shared this fascination or even envisioned contemporary and future scholars probing these sorts of details when he donated the album sometime during or just before 1958. His intentions are one of the collection’s enduring mysteries.

“He was this extremely well-known collector of his time, but law wasn’t his major area of focus,” Lewis said. “And yet, he did collect this. He intentionally gave it to the Law School, even though much of the rest of his collection went elsewhere. To me, it suggests that he thought it was important that the Law School have this.”

Silver made the gift while he was still living—and he made it at a time when Americans’ interest in the Supreme Court was particularly high: Earl Warren was the chief justice and, just a few years earlier, the Court had ruled in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education. (Incidentally, Silver’s album arrived just a year or two before the Law School moved from Stuart Hall to the current building south of Midway. It is possible that the flurry of activity accompanying the move contributed to the album’s recession from collective memory, though Lewis notes that the library’s comparatively small staff—directed by a member of the faculty in those days—and its predigital cataloguing system probably played roles as well.) Either way, both the timing and topic were curious. Silver’s interests were broad: in 1958 and 1959, he’d donated science and technology books to the University of Chicago, and the collection acquired by the Newberry Library included valuable works in English and Continental literature and history. But there isn’t much indication that law was a top priority beyond the Supreme Court collection.

“Collectors collect things for different reasons, and—I don’t know—but you can imagine Mr. Silver thinking, I’m a lawyer and I’m really interested in Supreme Court justices, so let’s get all the documents we can pertaining to them.” LaCroix said. “But that could take so many different forms. He could have just been after the autographs. One of the letters, Roger Taney’s, is responding to someone who wrote [in September 1860] asking for his autograph. And Taney just sent it back with a note.”

LaCroix shook her head: “Of all the ones you’d want.” (Three years before sending the autograph, Taney had delivered the majority opinion in the landmark Dred Scott case, which held that black people, whether free or slave, could not claim US citizenship.)

But the Taney letter underscored another important point: motive aside, someone had collected these letters, portraits, and documents; and had taken care to preserve them regardless of writer or content; and had assembled them into one book, ensuring that, to some extent, they would be studied and considered together.

“This is the happenstance, and good fortune, of someone choosing to collect and preserve, and choosing to do it in a certain way,” LaCroix said.

This album, for instance, connected each writer to the Court, but also, at least in some cases, offered insight into other parts of their lives. LaCroix turned the pages until she found the 1762 summons that had been signed by John Rutledge.

“See here, in 1762, this is Rutledge as the provost marshal of South Carolina—it’s a future Supreme Court justice as a judicial official in the British Empire, carrying out writs signed by George III,” LaCroix said. “This, too, is a continuity we often don’t think about.”

Similarly, the album’s portraits captured some of the men as younger, or otherwise different, than the images we most often see. In the Marshall letter, Washington was a man eager to keep the land he’d claimed on the western frontier and Marshall was a practicing lawyer whose time on the Supreme Court was still a dozen years away.

“Sometimes the value in letters like these is that they tell us something we didn’t already know . . . but other times the value is that they make [the writers] real,” Baude said. “The artifacts bring them to life, and they’re more than abstractions in the computer. Seeing an original letter, you remember, too, that the writer actually had to sit down and write, and that the letter had to travel—and you remember how little they knew about what was going on [outside their geographic area]. You get a better emotional sense for how big the world is.”

What’s more, reading about pivotal events through the wizened eyes of hindsight, he pointed out, can offer up powerful reminders and even a lesson or two.

* * *

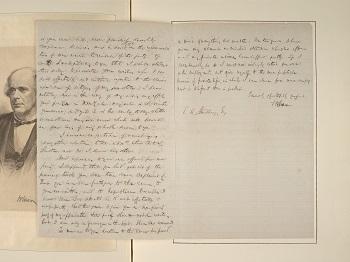

In 1860, Salmon P. Chase, the Ohio governor and a candidate for US Senate, wrote to a man named E. A. Stansbury about the upcoming presidential election. It had been a turbulent election cycle marked by deep divisions over slavery, a geographically fractured Democratic Party, and a contentious four-way race involving Abraham Lincoln, John C. Breckinridge (a cousin, incidentally, of the Law School’s first female graduate, Sophonisba Breckinridge, 1904), Stephen A. Douglas, and John Bell.

Chase, who would later become the Supreme Court’s sixth chief justice and whose face would appear on the now-defunct $10,000 bill, was an abolitionist lawyer who had represented runaway slaves. He seemed to favor Lincoln and speculated that the Illinois Republican would win—and that his election might bring an end to slavery in America.

But Chase couldn’t help but wonder: what comes next?

My dear friend,

Nothing in the future is even tolerably clear to me except the probability, approaching certainty, that Mr. Lincoln will be our next President, and that by his election the power of slavery in our country will be broken. What lies beyond I see not. I hope the Administration will be Republican, and that faithful Republicans will be called into the Cabinet, and that all will be well. To that end I shall honestly, sincerely and earnestly labor. I do not know Mr. Lincoln personally. All I hear of him inspires confidence in his ability, honesty and magnanimity. These qualities justify the best hopes, but we must remember that he has not been educated in our school, and may not adopt our ideas, therefore, either in selection of men or in the shaping of measures.

…

Faithfully your friend,

S.P. Chase

Any apprehension Chase might have felt was well placed, of course. The coming years would bring the secession of 11 southern states, a devastating civil war that would leave hundreds of thousands of dead, and Lincoln’s assassination. But the future would also bring the end of slavery, a fitful reconstruction, and an eventual return to national unity.

“We think of ourselves as confronting all these new circumstances, and we think, ‘Who knows what’s going to happen?’ But they felt that way in 1860, too,” Baude said. “We see that, in some ways, our problems aren’t as new as we think they are. In a way, we’ve been here before.”

All of this—the perspective, the opportunities to connect with founders and shapers of law, the chance to see the evolution of America and its legal system through the words of those who were there—have underscored the very mission that led Lewis and her team to the US Supreme Court Portraits and Letters collection in the first place.

“We were focused on advancing the rare books collection when we found this and, now, it’s a nice reminder of the value that this material brings to the Law School,” Lewis said. “We are looking for ways to continue making rare books more accessible to faculty, and to strengthen and build our offerings.”

Part of that means continuing to explore the existing rare books collection, which includes more than 2,800 items.

“After this,” Lewis said, “I can’t help but wonder what else we’ll find.”