Is This What Democracy Looks Like?

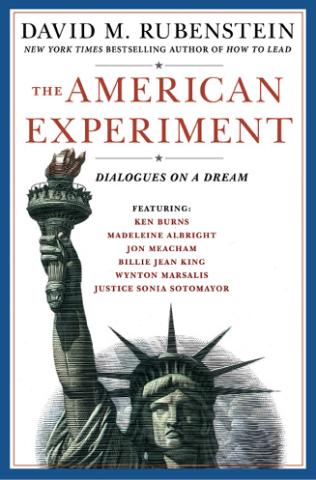

In the past four years, David Rubenstein,’73, has published three books of interviews. He has interviewed CEOs and founders to dig deep into the concept of leadership, and he has interviewed our greatest historians to more completely illuminate the American story. In his latest book, The American Experiment, Rubenstein explores the notion of how America’s founding ideas and spirit have developed in the arenas of democracy, culture, and innovation. Rubenstein writes that the factors that combined to create the United States, which he thinks of as “America’s genes,” had to be “present in the right degree at the right time [or] the country as we know it would not have been formed, survived, or evolved to its current state.” Rubenstein lists 13 genes, the first of which is democracy. In this interview, Rubenstein sits down with Tom Ginsburg, the Leo Spitz Professor of International Law, to discuss the history and meaning of democracy and what he believes are the threats to its future.

Tom Ginsburg: I want to start with you. How did you get so interested in American history? Have you always been interested in this, or did you come to it as an adult?

David Rubenstein: I was probably better in American history than I was in science, and naturally you gravitate to the things you’re better in. My love in life when I was growing up was history and politics, and so I gravitated toward wanting to work in government. I got a job working at the White House when I was very young, and when you work in the White House you do get a sense of history.

I’ve lived in Washington ever since I left the White House in 1981, and living here you get a sense of history as well. As a result of all that I guess I have a greater interest in history than maybe the average person my age, but it kind of came about by serendipity.

TG: With these books of interviews, and particularly the one on “the American Experiment,” you’re really reaching very broadly in terms of picking kinds of people to talk to. Who is the person that you interviewed that surprised you the most? What’s the most surprising thing you learned from these folks?

DR: This book is designed to say that the experiment, which began at the Constitutional Convention, and with the ratification of the Constitution, is one that’s still ongoing. No one really expected at that time that it would last as long as it has. Some people didn’t think it should last more than 20 years—that was Thomas Jefferson. I wouldn’t say anybody I interviewed was a surprise. One anecdote I think is in the book that may be emblematic of the problem we often have in learning history is that when [historian] Jill Lepore went to talk about her book to some kindergarten students, she asked them about the founding fathers. She said to them, “What do you think about the women in those days?” and the students said, “Well, there were no women in those days.” Which reflects the fact that men have been writing history for so many years. Really the book is about how America is this experiment that has worked better than some founding fathers thought, but still has not quite lived up to the rhetoric of the founding fathers’ documents in many ways.

TG: You talk about that longevity and you use this metaphor of “genes” that come together in this unique and somewhat historically contingent way in the United States to make the country what it is. Today we’re at this polarized moment with deep anxieties on a lot of different fronts, and I wonder if you think any of that is genetic as well.

DR: I used genes as a metaphor to say that all countries, like all people, have genes. There are probably thousands of American genes. I listed 13 that I thought were representative of the things in this country that people tend to agree on, though there are obviously some exceptions. I don’t know that there’s any one gene that I think is the most important American gene, but if I had to pick one, it’s the belief that democracy is a better form of government than any other form of government. We can define democracy different ways, but I think most people in this country would agree to that, whereas if you go to the Middle East or China or many parts of the world, they wouldn’t agree that democracy is the best form of government—in fact they really argue strenuously that it’s not. But you and I grew up believing that democracy was probably the best form of government, and we probably haven’t changed our minds, even though the views of many citizens in this country about what democracy is have changed dramatically.

TG: International organizations that rate democracies, as well as the Economist, have now downgraded the United States from being a full democracy to a flawed democracy in recent years, reflecting some of our struggles. Do you think that’s fair? What’s your view of the state of where we are in our democratic experience?

DR: If you want to live in a democracy that is more of a representative democracy than the United States, you can find other countries, for sure. But if you want to live in a gigantic economy that has all the other attributes and virtues of the United States, there aren’t that many other places you can live. It’s interesting that we have 46 million immigrants in this country, and no other country in the world has anything close to that. We have very few people leaving the country, and almost nobody leaves for reasons other than taxes. People don’t leave because they don’t like our democracy.

As a general rule, I think the democracy that we have created is one that the founding fathers probably wouldn’t completely recognize. They wouldn’t have thought the Supreme Court would be as important as it has turned out to be. And they probably didn’t expect the President would have turned out to be as important as he or she has turned out to be. But that’s the reality. The democracy we have now is probably under greater challenge than at any time since the early days of the Great Depression, when there were people who said that capitalism and democracy had failed, and we should go to a different form of government. But other than that, not since the Civil War has the basic, fundamental concept of our representative democracy and the way we operate been so much under challenge. Ironically, Donald Trump used to say he would look good on Mount Rushmore. And now that I think about it, maybe he’s right because he’s done more to energize people about democracy than anybody I’ve ever met. As you know, there is legislation now in Congress to change some things about the way the presidency operates, which he brought to our attention. In many ways, he taught us some of the weaknesses in our democratic system, unintentionally, of course, but if we can make some of the changes that people are thinking about, it might actually improve the democracy.

TG: When we look around the world and we look at these cases where you have democratic backsliding and then something happens to save the democracy, one of the things that we focus on is the role of unelected actors at those moments. For the politicians, it’s often not incentive-compatible for them to save the democracy. It’s these unsung bureaucrats—the people counting the votes in November 2020, the Capitol police on January 6 and such—that turn on the rule-of-law gene that you identified, the idea that you would just follow the law, no matter where it leads. So how can we sustain that? Is that sustainable, given the general declining trust that we see in American institutions?

DR:The decline in trust is very disturbing. The Congress is thought to be dysfunctional because it can’t get anything done, but it’s really reflecting the country. I think the country is split down the middle and, as a result, things that we had accepted as normal we no longer do. It used to be the case that after the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that people would be able to vote in a relatively unhampered way, but now we not only are not able to pass an extension of the VRA, we are retrogressing in many states. I’ve said before that if the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was put on the floor of the Congress today, I don’t think it could pass. I like to think that the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments could pass, but I’m not even sure about that. It’s because members of Congress are so afraid of social media on their side of the spectrum and so afraid of not being able to raise money from the far right or far left that people are unwilling to do things that would seem to be the most simple things in the world. How can you not pass the 1964 Civil Rights Act or the 1965 Voting Rights Act? But clearly we’re not going to do it.

TG: I do agree with you—I never thought of that before, but it’s really, really disturbing in terms of how polarized we’ve become.

DR: Take a look at what happened on January 6. At some point we may celebrate “January the Sixth” the way we celebrate “July the Fourth” because January 6 is a wake-up day. It made us realize our democracy is subject to enormous weaknesses. Let’s suppose Mike Pence had said, “Donald Trump, I’ve listened to him for four years, and I think he’s pretty persuasive, and I think he’s right.” As you know, the Constitution decides that if you can’t get a majority out of the Electoral College, you go to the House of Representatives, and there, the majority of the delegations were Republican. So Donald Trump could well have been elected. The system we have has got lots of flaws and the electoral system was not designed to be a democratic system to begin with. It was designed to keep democracy from coming forward.

TG: Hopefully, we will be able to fix it. Let’s talk about history. History itself has become a partisan battle, highly polarized with state legislatures getting involved. The way history is taught is a major, contentious issue in our democratic politics today. Do you think we need a founding myth to bring us together? Is it useful for such a diverse people to have founding myths?

“I used genes as a metaphor to say that all countries, like all people, have genes. There are probably thousands of American genes.”

David Rubenstein

DR: When you and I were in grade school, the founding fathers were treated like religious figures. They were thought to be, while not perfect, they were the people that gave us this country. Now there are people on the left who think that we should tear down the Washington Monument or the Jefferson Memorial because they were slave owners. You also have people on the right who basically think that if you try to teach people about slavery even in as bipartisan way as possible that that is considered inappropriate. There’s legislation in Congress right now—a billion-dollar bill—to provide civic education throughout the country, and it’s not likely to pass because the critical race theory concerns have blocked the Republicans from being willing to endorse this in any meaningful way. When this country was created, we had a fatal flaw, a birth defect called slavery, and we’re still living with it because much of what is going on now is about race. Much of the concern is about the fact that minorities are increasing at a population rate faster than Whites are, and the result is that we will be a minority-White country about 20 years from now. People see their power and authority being taken away and there’s resistance to it.

TG: We have some states that are already majority-minority. In California, for example, Hispanics are the plurality. At the the other end we have some relatively homogenous states where you have culture wars that are completely heated up. Do you think that we’re going to see increasing heterogeneity across states in the future with regard to the quality of our democracy and our shared understandings of the nature of the country?

DR: When John Kennedy ran for president, Richard Nixon said, “I’m going to campaign in all 50 states.” John Kennedy campaigned in about 45 of them. And the reason they did that was it wasn’t clear how every state would go. Today it’s clear how every state will go with the exception of no more than eight. So this country has become a situation where each state is a different country unto itself. In California, anything conservative is not going to get done. In Alabama, anything liberal isn’t going to get done. Each of these states are like their own countries, and they just have different genes than other states. Surprisingly, it’s not homogenized. Anybody can go across any state border, anybody can live wherever they want, but people who are conservative have tended to gravitate to the southern states, and people who are liberals have tended to gravitate to the coasts, and it doesn’t seem to be changing very much.

“If I could change anything in the Constitution, it would be to find a way to eliminate money in our campaigns, and you’d see the country would be so much different.”

David Rubenstein

TG: In some sense we’re a bunch of different countries.

DR: If Roe v. Wade is overturned, that will bring home to even more people how the states are really like little countries. If you’re poor and you live in a state that’s against abortion, you’re going to have to travel outside of the state or you can’t get or can’t afford the abortion. The country has lots of flaws in the way we’re operating right now, but I don’t see it changing anytime soon. If Donald Trump were to disappear from the scene, while he’s the ringleader, there always will be somebody that can replace him.

TG: This may be an unfair question to you, but if you could change one thing in the Constitution, is there something you would change to save our democracy, to put it on stronger footing?

DR: It’s very difficult, as you know, to change the Constitution. Most constitutions have been changed much more than ours has been changed. If I could change any one thing, it would be to figure out a way to eliminate money from politics and campaigns. Because what’s happened now is that some members of the House, particularly, are spending 40 percent to 50 percent of their time raising money. Why? Having more money scares off opponents, having more money enables you to buy subcommittees and committee chairmanships, having more money enables you to run a better or more financed campaign. Most importantly, now there’s no limit to how much money you can take away. Theoretically, you don’t use it for political purposes, but it’s a very elastic definition. So members of Congress are spending all this time raising money and they have to raise it from people on the far left or from the far right. Nobody is raising money from people in the center. And the far right and the far left are very small percentages of the overall electorate, and these are the people who are funding probably more than half of the money used in election campaigns. If I could change anything in the Constitution, it would be to find a way to eliminate money in our campaigns, and you’d see the country would be so much different.

TG: I want to come back to free speech and in the particular context of academia. Freedom of expression and freedom of inquiry are core values of this university. You’ve played a leadership role at several institutions of higher education. How do you see the role of universities in democracy at our current moment when we’re in what some have called a “post-truth society”? Do we have any special duties or obligations at this moment?

DR: I really value universities, because I think they are national assets. We are the envy of the world in higher education. But universities have their flaws, of course, and among them is that they are not all willing to let everybody speak when things that certain people are going to say are unpopular. The University of Chicago has stood out as the beacon among great universities as being willing to let people speak even when they’re saying something unpopular. But in certain well-known universities, you can’t get certain speakers on the campus without protests, which may even result in violence or cancellation of the speech. It’s a sad situation. Universities should be leading in this area, and in some cases we’re not leading anymore. The University of Chicago under Bob Zimmer’s leadership and some of his predecessors has really been a stalwart in this area. If the University of Chicago is known for anything, other than rigorously intellectual inquiry, it is that it really believes in the right to free speech and free expression. I think that’s an important tradition that we want to continue. I wish other universities were as bold in this area as the University of Chicago has been.

TG: Sometimes we get the feeling that we can come up with great research, but it would just get drowned in the public debate by the social media and such in the current media environment.

DR: In my book, I commissioned a public survey of American people by the Harris Poll organization and asked what were the most important rights and things that made people proud about being American. The highest right that people thought was important to being an American was the right to free speech. I wouldn’t have thought that was as important as the right to vote or the right to equal opportunities, but the right to free speech was the most important thing that Americans cited.

TG: Why do you think, then, that the culture seems to be pushing against that with so-called cancel culture—seeming to be so willing to attack people when they do engage in expression?

DR: In this society, everybody has a megaphone as a result of social media. And everybody feels that they’re entitled to do what they want to do, and we haven’t seen any social penalty for saying or doing outrageous things, by and large. So it’s an unusual phenomenon where people are upset about the country in many ways, but they don’t seem to be able to express in an articulate way what it is they exactly want to do, and why they think that everybody should listen to what they want. We don’t listen to people as much as we used to, and the cancel culture on the left and right means, “Let’s get rid of anything we don’t agree with.” Throughout organized history, every generation has said, “Wow, we were great, but the people coming after us, they’re not going to be as good and the country or civilization is going to fall apart.” This has been going on for thousands of years, and I suspect it will go on for another couple thousand. So, as two people who have gray hair, you and I, we are saying, “This country’s falling apart and look how bad it is.” The truth is, 20 years from now, our successors will probably say the same thing. This is a cycle that goes on for a while—are we worse off now than we were 20 years ago? I think we are worse off in things like cancel culture and worse off in in being unwilling to let people exercise some of their basic rights.

TG: At the end of the day, are you optimistic or pessimistic about the future of our democracy?

DR: I think anybody that’s an entrepreneur or been reasonably successful in their professional life is probably an optimist. Generally people who are successful probably are optimistic because they feel they got something done. They moved forward, they saw how they could change things, and they therefore think that it pays to be an optimist, not a pessimist. Therefore, I probably have a bias toward thinking that we’ll sort these problems out and, ultimately, the country will survive. But I probably am less optimistic than I was 10 years ago in many ways, in part because the events of January 6 and all the surrounding events make me realize that democracy is very fragile. We could easily have had a different outcome in the election if January 6 had been different.

TG: I have a broader question about two of your genes. One of them is capitalism, and we carry the water globally on the importance of capitalism. And the other is equality. The relationship between wealth inequality and democracy is a fundamental debate in democratic theory going back to the ancient Greeks: how do you ensure that some people don’t speak more than others?

Are the genes compatible? How do we sort out the tensions between those two genes?

DR: They’re not necessarily all compatible, no, of course not. Thomas Jefferson did a great thing with his Preamble, because it inspired people around the world and in this country to think that they have equal rights. But there never have been equal rights for all people, and I’m not sure we’re ever going to get it. Obviously when Jefferson wrote that famous sentence he was thinking about all White Christian men. He wasn’t thinking about people who were Jewish, wasn’t thinking about people who were Black, and he wasn’t thinking about women. But because he didn’t specifically say that, that language has taken on a meaning of its own and now we’re trying to live up to it. While most people will give lip service to the fact that they think that everybody should have equal rights, many people are not really willing to allow that to happen, to be honest. The rhetoric of the founding fathers is much better than the reality. One of the interesting things I’ve often thought about is how would the Constitution be different if, today, you took 55 White, Black, and Brown men and women from all parts of the country and of all economic statures and religions and put them together—what kind of constitution would you come up with? Because we’ve been living for a few hundred years with a Constitution that White propertied educated Christian men came up with. I just wonder what the government would look like if we had a much more diverse kind of Constitutional Convention.