An Unexpected Path and a Devoted Champion

In 1969, a man in his early 20s went before the local draft board in Evanston, Illinois, to declare his conscientious objection to war. And not just the conflict smoldering in Vietnam, but all war; it was a position born of his Roman Catholic faith and 12 years of Catholic schooling in Chicago’s northern suburbs.

It took a year, but he convinced the board that his beliefs were sincere and fixed; shortly after, the board exempted him from military duty and ordered him instead to spend two years working for an eligible nonprofit. It was up to the young man to find the job, so when a friend of a relative suggested he work as a nurse’s aide in the psychiatric department of Michael Reese Hospital, a now-defunct medical center in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood, he thought, Great, this works. It was an obvious enough choice: there was a long history, going back several wars, of conscientious objectors performing their alternate service in mental health wards. In fact, he would soon be one of three COs at Michael Reese.

And so it was that Mark J. Heyrman, now a clinical professor of law, found himself at the beginning of a road he hadn’t quite planned to travel—one that ultimately led to a four-decade career as the head of the University of Chicago Law School’s Mental Health Advocacy Project. The program, which originally focused on assorted cases involving mentally ill clients, now handles a mix of litigation and legislative advocacy, all built around improving the care and treatment of mentally ill persons.

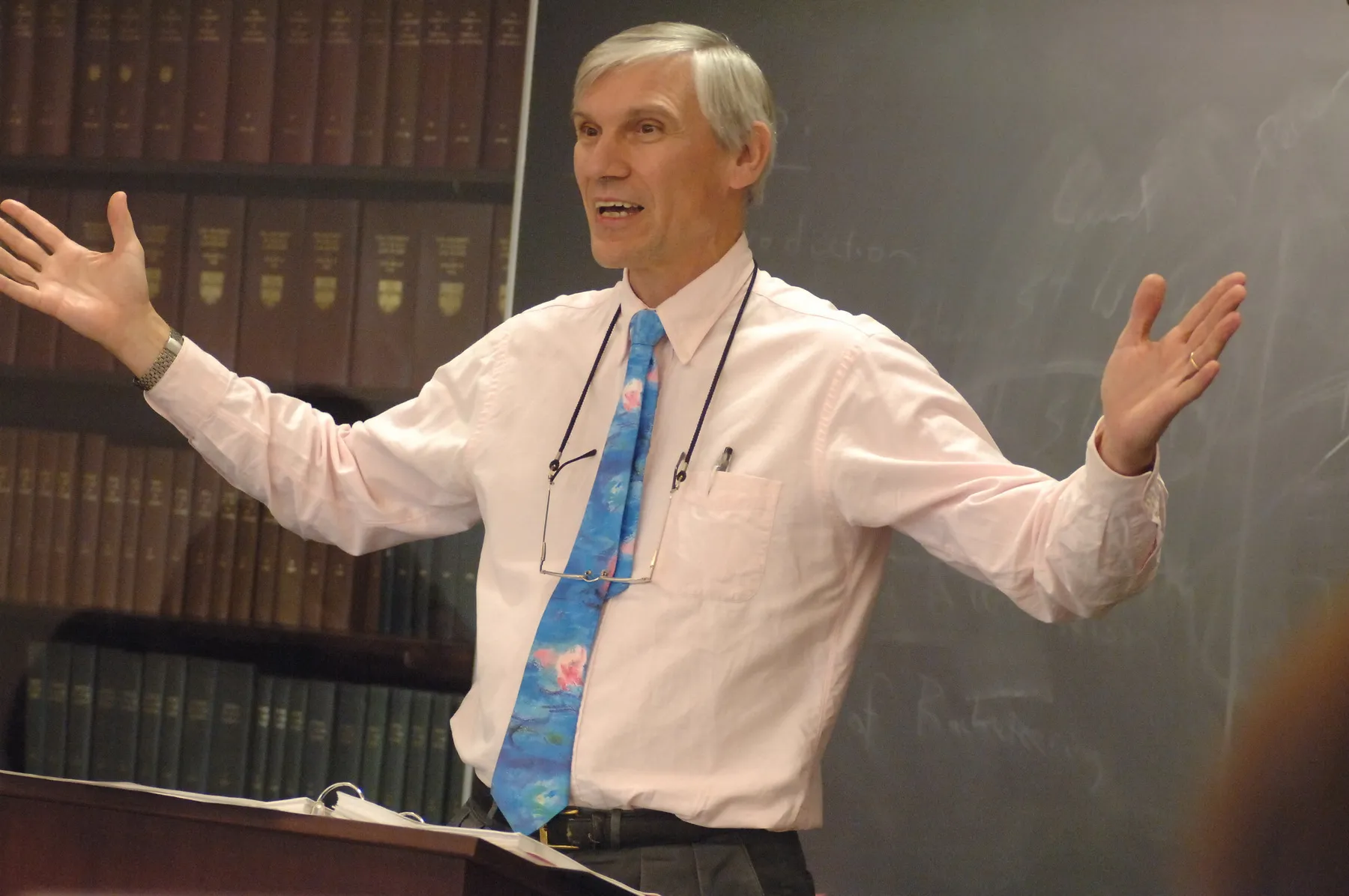

When he retires this summer—some 43 years after taking his first mental health case as a Law School clinic student, an assignment he was given because he’d worked in a psychiatric ward—Heyrman, ’77, will have devoted more than half of his life to both clinical legal education and mental health law. Over the years, he has litigated more than 1,000 cases, played a key role in shaping mental health policy in Illinois and across the country, and trained close to 300 Law School clinic students, pushing them to hone oral arguments, process complex ideas, and walk the delicate line between objectivity and compassion. He’s corresponded with former clients as they’ve rebuilt their lives, meeting them for lunch, exchanging holiday cards, and even once writing a law school recommendation for a man who, years earlier, had stood trial for murder. He’s vigorously promoted clinical work as an important piece of law school education, helping found the Clinical Legal Education Association. And he’s become a go-to expert on mental health law, racking up numerous awards and serving on various boards and committees—including a commission that helped revise Illinois’s mental health code in the late 1980s and the nonprofit advocacy organization Mental Health America of Illinois, where he still chairs the policy committee.

“Mark’s legacy is that of a champion—someone who fought not only for his clients and others with mental illness, but for his students, colleagues, and for clinical legal education as whole,” said Dean Thomas J. Miles, the Clifton R. Musser Professor of Law and Economics. “He has left a lasting impression on many in our community, and we are thankful for his passion, dedication, and years of service.”

Added longtime colleague Randolph N. Stone: “Mark is recognized as certainly one of the leading mental health lawyers in Illinois. He is exceedingly well-respected and called upon by lawyers all over the state on issues related to mental health and mental illness, as well as the legal process when it comes to mental health issues.”

Stone—a retired clinical professor who led the Mandel Legal Aid Clinic between 1991 and 2001 and codirected the Law School’s Criminal and Juvenile Justice Project for decades—initially joined the clinic in 1977, a year before Heyrman. Their goals often overlapped as they each built projects serving vulnerable indigent populations, advocated for law school clinics, and incorporated social workers into their legal teams at a time when other schools remained resistant to the idea.

“I’ve known Mark forever,” Stone said. “He’s dedicated, and he’s a delight to work with. He’s got a great sense of humor, and what I’ve probably appreciated most is his commitment to social justice.”

A Zealous Advocate

That commitment has run like a thread through Heyrman’s work, fueled by a belief that people are more than their most heinous deeds, their mental and physical challenges, or the version of themselves they present the first time they meet someone. He believes that people are complicated and sometimes messy, but that it is important to look rather than look away.

Three years ago, Heyrman led seven students in seeking federal clemency for combat veterans who had been convicted of at least one homicide while deployed in either Afghanistan or Iraq. Each appeared to suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder, traumatic brain injury, or both—and some had committed particularly gruesome acts. None of the petitions succeeded—everyone involved knew it was a long shot—but the students learned what it meant to take the wide-angle view and to push themselves to comprehend the incomprehensible.

“They have all been able to . . . see the humanity in someone who did something bad,” Heyrman said as the students prepared to submit the petitions. “If you can do that with even one human being in your life, that’s pretty good. It widens your emotional horizon.”

The clinic’s litigation often focuses on the rights, treatment, and length of confinement of people who have been found not guilty by reason of insanity. Policy work has focused on a wide variety of issues, including the treatment of mentally ill people in prisons and jails, the rights and treatment of those confined to state mental health hospitals, and university policies for dealing with mentally ill students.

Alumni and students say Heyrman exudes a combination of toughness, kindness, and passion; they often describe a steely calm undergirded by fiery resolve.

“Mark was just such a zealous advocate, and he had so much enthusiasm for what we were doing,” said Amy Crawford, ’04, who joined the Mental Health Advocacy Project during her third year of law school. “He was always using his hands, raising his voice. But it wasn’t in an angry way; he was just animated and expressive, and you never doubted his passion or his commitment to the job or our clients. It was really fun to work with somebody like that.”

Crawford, who is the deputy chief of the Civil Actions Bureau in the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office, didn’t pursue mental health law after graduation. She’s worked as a litigation partner at Kirkland & Ellis, as the deputy director in the Cook County Department of Human Rights and Ethics, and once ran for alderman in Chicago’s 46th Ward. But the clinic sharpened her thinking and broadened her perspective in ways she appreciated.

“Mark was always ready to challenge you and whatever preconceived notions you might have had about a client or the strain of case law,” Crawford said. “I got exposure to a very specific area of the justice system that was unlike anything else I’ve had in my career, which has been really civil-oriented. It was an opportunity to gain a heightened sensitivity to the issues that people living with mental illness face.”

Angella Molvig, ’19, who joined the Mental Health Advocacy Project during her second year, has worked on both litigation and legislation. The proposed bill she’s helping draft would create a voluntary do-not-sell gun registry in Illinois, enabling people with mental illness to safeguard themselves from future impulses. Molvig, who worked in a domestic violence shelter before law school, is passionate about serving vulnerable groups and was eager for hands-on legal experience.

But she also appreciated the chance to see Heyrman in action. Once, as she waited in his office, he took a call from a former client who appeared to be struggling to understand his message. He repeated it, over and over, patiently and respectfully, and without “ever losing his cool,” Molvig said.

“He truly, truly cares about this population of people—a population that is largely ignored,” she added. “I mean, this is someone who went to the University of Chicago Law School and could have had any job he wanted—but Mark decided to stick around and be a clinical professor and not only help clients but help students, too. Working with him is an inspiration.”

A Champion of Clinical Legal Education

Heyrman, of course, hadn’t set out to be either a mental health lawyer or a law school professor.

He attended the University of Illinois at Chicago, graduating with honors with a degree in criminal justice administration in 1974, two years after completing his alternate service at Michael Reese during a break from his undergraduate studies. He enrolled in the Law School, thinking that he might pursue a career in criminal law, and joined the Mandel Legal Aid Clinic, a small but energetic operation led by Professor Gary Palm.

The clinic was a different place in the late 1970s: it offered students a valuable opportunity to gain hands-on experience, but it was largely extracurricular; the only academic credit came from a trial practice seminar taught by Palm and other clinic attorneys. The staff was small, composed of about half a dozen staff attorneys, most of whom were also clinical fellows; only Palm was a member of the faculty. Most of the clinic’s funding came from outside partners, and there were spots for only about 40 students. Everyone worked in cramped cinder block offices in the Law School’s basement.

“Gary was a big believer in specialization, except for the cases he handled himself. He did a hodgepodge of things, including some mental health cases,” Heyrman said. “When Gary learned that I had worked in a psychiatric hospital, he said, ‘Oh good, I’m assigning all the mentally ill clients to you.’”

Which was fine with Heyrman, though it didn’t alter his career ambitions. After graduation, he went to work as an assistant public defender in the Office of the State Appellate Defender of Illinois.

He was there for a year before Palm called with an idea.

The Law School’s clinic was expanding, and Palm and Charlotte Schuerman, the clinic social worker, had secured funding from the National Institute of Mental Health to create an interdisciplinary project that would bring students from the Law School and the University’s School of Social Service Administration together to handle mental health cases. Palm, remembering his former student’s mental health experience, wanted Heyrman to run the project.

And so, in 1978, Heyrman returned to the Law School basement, where he set about learning—all at once—how to be a teacher, a lawyer, a program director, and an advocate for the mentally ill.

“I probably wasn’t quite prepared to take this on, but I learned on the job,” Heyrman said. “At the beginning, Charlotte and I didn’t know what exactly a mental health project would do, but, you know, people with mental illnesses have all the legal problems that anyone else has—and then they have some special legal problems that only people with mental illness have, like being admitted [involuntarily] to hospitals. So over those first few years we experimented with doing a whole bunch of things to serve those needs.”

In those days, the cases covered an assortment of legal areas.

“We represented mentally ill moms who were threatened with the loss of their kids to DCFS,” Heyrman said. “We represented people who needed Social Security disability benefits due to mental illness. We represented mentally ill misdemeanants, meaning we did a little criminal law. We represented mentally ill clients in employment discrimination cases. At one point my students and I represented a group of people who were both mentally ill and deaf.”

There were advantages to learning on the job: Heyrman had a built-in empathy for his students as they navigated unfamiliar tasks, and he knew that steep learning curves could provide powerful opportunities to learn.

“I didn’t need to pretend not to know anything because I didn’t know anything,” he said. “I tried to be as honest as I could: ‘I’ve never done this before. We’re going to figure it out together. We’re going to figure out who to ask for help.’ And that’s what we did.”

By the end of his first decade, Heyrman was a recognized expert in the mental health law community. Illinois Governor Jim Thompson asked him to serve as the executive director of a commission aimed at studying, and ultimately helping to revise, the state’s mental health code. More than 30 of the group’s recommendations were enacted into law. In the coming years, Heyrman would begin doing policy work for Mental Health America of Illinois as well its national organization and a variety of other organizations and bar associations.

Heyrman also became a vocal proponent of clinical legal education. He’d seen what hands-on work meant to law students, how it expanded their thinking and helped them build skills they’d need as lawyers. He helped launch the Clinical Legal Education Association (CLEA) in 1992 and lobbied the American Bar Association to change accreditation rules to better incorporate clinical work into law school curricula across the country.

“At the time, clinics’ role in law schools was varied and, in many cases, tenuous or underdeveloped,” said University of Chicago Clinical Professor Jeff Leslie, the Law School’s Director of Clinical and Experiential Learning, Paul J. Tierney Director of the Housing Initiative, and Faculty Director of Curriculum. “CLEA’s policy advocacy played an important role in solidifying clinical education in law school curricula nationwide— promoting the ideas of a permanent clinical faculty, adequate resources for clinics, and academic freedom in clinic design and case selection. And CLEA’s trainings and workshops for new and experienced clinical teachers have consistently raised the level of clinical teaching and, thus, helped law schools to produce more practice-ready, reflective, and ethical legal practitioners. Mark is to be congratulated for his crucial role in creating an organization that continues to have an active and important role in advocating for clinics in legal academia.”

In 1996, almost two decades into Heyrman’s career, the Law School’s clinical program experienced its own leap forward. Arthur, ’39, and Esther Kane contributed a gift to build the Arthur Kane Center for Clinical Legal Education, a 10,000-square-foot structure that opened in October 1998.

For Heyrman and his colleagues it meant leaving the dark, cinder block offices and moving above ground into a sweeping space—one that included offices, meeting rooms, and a library.

A Thoughtful Teacher

Today, the Law School’s clinical program is a vibrant part of both the community and curriculum. It still operates out of the Kane Center, where Heyrman’s office, with its southern exposure windows, is often flooded with sunlight. On a top shelf above his desk, up near the ceiling, is a hard hat from the Kane Center groundbreaking more than 20 years ago.

Heyrman—who led the Law School’s clinical programs as an interim director between 2001 and 2003 and as faculty director between 2003 and 2007—meets often with students in this office, discussing research, strategy, and progress.

He cautions them to beware the pull of two emotions when approaching new cases: presumption and despair.

“By which I mean: presuming that things will be all right without our help and thinking that things are so bad you can’t do anything about them,” he said. “Both of those things are usually wrong.”

He’s thoughtful about which projects he takes on: he wants a good mix of both litigation and policy work, all offering opportunities for students to build skills that will serve them even if they choose an area other than mental health law. The cases can be uncomfortable—“Right now I have two different clients who beheaded someone, including one who beheaded his mother,” Heyrman said—and they’re often complicated.

“Our students are smart, so we tend to take on things that are more legally complex, that are more challenging, and that take advantage of the fact that we have very smart students who can muddle through very difficult problems,” he said.

Social worker Michelle Geller is often part of the Mental Health Advocacy Project’s legal team, along with students from the School of Social Service Administration, whom she supervises. (Geller, who joined the clinic in 1996, is also retiring this year.) Geller and the SSA students help bring a holistic approach to representation, offering insight into working with mentally ill clients and helping students protect themselves from the secondary trauma that can develop when one works closely with someone who has experienced or inflicted significant trauma.

Geller says both Heyrman and Stone saw the benefits of the holistic approach years ago—the Law School, in fact, was among the first to have a social worker on its clinical staff. Other law school clinics worried about reconciling a social worker’s mandated reporting requirements with attorney-client privilege. At the Law School, however, Geller and the SSA students are part of the legal team and are covered by the same privilege as the other members of the team.

Her work has given Geller a front-row seat to Heyrman’s teaching. She’s seen how rigorously he prepares his students, running through multiple drafts of documents and intensely mooting upcoming court appearances. He helps them refine and distill their points into clear arguments, enabling them to take the lead in a deposition or in court.

“First of all, there are few people in America who know more about mental health law than Mark, and he is able to impart that knowledge to students in a very effective way,” Geller said. “He helps them [to] bring out the best in their arguments, and to provide strong, effective advocacy.”

Michael Small, ’91, still remembers deposing an uncooperative witness as a second-year student. Heyrman was in the room supervising, but for the most part he hung back, giving Small the space to conduct the questioning.

The witness, however, was stubborn; he seemed determined to duck the question, no matter how Small asked it. Finally, Heyrman leaned halfway over the table, looked the man in the eye and said, slowly and quietly, “Answer the question.”

The witness answered.

“I remember how low-affect Mark was, how he dropped the volume of his voice but made clear to the witness that there was no escaping the question,” said Small, now a partner and bankruptcy attorney with Foley & Lardner. “I didn’t try and mimic it at the time; I didn’t yet have the gravitas. But I remember filing it away and thinking, ‘Someday I’m going to do that.’ And I have now, dozens of times.”

Heyrman, he said, taught him how to temper his behavior and tone to fit the needs of a particular situation. He also taught him that it was critical to show respect and to see past a client’s mental illness.

In another case, Small was advising a hospitalized client who was considering assigning his federal disability benefit to someone he referred to as his girlfriend. Small was convinced that the proposed beneficiary was taking advantage of the man, and he expressed his concerns to Heyrman.

“I was tremendously frustrated,” Small said. “I felt like I’d be helping the man make a terrible decision.”

Heyrman pushed Small to interrogate his own beliefs.

“He asked me, ‘Is [the client’s] mental illness impairing his ability to make this kind of judgment as the client—or do you simply feel bad for him and want to give him good advice about how to be a person in the world?’” Small said. “I learned that those are two different things.”

Heyrman’s hope is that his students take with them a broader perspective, an increased respect for people of all backgrounds, and a set of skills that will serve them in many areas of law.

For Molvig, who will work for a civil legal aid organization in the Detroit area after graduation, the experience has offered all of that. She’s grateful to have been among his final group of students.

“It was a great chance to develop practical skills— learning how to interact with clients and the supervisor and figuring out how to ask them right questions, which are all things you don’t learn that in the classroom,” Molvig said. “And it was great to learn from someone like Mark. He just gives it his all.”