Leader, Advisor, and Colleague to All

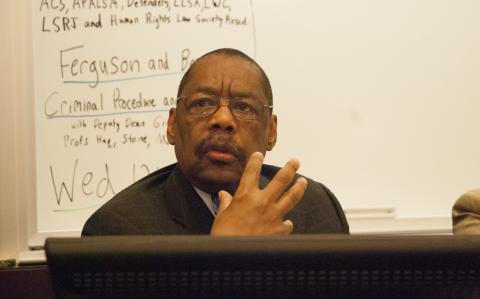

At a retirement party honoring Clinical Professor Randolph Stone last October, two of his longtime colleagues and friends, Clinical Professor Herschella Conyers and social worker Michelle Geller, took the microphone. Once the noise settled and they had everyone’s attention, Conyers cleared her throat.

“I would like to ask everyone who was a pupil of Randolph’s to step forward,” she said to the packed Green Lounge. After a moment of hesitation from the crowd, she added, “C’mon, you know who you are.”

A number of Stone’s former students stepped forward and joined Conyers and Geller near the podium.

“Now,” Conyers continued, “I would like to ask everyone who worked for Randolph to step forward.”

Again, a group of people stepped up.

Conyers went on to ask his colleagues at the Law School and at Chicago’s Police Accountability Task Force, where Stone recently led the Community & Police Relations Working Group, to move to the front of the room. After that, she asked anyone who had tried a case with him—or against him—to step forward. Soon, just about everyone at the party, an enormous crowd, faced the former public defender and longtime Law School clinician, whose more than four decades of work had earned him widespread respect as a leading advocate for children in the criminal justice system. For a few seconds, Stone stood still with his arm around his wife and looked at the group of people standing in front of him.

“On behalf of all these people,” Conyers said after letting him take it in, “thank you so much.”

***

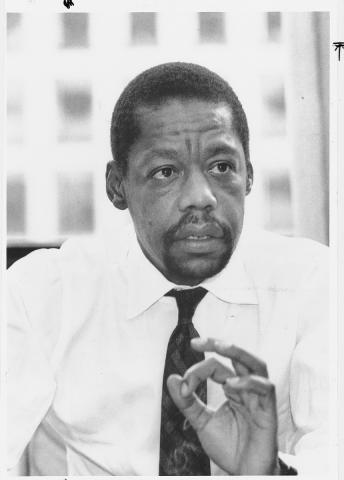

Stone’s commitment to social justice and serving those in need has shone through every stage of his career. As a public defender and, later, codirector of the Mandel Clinic’s Criminal and Juvenile Justice Project with Conyers, Stone offered legal representation to the most vulnerable populations. He has dedicated himself to bringing about policy reforms for a more equitable society—including his crucial role in abolishing mandatory juvenile life sentences without parole. As a law professor, Stone guided students through the intricacies of lawyering in the criminal justice system and instilled in them that same commitment to helping the underrepresented. And as director of the Edwin F. Mandel Legal Aid Clinic from 1991 to 2001, Stone amplified the clinical offerings, promoting a more varied clinical experience for students and developing initiatives that remain vital today.

After 31 years at the University of Chicago and so many invaluable contributions, it will be hard to imagine the clinic without his daily presence, said Director of Clinical and Experiential Learning Jeff Leslie.

“Randolph’s career has involved leadership positions in government and within the Law School’s clinic, where he served for many years as clinic director,” said Leslie. “It has involved courtroom victories with a lasting impact on how the criminal justice system treats young defendants. And it has involved blue-ribbon panels and prestigious awards almost too numerous to count.”

Even on their own, Stone’s accomplishments are remarkable, those who know him have said. What sets him apart, however, is the extent to which he is beloved by his students, clients, colleagues, and fellow attorneys. It’s the fact that despite his achievements and expertise, he remains humble, thoughtful, and devoted to listening to those around him, whether they are students offering a new perspective on a case or clients detailing their unique life experiences.

“Randolph has inspired generations of students through his example as a talented litigator, advocate, and educator, and through his commitment to justice and civil rights,” said Dean Thomas J. Miles, the Clifton R. Musser Professor of Law and Economics. “We are immensely grateful for his leadership in the Mandel Legal Aid Clinic and his tireless devotion to providing students with an exceptional clinical legal education. He is already missed.”

A Dedication to Serving the Underrepresented

Stone was born in Milwaukee, and after serving in the United States Army in Vietnam and earning a bachelor’s degree in political science with a concentration in economics, he went to law school with the intention of making a tangible contribution to society. Early on at the University of Wisconsin Law School, Stone developed an interest in criminal law.

“It just seemed like the perfect sort of fit intellectually,” Stone said. “I liked the challenging concepts, and I thought it was a great opportunity to help people make a change. And then if I was lucky, to change the course of human events by being involved in some serious policy reform issues.”

Shortly after receiving his JD in 1975, Stone was hired as a clinical fellow at the Law School, where he remembers working with a close-knit group of students in the school’s basement clinic offices. Stone would later work as a public defender in Washington, DC, and serve as the Public Defender of Cook County, where he was responsible for managing a $32 million budget and leading a 750-person law office. He would also teach at Chicago-Kent College of Law and Harvard Law School and start his own private practice law firm. In 1990, he returned to the Law School as a lecturer in law. Soon after, then-Dean Geoffrey R. Stone offered him a job as the director of the Edwin F. Mandel Legal Aid Clinic.

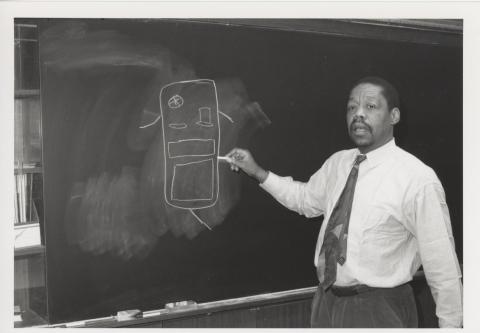

As director, Stone pushed the Mandel Clinic to grow in both concrete and less tangible ways. He oversaw the construction of the Arthur Kane Center for Clinical Legal Education, which moved the clinic from the basement to the state-of-the-art building it resides in today. He made an effort to broaden the variety of clinical experiences available to students, bringing the MacArthur Justice Center (which is now housed at Northwestern University) to the Law School, working with a group of students to start the Institute for Justice Clinic on Entrepreneurship, and introducing a new, hands-on trial advocacy course known as the Intensive Trial Practice Workshop. In 2000, he hired Clinical Professor Craig Futterman to start the Civil Rights and Police Accountability Project. Before that, one of Stone’s first major initiatives in the clinic was launching the Criminal and Juvenile Justice Project, which he codirected with Conyers until his retirement last fall.

“My initial goal was to try to create a project where students could be involved in state court criminal defense, so that they could see how the state system functioned and also focus on reform and policy to improve the system,” Stone said. “We quickly realized that the juvenile justice system was a fertile area for reform, given the tenor of the country and the way in which policy makers had begun to criminalize children and extend sentences for children.”

The End of Juvenile Life Sentences without Parole

In 1998, the Criminal and Juvenile Justice Project got involved in a case that would result in the end of mandatory juvenile life sentences without parole in Illinois. That year, Stone, Conyers, and students in the clinic represented a juvenile involved in a double murder outside of an apartment complex in Chicago. There were four defendants in the case. Two of them were lookouts who never fired any shots, and their client was one of those lookouts. Their client was acquitted by the jury, but when the other lookout, a 15-year-old boy, was found guilty, the trial judge appointed the Criminal and Juvenile Justice Project to represent him at the sentencing hearing. They were able to achieve a reduced sentence for him, persuading the judge that the automatic transfer to adult court and life sentence without parole was unconstitutional. But the state appealed the reduced sentence, which brought the issue to the Illinois State Supreme Court. To those in the Criminal and Juvenile Justice Project, the mandatory life sentence for a juvenile seemed excessive and unfair. They saw the case as an opportunity to make a difference and change the way juveniles experienced the criminal justice system.

“We started doing research about adolescent brain theory and international law,” Stone said. “And looking at international law, we learned that these life-without-parole sentences for juveniles were considered human rights violations in almost every other country in the world, except for the United States.”

Over the next few years, they worked with other legal clinics and coalitions throughout the state and the country to gather information. When the case appeared before the Illinois State Supreme Court in 2002, the Criminal and Juvenile Justice Project filed amicus brief representing two dozen organizations. The Court ultimately declared mandatory life sentences without parole for juveniles to be unconstitutional as applied to that case. Ten years later, in the United States Supreme Court case Miller v. Alabama, mandatory life without parole for those under 18 was ruled as broadly unconstitutional. In that case, Supreme Court justices heard some of the same arguments that the Criminal and Juvenile Justice Project had made in Illinois in 2002.

“There is still the possibility that someone, before his 18th birthday or her 18th birthday, could be sentenced to natural life,” Conyers said. “But the Supreme Court made it clear that they would consider that a rare event. I think, seriously, that the CJP and Randolph’s work in the abolition of mandatory life sentences for children is one of his crowning glories.”

The Supreme Court victory had ripple effects throughout the country, including new sentencing hearings for juveniles, now grown adults, who had previously been given life in prison. The Criminal and Juvenile Justice Project ended up representing some of those adults. At the same time, Stone would often remind his students that there are no small cases, only small lawyers.

“A lot of the so-called smaller cases that we’ve worked on—I still get chills when I think about how we saved someone from a long sentence or a felony conviction because of students who were willing to go the extra mile,” Stone said.

He recalled representing a misidentified client charged with armed robbery. The students used social media to help identify the real perpetrator of the crime and did extensive research on the use of questionable, suggestive techniques in the identification process, Stone said. They ended up winning the motion to suppress the identification.

“The judge ultimately dismissed the case,” Stone said. “And we ran into [the client’s] brother, who came into the office, and he said, ‘Every time I walk past the Law School, I just nod my head and say a prayer for the work that the students did on my brother’s case.’ Things like that stay with you.”

Social Justice in Clinical Legal Education

Having worked for years as a public defender, Stone had a deep understanding of police misconduct along with a resolve to address it. In 2000, he offered Craig Futterman the chance to develop and lead the Civil Rights and Police Accountability Project. It ended up being the first clinic of its kind in the nation, representing victims of police violence, working with community groups on policing-related class-action suits, and notably litigating the case that led to the release the Laquan McDonald dashcam video in 2016.

“The clinic that I started with him and under his leadership 18 years ago—it started as an idea and a thought,” Futterman said. “And that vision that he led and we shared didn’t exist in any law school anywhere around the nation. We could talk for hours and hours about all the cool things that we’ve done in my clinic, but none of those things would have happened but for Randolph Stone and but for his teaching, guiding, and mentorship throughout the time I’ve been here.”

For Futterman, the opportunity was twofold. It allowed him to run a project that addressed pressing issues in criminal justice reform—and it gave him a chance to work with the man who’d influenced his decision to go to law school. When Futterman was in college, his grandmother showed him an article about Stone being hired as the first black professor at the Law School in 30 years. Futterman was inspired by the article, and after some prodding by his grandmother, he called Stone to tell him how much it meant to him.

“This was before e-mail,” Futterman said. “And it wasn’t just that that he took the call or returned the call—it was also the kindness he showed me. Over the years he would mail an article or send a brief note of encouragement— small things that had a great impact. It starts with kindness, with his own authenticity and his commitment to justice that’s embodied in everything that he does.”

To better support students, clients, and clients’ families as they navigated the criminal justice system, Stone also made social work a vital component of clinical education at the Law School. He hired Michelle Geller in 1996 to head the Social Service Project. The project was designed to offer counseling to clients represented by clinic faculty and students and to foster collaboration with students from the University’s School of Social Service Administration. Though Geller had worked as a therapist in community health services previously, being part of a legal team was a new experience. Stone set an example for her, she said, that helped her win the respect of students and find her role within the team.

“I didn’t know what to do [when I started], but I watched this man—Randolph—who just lived the integrity, the hard work, the respect for your clients,” Geller said. “He didn’t just talk about it, he did it. It was helpful to develop a path for me because I knew if I could even be half of what he modeled, then the rest would be easier.”

Beloved by Students, Colleagues, and Clients

Over the course of his career, Stone has been recognized with countless prestigious awards and recognitions—in the last decade alone, he won the Heman Sweatt Award, honoring lawyers who exemplify the spirit of civil rights activist Heman Marion Sweatt; the University of Chicago Diversity Leadership Award; the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Illinois Association of Criminal Defense Attorneys; and the Safer Foundation’s annual Spirit of Safer Award, acknowledging significant contributions to criminal justice reform in the Chicago area. Stone has also offered his time and expertise by serving on numerous boards and committees, including Youth Advocate Programs, Inc., the Federal Defender Program, the American Bar Association’s Criminal Justice Section, the Illinois Department of Juvenile Justice, and Chicago’s Police Accountability Task Force, which was formed in the wake of the Laquan McDonald shooting to review the system of accountability and oversight in the Chicago Police Department.

The walls of the Kane Center are filled with plaques and commemorations recognizing Stone’s achievements, Leslie said. Given that history and a knowledge of Stone’s stature in the legal community, he added, it’s no wonder that students may feel intimidated when they first start working with him.

“What students quickly learn, however, is that, even with all the accolades, Randolph is humble, unassuming, and unpretentious,” Leslie said. “He is caring, kind, and devoted to his students’ learning and to their welfare. There is no clinical teacher who is more respected, or is more beloved.”

When Christopher Nathan, ’04, was a student, he joined the Criminal and Juvenile Justice Project because he wanted to help children and saw them as particularly vulnerable in the criminal justice system. Seeing how much Stone and Conyers loved the work influenced his decision to become a public defender, and one of the most salient lessons Nathan gained from Stone was to always respect and listen to his clients. Nathan remembers a whiteboard in Stone’s office being full of quotes, with some from clients and their families. One that Nathan still thinks about today read, “The public defender is trying to sell my son down the river.”

“To have that up there as a reminder, even after being a lawyer for 25, 30 years, that all of your clients’ and their relatives’ feelings are important and need to be attended to—I think that was the message,” said Nathan, who is currently a federal public defender in Iowa. “That even if a client offends you, even if your client’s parents offend you, you’ve still got a job to do.”

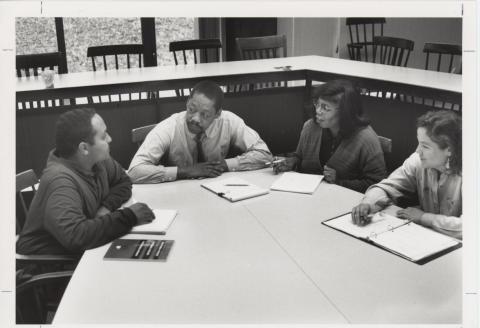

In the courtroom and in the classroom, Stone is known for being able to get to the bottom of the issue at hand, for seeming to always ask the perfect questions, and for his emphasis on thoughtful preparation. His motto, Conyers said, is “Plan. Do. Reflect,” and these words have become a staple of clinical education at the Law School.

“You see him, you hear him, you’re in a meeting with him and you know that this is not a person who is going to go off half-cocked,” Conyers said. “There’s an experience that I have had, and probably his students will confirm and say that they have had. We meet as teams, and when we plan our strategies and go around the room, everybody talks. But then Randolph says something and all of us just think, ‘Damn, why didn’t we think of that?’”

In addition to all of the skills and experience they take with them after working in the clinic, Stone hopes his students graduate with a dedication to serving those in need.

“I hope that they take with them a lifelong commitment to working with the poor, working with the disadvantaged, and working for social change,” Stone said. “They don’t have to be full-time civil rights lawyers or criminal defense lawyers. Even those that are in private practice in big firms or in corporations—I hope that they set aside some of their time to do pro bono work on issues of social justice.”

Noni Ellison, JD ’97, MBA ’97, said that Stone helped her understand as a second-year law student why all people, regardless of the crimes they’ve been accused of committing, have a fundamental right to legal representation. As a student in the Criminal and Juvenile Justice Project, Ellison found a mentor in Stone and remembers working with him on several legal matters, including getting parole for a client sentenced to 30 years to life in prison with the possibility of parole. Their client was involved in a murder, she said, though he hadn’t been the one to pull the trigger.

“Initially, I had a difficult time with it,” said Ellison, who is general counsel, chief compliance officer, and corporate secretary at Carestream. “But Randolph really helped to level set with me. He shared his perspective that everyone should have representation, and that the criminal justice system provides for an opportunity to rehabilitate. Randolph’s teachings have shaped my view of the criminal justice system from a defendant perspective, and my understanding that just because someone has made a mistake doesn’t mean that you should give up on them, and doesn’t mean that they shouldn’t have a second chance to be a productive citizen. Stone is primarily responsible for my ongoing commitment to reform the criminal justice system and to give back to the community in which I live.”

When Stone thinks about what he will miss most after retiring, the relationships with colleagues, clients, and students immediately come to mind. He recalled trying a case and not receiving the outcome he’d wanted—when he went to comfort the client, he said, the client ended up comforting him. He has learned a lot from his clients about their resilience and ability to overcome difficult circumstances, he said. He has also enjoyed collaborating with faculty in other clinical projects and working through issues with research faculty.

“Everything we did in our project was a result of collaboration, primarily with Professor Conyers and Michelle Geller and the students,” Stone said. “And when I say students, I mean the law students and the social work students. The collaboration, the collaborative aspect, is something I’ll miss because we always worked together as a team.”

In his retirement, Stone is looking forward to relaxing and destressing; to spending quality time with his wife, kids, and grandkids; and to having more time for reading, writing, and traveling. So far, he said, it has been wonderful.

Colleagues already miss Stone’s presence in the clinic, his leadership, his advice, and his generosity of spirit. Both Conyers and Futterman described the many times they had walked into Stone’s office, and that they could count on being able to talk through anything—not just strategy regarding a particular case, but pedagogy in general, the law, the news, their families. Leaving those conversations, Futterman said, he always felt supported, affirmed, and a little bit wiser.

“Even since he left, his presence is here,” Futterman said. “I feel it in what I do each and every day. I feel it in what I see my colleagues do. There are folks, regardless of titles, who are just leaders, and as long as I’ve been here, Randolph Stone has been a leader, trusted advisor, sounding board, and colleague to all.”