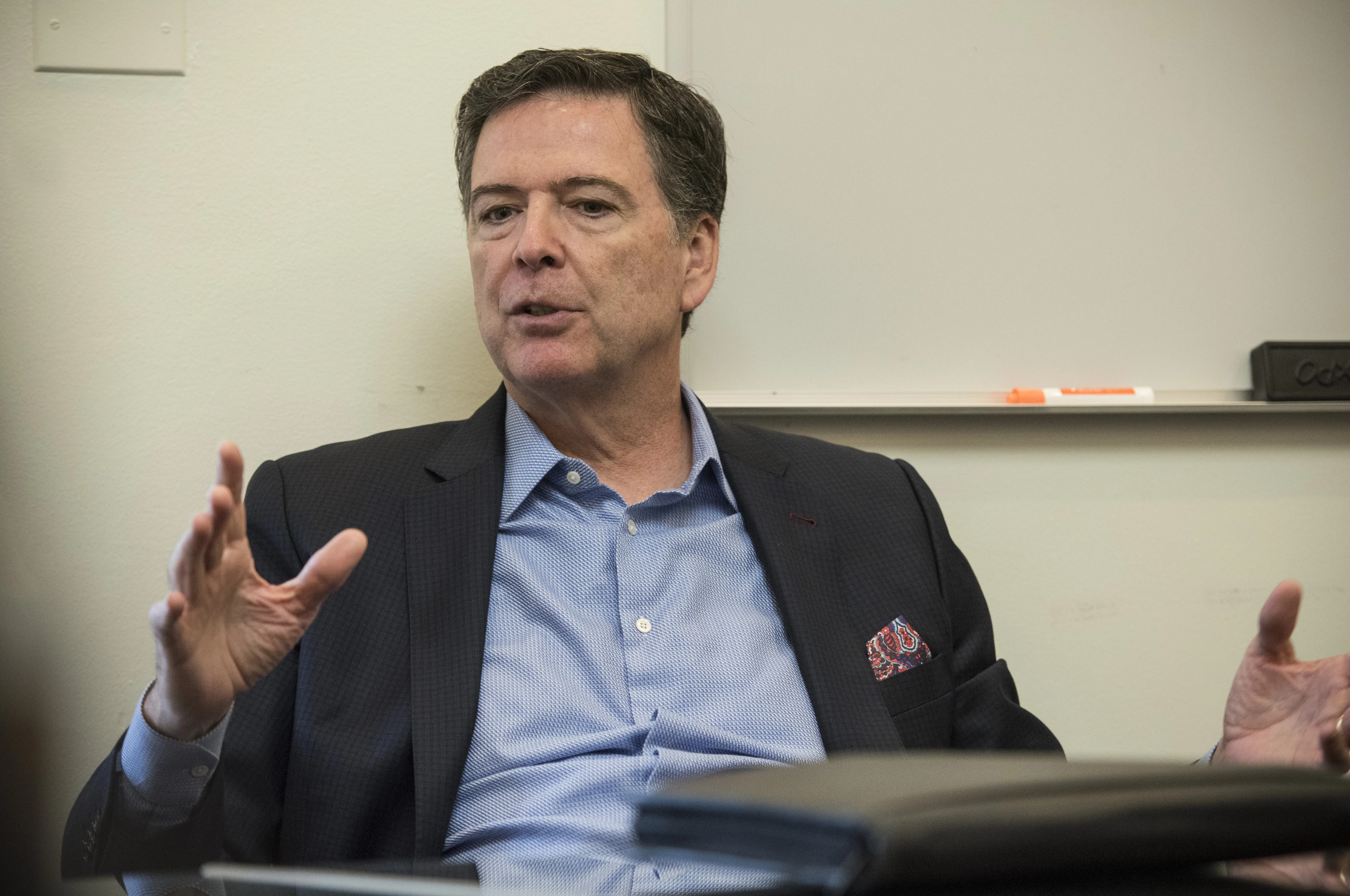

James Comey, '85, Discusses Truth, Transparency, and Trust at Law School Event

Truth is the center of the American justice system, but that isn’t enough to build public trust in those institutions, former FBI Director James Comey, ’85, told the University of Chicago Law School community during a virtual event on Monday. A strong system of justice, he said, also requires fairness and transparency.

That’s why it has always been essential for the US Department of Justice to maintain its independence within the executive branch, Comey told more than 130 students, faculty, and staff who attended the Zoom conversation led by Dean Thomas J. Miles, the Clifton R. Musser Professor of Law and Economics. Comey—who has criticized both former President Donald Trump and former Attorney General William Barr for eroding the public’s trust in the Justice Department—spent much of his career with the department and often speaks of it with admiration. Comey served as an assistant US attorney from from 1987 to 1993 and from 1996 to 2001 (he worked at a law firm in between), the US attorney for the Southern District of New York from January 2002 to December 2003, the US deputy attorney general from December 2003 to August 2005, and as the director of the FBI from 2013 until his dismissal by Trump in May 2017.

“The Justice Department is a key player in a system that has to be, both in reality and in perception, fair,” said Comey, whose second book, Saving Justice: Truth, Transparency, and Trust, was released in January. “It has to be nonpartisan, has to be devoted to finding facts based on just the facts and the law. The justice system only works if we trust it—if it is in reality a place where it doesn't matter what you look like, who you love, how you worship, how much money you have. We put a blindfold on our depictions of Lady Justice because we want to capture that idea that the playing field has to be level for everyone. Now, it never fully is, but [that needs to be] our aspiration for there to be justice.”

In the conversation with Miles, which included several questions submitted by students, Comey addressed a variety of topics. He talked about the things aspiring prosecutors and criminal defense lawyers should spend time learning (“anything having to do with the digital dust we are all leaving all over the world,” he said, noting that the criminal justice system increasingly grapples with issues related to online activity); his pandemic hobbies (yoga and self-taught piano lessons); and Twitter’s decision earlier this year to deplatform Trump (“I thought of … it as akin to turning off the natural gas supply to a building that's on fire … but I found it very, very sobering,” he said).

Comey—who has visited the Law School several times in recent years, delivering the 2019 Ulysses and Marguerite Schwartz Memorial Lecture, discussing race and policing during an October 2015 appearance, and offering remarks at the 2015 Diploma and Hooding Ceremony at Rockefeller Chapel—also returned to themes from those talks on Monday, often emphasizing the importance of transparency and trust.

During his visit to the Law School in 2019, Comey told students that Trump was “stress testing” the country, and, on Monday, he said he believed that America had passed that test with its norms not only intact but strengthened.

Comey also referenced the October 2015 talk in which he’d told a packed auditorium that he imagined law enforcement and the public, especially communities of color, as two lines that were arcing away from each other. “Each incident that involves real or perceived police misconduct drives one line this way. Each time an officer is attacked in the line of duty, it drives the other line this way,” he said in 2015. “I actually feel the lines continuing to arc away from each other, incident by incident, video by video, more and more quickly. And that’s a terrible place to be.”

On Monday, he said that one his “great regrets is that we have not found a way to arc the lines closer together.”

“I’m both more optimistic and sadder about the state of America and the relationship between the Black community and uniformed law enforcement,” he said, noting that he’s heartened that “we’re still talking about hard things” but worried that the conversations will lose steam or fail to fully address the underlying issues affecting American communities.

“There’s a lot that needs to be fixed in American law enforcement, but our problems go well beyond law enforcement,” he said. “This is also about healthcare and housing and employment and substance abuse and community institutions, and about things that are so hard that most of America chooses to either ignore [the conversation] entirely or to talk only about policing … which is not the root cause of our challenges in most of America's hard-hit neighborhoods.”

Comey said there are a number of issues related to police reform that need a “hard look,” including the doctrine of qualified immunity, which protects police officers from civil litigation in certain circumstances, as well as “the power of police unions to stifle accountability” and whether municipalities are investing enough in attracting and keeping well-qualified officers.

Transparency, he added, is essential to building public trust. He said prosecutors, for instance, need to “show their work” if they wish to overcome public doubt.

“After Michael Brown was killed in Ferguson, Missouri, the Department of Justice showed its work,” he said. “Even though it brought no charges, it showed it in great detail to the American people so they could understand why there wasn't a prosecutable criminal case in connection with the death of Michael Brown, but also why his death occurred in the context of a basically racist system in Ferguson, Missouri. That was really important to do, and I'm proud of the department for doing it.”

The Department of Justice, Comey said, serves a particularly important purpose in America.

“Our fellow alum, John Ashcroft [’67], when he was attorney general was fond of reminding people that [the Department of Justice] is the only cabinet department with a moral virtue in its name,” Comey said. “That should remind you of its unique role, which is to be a servant to something the American people need. It's not about advancing the president's political prospects. It's not about helping Republicans or Democrats. It's about being a steward of something that matters … a system that is designed to find a just result.”