Honest Talk on Aging and Retirement

Martha C. Nussbaum and Saul Levmore agree: people should talk more openly about growing old, and they should do a better job of planning ahead.

For the longtime University of Chicago Law School colleagues, whose divergent perspectives have fueled years of enthusiastic intellectual sparring, this accord offers the framework for a new book on aging in which their disagreements underscore a broader message about unchallenged stereotypes and one-dimensional narratives. After all, the lawyer-economist Levmore and philosopher Nussbaum see the world in very different ways—which is essential to this conversation, they note, because people grow old (and respond to growing old) in very different ways, too. It’s harder to make informed choices if one doesn’t have a chance to see varied paths, confront assumptions, or consider individual circumstances as part of a bigger picture.

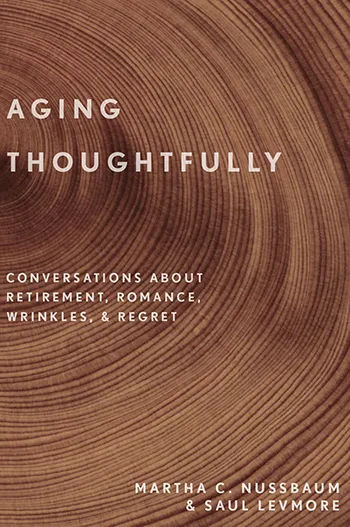

Aging Thoughtfully: Conversations about Retirement, Romance, Wrinkles, and Regret

In Aging Thoughtfully: Conversations about Retirement, Romance, Wrinkles, & Regret (Oxford University Press), Levmore, the William B. Graham Distinguished Service Professor of Law, and Nussbaum, the Ernst Freund Distinguished Service Professor of Law and Ethics, bring their distinctive personalities and viewpoints to bear on such topics as retirement policy, inheritance decisions, cosmetic surgery, post-middle-age romance, planned communities, charitable giving, friendship, and inequality. The book—which is modeled on Cicero’s On Aging, a 2,062-year-old work presented as a conversation between Cicero and his friend Atticus—is divided into eight themes, each with a pair of dueling essays. Here, we share excerpts of their chapter on retirement policy.

Must We Retire?

Saul Levmore

It is unlikely that I will be as good at my job at age seventy-five as I was at age fifty-five, and yet my employer might be stuck with me. An employer cannot require an employee to retire, even at a respectable age such as sixty-eight; mandating a retirement age as a condition of employment will be regarded as engaging in age discrimination, even if the employee was hired at a young age and even if the employer applies the policy evenhandedly to all workers as they reach the stated age.

The exceptions—including pilots, law enforcement officers, state court judges, law firm and investment bank partners (because they are not employees), and Catholic bishops—are few. Although a great majority of workers do retire by age sixty-eight, the fact that they need not do so surely causes employers to hesitate to hire middle-aged and older workers because they fear that these employees will not retire if and when their productivity begins to drop. Moreover, in many jobs, compensation rises with seniority even if productivity falls. Not only am I likely to be less useful to my employer at seventy-five than I was at fifty-five, but also my compensation at the older age will greatly exceed what I earned at fifty-five. Employers correctly fear that if they decrease or even flatten the salaries of aging employees, they will trigger age discrimination suits.

… I argue that, within limits, employers and employees should be able to contract as they like, even if this means that some workers will be required to retire at a specified age. If aging workers are sorry they entered into these contracts many years earlier, there will be other, younger workers who will be happy to apply for jobs that have finally opened up. Moreover, employers might be more willing to hire older job applicants if it is permissible to set their terms of employment. …

From an employer perspective, it has become difficult if not impossible to encourage retirement. Law seems to tolerate “golden handshakes,” or incentives offered at age sixty-two, say, to employees who agree to retire within two or three years. But it is widely thought that payments at age thirty, or upon hiring, in return for a worker’s agreement to retire at age sixty-five, would amount to unlawful discrimination, or simply be voided as a matter of contract law. It is noteworthy that sophisticated workers, including partners in law firms and consulting firms, who are not employees for the purposes of these laws, continue to contract for mandatory retirement. Their partnership agreements regularly provide for termination of the partnership interest by age sixty-five. Similarly, corporate officers and university officials are often, by private contract, required to step down at a specified age. In the latter case, they cannot be required to retire from their faculty positions, but the responsibility and extra compensation associated with an administrative position come to an end at age sixty-eight or at another specified point.

These private contracts are useful reminders of the desirable features of compulsory retirement. Of course, some workers are fantastic at their jobs well past any age we could specify. There are eighty-five-year-olds who are extraordinary managers, and requiring them to retire would impose serious private and social costs. Some law firms, for example, go to great lengths to keep these few marvels on the job. But there are also many workplaces in which it is awkward or even harmful to suggest to someone that he or she ought to retire, and if workers can continue forever, then more such conversations are required. Age discrimination law requires that the firm show that the worker is no longer fit for the job, or has misbehaved, and this can be difficult, expensive, and humiliating. It is easy to see why some employers might prefer to have a rule requiring retirement at a specified age, even though the rule comes with a cost to some employees as well as to the employer. Contractual retirement of this sort also makes room for new employees and new ideas. Nothing stops the retiree from opening a business or looking for work elsewhere, because nothing requires all employers to mandate retirement; the idea is that compulsory retirement would be of the permissive, contractual, and agreeable kind.

It is plausible that such contractually forced retirement would reduce rather than encourage any stigma attached to aging. If everyone in a workplace must retire at age seventy, there is the danger that persons above seventy will be seen as over the hill, even away from the workplace. But there is the alternative and rosier possibility that retirees will be understood as having agreed to a scheme in which they benefited from the retirement of their predecessors, and they now agree to make room for their successors. A rule requiring retirement can be less of a taint than a few drawn-out and uncomfortable processes in which ineffective senior workers are shown to be liabilities and then pushed out. Where there is no mandatory retirement, older employees might be seen as the least competent because the employer cannot easily reduce their wages or let them go. If this seems far-fetched, I invite observation and introspection. Which teller do you approach at a bank? In my experience, tellers in their thirties and forties appear to be the favorites; they are sufficiently experienced to be quick and to recognize regular customers, but not so experienced as to be, well, slow. It may well be that a seventy-five-year-old teller is as proficient, but from the employer’s point of view that older teller has received wage increases over the years and is surely not twice as productive as the forty-year-old.

It is likely that if law were (once again) to allow employment contracts to specify a retirement age, employers might find middle-aged and even older employees more attractive. …

[M]any employers have developed retirement incentives that are accepted by a significant percentage of eligible employees. An employer might have a standing offer that any employee at age sixty-five can agree to retire at age sixty-eight and, in return, receive a payment equal to one year’s salary or even more. If these plans remain in effect for many years then, eventually, the employees who accept or reject these payments will no longer be those who received a windfall from the elimination of compulsory retirement. It is plausible, therefore, that no great change in law is needed from the employer’s perspective. Employers will simply have shifted from at-will employment contracts (allowing them to dismiss workers without fear of lawsuits) to mandatory retirement to defined benefit plans and now to severance contracts. A less optimistic story is that employers have learned to be very careful before hiring employees who can overstay their welcome, with the threat of lawsuits in the air. I will not overclaim and say that the surge of part-time workers comes as much from the inability to contract about retirement as it does from the cost of healthcare and other benefits, but there is probably some cause-and-effect relationship between the end of compulsory retirement and the bringing on of more part-time workers. In universities the substitution is dramatic. University expansion has come through hiring adjuncts rather than full-time faculty; the adjunct faculty scramble for positions and pay, while full-time, tenured professors, now enriched by the option of staying on as long as they please with almost zero risk of removal for cause, comprise less than half the teaching force and a yet smaller fraction of new appointments.

If the ban on mandatory retirement contracts is costly to employers, and therefore to many employees, why do we not see pressure to change the law? Law might, for example, allow private contracts with set retirement ages. Current employees would oppose this change, and it would likely be necessary to protect them against the possibility that an employer would simply terminate them and then offer to rehire them under the terms newly permitted by law. Moreover, employees might fear that they will be terminated in order to make room for new employees who could be signed to these new, mandatory retirement contracts. But if set retirement terms are only permitted in new contracts with new employees, then there will be very little political pressure to pass such laws. Employers will have little to gain because they will not enjoy the benefits of the new law for many years; they must “pay” for law now but profit from it far in the future—assuming the law does not change back meanwhile. …

[O]urs is an aging population and the center of political gravity is likely to oppose anything that can be seen as limiting the options of senior citizens. This may already be evident from the inability of state and local governments to reach negotiated, political solutions to their underfunded pension plan problems. If the ban on mandatory retirement is ever to end, reform will need to come in steps that anticipate the objections of powerful groups.

One way to reduce opposition to legal reforms is to delay change, pushing the burden of change into the future. A proposal made in 2017 to allow retirement ages in employment contracts beginning in 2037 would have a decent chance of passing because most of the apparent losers are unknown and certainly not politically organized. … Another strategy would be for employers to announce that compensation will follow an inverse U. … It is not clear that courts would allow this scheme, and inasmuch as it would almost surely be limited to new employees, so that any savings would come about after decades, such a plan is probably not worth the effort it would require to enact.

A better strategy, I think, would be for law to promise that no age discrimination suit could be brought by anyone over a specified age, such as sixty-eight. Social Security and other retirement plans would provide income for retirees, and it would be a part of the strong statutory default for retirement. Some employers might then offer employment contracts that reduced compensation by 5 percent every year after age sixty-eight. (Automatic decreases prior to that age would need to survive age discrimination suits.) Other employers might simply structure contracts so that employment ceased at age sixty-eight, perhaps the same age that maximum Social Security benefits became available, but the employer and employee could choose to negotiate a new contract for work beyond that age, and at any wage they agreed upon …

Another idea for easing back into a legal regime that permits retirement ages to be set by contract is to begin by taxing affluent older workers. Most voters are worried about the solvency of the Social Security system. They will also be sympathetic to seniors who have supported family members and now need to work for their own, often postponed, retirement. These workers may have relied on the absence of mandatory retirement, or simply gone through tough times. Consider, however, a proposal to limit full benefits to retirees who leave the workplace by the median retirement age, unless their annual income is under $75,000 a year after that age. Imagine that Social Security benefits are capped at $30,000 per year, and that this amount is available to someone who retires at the prevailing median retirement age of sixty-two. Under this proposal, the cap would be $27,000 for one who retired by age sixty-three, $24,000 at age sixty-four, and so forth until an affluent person (with more than $75,000 in annual income) who retired beyond age seventy-two would simply receive no Social Security benefits at all. … Most present and future Social Security recipients should be expected to favor this plan because it conserves resources for a troubled system at the expense of a fairly small group. The losers are very affluent older workers—most of whom began their careers expecting a mandatory retirement age, and then received a windfall. As for younger citizens, those who expect to be well compensated might come to resent Social Security, because they might pay in to the system and then receive low or zero benefits. But this result will only be true for workers who choose to retire later than the median retirement age. The more likely impact, especially with respect to workers who earn between $75,000 and $150,000, is to encourage early or typical retirement in order to avoid the implicit and substantial tax on work done after that age …

The larger point here is that the ban on mandatory retirement is just the sort of thing that an interest-group-driven democracy is likely to create and then find very difficult to undo. Rules against age discrimination are appealing, and many voters will think they stand to gain from the antidiscrimination law. … Any assault against the ban on mandatory retirement, or any attempt to make it easier for employers to dismiss underachieving employees (protected by age discrimination law), will arouse the fierce opposition of this powerful group. Younger workers are unlikely to support change with matching intensity because members of this potential interest group do not really know whether they will individually gain from legal change. An identifiable group of potential losers will normally be much more active and successful in the political arena than will a group of dispersed, unidentifiable, potential winners. It is unlikely that younger workers and voters can undo the ban on compulsory retirement—even where employees voluntarily agree to such terms. If change comes, it will be because of evidence that businesses are migrating to other countries with greater freedom of contract.

No End in Sight

Martha C. Nussbaum

Like all American academics of my generation, I have been rescued from a horrible fate by the sheer accident of time. At sixty-nine, I am still happily teaching and writing, with no plan for retirement, because the United States has done away with compulsory retirement. Luckily for me, too, the law changed long enough ago that I never even had to anticipate compulsory retirement or to think of myself as a person who would be on the shelf at sixty-five, whether I liked it or not.

Moreover, given that philosophy is a cheerfully long-lived profession, I have been able, from the angle of my profession as well, to anticipate happy productivity in my “later years.” Elsewhere, following Cicero, I discuss the longevity, and the late-age productivity, of ancient Greek and Roman philosophers, and numerous leading philosophers of more recent date. My cohort grew up on such stories. Examples closer to home also nourished our hopes: the great John Rawls published only a couple of articles before the age of fifty, when A Theory of Justice appeared. And Hilary Putnam, who died in 2016, just shy of his ninetieth birthday, never stopped changing his mind and generating new ideas. At his eighty-fifth birthday conference, when young philosophers delivered papers for three days on every aspect of his work, from mathematical logic to the philosophy of religion, he bounced up gleefully to reply to each, and almost always said something more interesting than the speaker.

It’s no accident, then, that it seems weird and horrible to me to see members of my age cohort in philosophy turned out to pasture, just because they happen to be employed in Europe or Asia, even though they are a few years younger than I am. Some have been dismissed not only from department and office but also from university housing, forced therefore to relocate, sometimes to distant isolating suburbs, too far away to interact regularly with scholarly pals or graduate students, or for any of them to see much of their former colleagues. This seems all wrong to me, and I feel so happy that I can go on until summoned by fate—or until I want to do something different.

My romance with work is part of my romantic and idealistic take on life—to which Saul, characteristically, delivers a contrarian jolt of hardheaded realism. So now I have to stop focusing on my own emotions (!) and come up with some arguments. Fortunately, I am not at a loss. (If this were email, a smiley face would appear at this point.)

A caveat: I’m talking mainly about work that the worker experiences as meaningful, not about mind-numbingly repetitive white-collar work, and certainly not about hard physical labor. For those careers, retirement is already a popular choice in the United States, and, under the right circumstances, compulsory retirement of the sort Saul envisages might do just fine. We must carefully distinguish between the age at which retirement is permitted and an age at which it is required. But notice that early retirement from boring jobs now often leads to the choice of a second career, often with more meaning attached. Recently both the rabbi and the cantor in my temple were second-career women. If those doors should close through compulsory retirement of some type, meaningful second-career options will be limited to volunteer work, available only to those with sufficient income.

Healthcare, Equality, Adaptive Preferences

But let’s think further. And let’s start with the best case of compulsory retirement I have encountered, in the academic world: compulsory retirement in Finland. I’ve spent a lot of time there, and by now many of my good friends are compulsory retirees, the age being sixty-five. (Retirement is compulsory in all walks of life; I focus on the academy for now, since I know that area best.) The climate is salubrious, and my retired friends are for the most part healthy and potentially productive. But they can’t teach or go to the office. Still, nobody is complaining. To my knowledge there is no lobby group pressing for an end to the policy. My personal acquaintances by and large express satisfaction. Indeed, Finnish norms dictate no complaint, even to colleagues, even in the direst matters. The right way to face terminal illness is thought to be silence until a few days before the end. So my friends would think it bad form to complain or even to start an interest-group movement. What are their underlying attitudes? Social norms kick in there too, I believe. I probe and ask and observe, and I really do believe that people feel satisfied. Or if they feel pangs of discontent, they also feel guilty about those feelings.

So why are philosophers in Finland apparently satisfied with something Americans by and large repudiate and disdain? Social norms and expectations, I’ll argue, are the largest factor. But there are two other factors I want to explore first.

The first is health insurance. Finland has a generous and high-quality comprehensive national health insurance scheme, the same for all, and it supports a high quality of both medical and nursing care (including in-home care) whether or not one is working. People grow up used to this, so they don’t get anxious about future needs for care. US elder care under Medicare and Medicaid lacks some features of the Finnish system, and aging people correspondingly feel less secure. Recently, as the Finnish system starts to be cut, and nursing care is only unevenly available (see my chapter on inequality), Finns are becoming much more worried about retirement. But they are still doing relatively well in world terms. Still, security about healthcare is not the primary issue for the group I’m talking about, the people who work because their work is meaningful to them.

More important, there’s an equality issue. Finns do not regard compulsory retirement as a disparagement, because (they say) everyone is treated alike. There is no message of ranking. It’s a simple calendar age, and it is imposed without exception. It does not track antecedent inequalities of status. So you don’t have to hang your head in shame. With Saul’s scheme, appealing in many ways though it is, there is no equal status, and those whose contracts force retirement will feel they have to hang their heads by comparison to those whose power was great enough to negotiate a desirable long-term contract ex ante. My guess is that if Americans reject the Finnish system they would be even more dissatisfied with Saul’s system, because it causes invidious comparisons.

Still, I would like to ask my Finnish friends why any rational person thinks it is good “equality” when all aging people are treated equally badly. Surely we would not accept as a good type of equality the denial to all citizens of religious liberty or the freedom of speech. I shall return to that point in my next section.

If people were forced to retire when, and only when, they were true slackers, they would feel more stigmatized than they might in Saul’s system, but at least, in their hearts, they would see a basis for the differential treatment. But the inequality problem in any academic scheme of negotiated retirement is not likely to be as rational as that, or based on sound academic values. We’ve been there before. In the old days before the end of compulsory retirement in US universities, judgments about who should retire were made in accordance with all sorts of irrelevant factors, such as fads and social prejudices. In the Harvard of my graduate school days, when the university was permitted to decree that some retired at sixty-five, some at sixty-eight, and some at seventy, choices were conspicuously not made in accordance with academic productivity or beneficial contributions to the academic community. They were more often made in keeping with fads, alumni connections, and even baneful prejudices such as class and (I am sadly convinced) anti-Semitism. (They were not based on gender simply because there were no tenured women.) In short, unequal treatment, problematic in general, is especially problematic when it gives incentives to institutions to distort the academic enterprise in ways that track existing hierarchies that are peripheral to the academic mission.

Would Saul’s plan have less distortion of that sort? To some extent it would, since people would negotiate ex ante, not when they were close to retirement age. But once inequality is built in, I surely don’t trust institutions to make even ex ante judgments on the basis of sound academic values. …

Unfortunately, the research we have until now does not yet enable us to study the interaction between social stigma and compulsory retirement. One would predict that having no retirement age would counterbalance, to some degree, the demeaning messages that are all around us. At least we’re now getting mixed messages, not uniformly negative messages. But since the work mingles US and British data, and since Britain is itself mixed, having compulsory retirement in some fields and some places and not others, it is hard to study these interactions. What worries me about Finland is that when you are told from the cradle that productive work ends at sixty-five, you will believe it, and you will define your possibilities and projects around this. You will expect to go on the shelf and others will expect you to be on the shelf. Not to mention the absence of things like office space and research support, you won’t get the invitations you are used to or the respectful treatment from younger colleagues.

And you will not protest, because, in short order, you will come to see yourself as useless. One of my retired Finnish friends was happy initially, finding that she had more time to spend with her husband (also forced into retirement) and more time for the gym. Two years on, however, she is ashamed to come to dinners after a visiting lecture by me, her friend. She feels she does not belong, and that she ought to say no, even when I invite her. This is a terrible form of psychological tyranny.

The emeritus status might conceivably be redesigned to be less stigmatizing, as when, in our law school, retired professors keep an office, are welcome at workshops and roundtable lunches, and teach if they want to. But nobody has thought this through in a convincing way across the wide span of the professions.

Now of course Saul’s plan allows for a lot more individual flexibility than the Finnish plan. The very features that make it do worse on the equality problem make it do better on the adaptive preference parameter. No specific age is the age at which one is on the shelf, and people will see all around them productive people in their later years, so they won’t be forced to see themselves in the light of a stigmatizing social norm. But I still worry. The United States in particular is so full of youth-worship that it is only the total removal of compulsory retirement that allows so many of us to resist society’s psychological pressure, in our thought about ourselves and our worth, and to continue to lead productive, respected lives, in which we do not define our worth by a calendar number. …

The Equal Protection of Law

The greatest advantage of ending compulsory retirement is the one [John Stuart] Mill claimed for ending discrimination against women: namely, the advantage of basing central social institutions “on justice rather than injustice.” …

Mill emphasized that all forms of domination seem “natural” to those who exercise them. Feudalism made elites think that serfs were by nature a different type of human being. It took revolution to change consciousness. Racial discrimination and discrimination against women have been similarly rationalized by a belief, no doubt sincere, that this discrimination was based upon “nature.” Discrimination against people with disabilities was not recognized as the social evil it is because for a long time so-called normal people just thought it was natural that society catered to their needs (including their bodily limitations) and kept “the handicapped” outside. Discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation was wrongly rationalized as acceptable because gays and lesbians were acting “against nature.” Age is the next frontier and, so far, most modern societies think that unequal treatment on the basis of age is not really discrimination, because of “nature.” They are wrong. Age discrimination, of which compulsory retirement is a central form, is based on social stereotypes, not on any rational principle. And it is just as morally heinous as all the others.

We must now face the inevitable objection that ending compulsory retirement is simply too costly. In addition to observing that keeping people productive rather than supporting them through Social Security might be thought to be a savings, not a cost, we should reply that when it is a matter of extending to a group equal respect and the equal protection of the laws, expense cuts no legal ice. When that same argument was made against including children with disabilities in integrated public school classrooms, the courts said that the financial shortfall of the school district that was griping about including “extra” children must not be permitted to weigh more heavily on an already disadvantaged group than on the majority. This was the correct response.

And just imagine the response if people were to say, let’s exclude women and minorities from the workplace, because there are not enough jobs—or, more pointedly, because “they” are taking “our” jobs. People of reason would rise up, objecting that the full inclusion of all qualified workers on a basis of equality is an urgent issue of justice. Not all people are people of reason, and this so-called argument has recently been a major political force in the United States. But fear of popular anger should not stop us from doing what is just, any more than the huge violence of the civil rights era stopped the struggle for racial equality. …

The United States has done well to reject compulsory retirement and to adopt laws against age discrimination. All countries ought to follow this lead. Indeed it is astonishing how powerful law has been. Our country is perhaps even more youth-focused than most, and yet aging workers are treated much more justly. Such would not be the case, were law not firm and unequivocal. (And law would not have become firm and unequivocal but for the work of lobbying groups, above all the AARP.) There is a lot of work yet to be done, since age discrimination persists, albeit illegally. But I’m happy that we aging professors have no end in sight—apart from the one that awaits us all. And having some useful work is a fine way to avoid useless brooding about that one.

* * *

Adapted from AGING THOUGHTFULLY: Conversations about Retirement, Romance, Wrinkles, and Regret by Martha C. Nussbaum and Saul Levmore. Copyright © 2017 by Martha C. Nussbaum and Saul Levmore and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.