Through the Eyes of a Nobel Laureate’s Wife

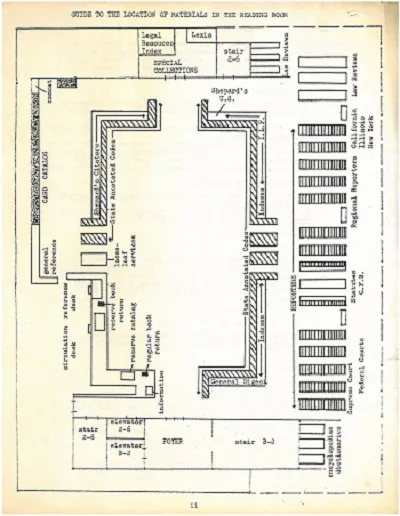

Throwback is an occasional series offering glimpses into the Law School’s rich history. All photos in this installment are part of the Ronald H. Coase Papers, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

Ronald H. Coase and his wife, Marian, had just buckled themselves into their seats on the last leg of a journey from Chicago to Stockholm when an unusually loud and clear voice came over the in-cabin announcement system, jolting them to attention.

It was early December 1991, and their flights so far had been mercifully calm and relaxed. Less than two months earlier, the couple had been visiting Tunisia when a Reuters reporter approached them and became the first to tell the 80-year-old economist—a University of Chicago Law School professor well regarded as a founder and leader in the field of law and economics—that he’d won the Alfred Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. (“I didn’t know a thing,” Coase later recounted. “I’m really pretty fortunate to be in a place where it’s so difficult to reach me. It’s a good place to learn about it—a place so ancient.”)

Now, as the plane prepared for takeoff, someone on the cabin crew wanted everyone to know that a new Nobel laureate was on board—and that champagne would be served in his honor.

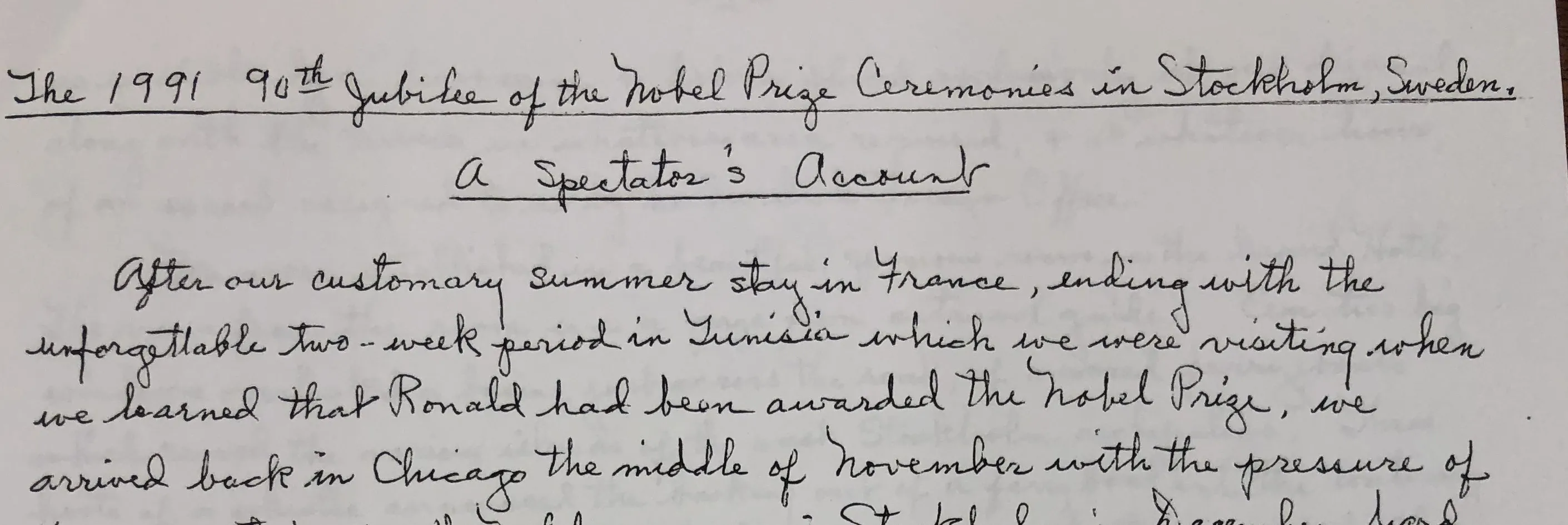

“And it was, immediately, the trays of glasses having already been prepared,” Marian recalled in a 15-and-a-half page handwritten account of their visit to Sweden for the Nobel Prize ceremonies. “We were grateful that there was no spotlight on the plane to shine on us.”

So began the trip of a lifetime: one documented not just in news stories extolling Coase’s work on transaction costs and the nature of firms—but one chronicled in about a dozen Nobel-focused folders that are part of Ronald Coase Papers, which became publicly available earlier this year at the at University of Chicago Library’s Special Collections Research Center. The collection, a 186-box treasure trove of research files, drafts, lectures, personal and professional correspondence, notes, reports, photographs, clippings, artifacts, and more, offers insight into both the mind and the man, a Law School legend who died in 2013 at age 102. Marian Coase died in 2012.

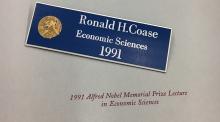

The materials documenting Coase’s 1991 Nobel Prize are just a small part of the 112.5-linear-feet collection. But they paint a picture of an extraordinary experience that only 923 global leaders in chemistry, physics, medicine, literature, economics, and peace have shared. When Coase won the economics prize—which wasn’t established until 1969 and is technically the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel—it was a distinction he shared with only 30 others, nearly half of them associated with the University of Chicago.

This year, University of Chicago Professor Richard H. Thaler, the Charles R. Walgreen Distinguished Service Professor of Behavioral Science and Economics at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, was honored “for his contributions to behavioural economics”—becoming the 49th Nobel laureate in economics, and the 29th associated with the University of Chicago. Although Coase won his prize more than a quarter century ago—in a year of particularly elaborate festivities designed to mark the Nobel Prizes’ 90th anniversary—the artifacts in the Coase Papers offer a hint of what Thaler, and his wife, might expect when they travel to Sweden in December for the awards banquet and other events.

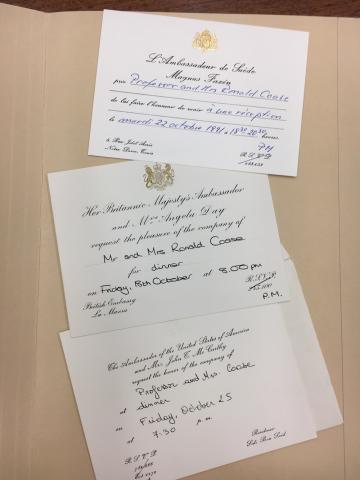

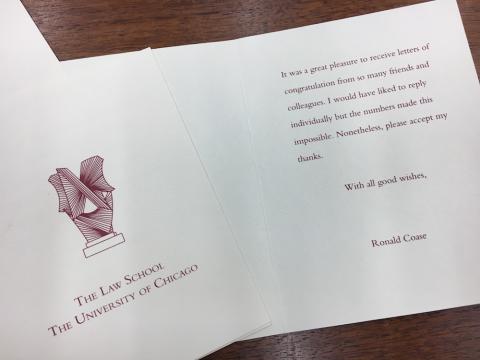

The Coase Papers include dinner invitations from ambassadors, printed University of Chicago Law School thank you notes (“I would have liked to reply individually but the numbers made this impossible”), news clippings, congratulatory notes, laureate information, letters nominating Coase for the Nobel in the 1970s and 1980s, and an official program emblazoned with a gold Nobel Prize seal. And then there’s Marian Coase’s neatly written account, assigned to its own folder. It is relayed with an attention to detail, as if she hoped to keep the particulars of their visit from being lost to history. She describes moments of splendor, from listening to Georg Solti conduct Johannes Brahms' Symphony No. 1 at Stockholm Concert Hall (“Fortunately, we sat near enough to hear the machinery at work … I understood, from the sound of the first chord, why Solti … commands such high praise. It wasn’t just satisfying Brahms, it was great Brahms”) to dining at the Royal Palace at a dinner given by the King and Queen of Sweden.

“The meal was chosen with the skillful restraint of a grand gourmet who was, I was informed, the King himself,” she wrote. “He was also responsible for hunting the deer whose meat, exceptional in both flavor & in texture, was the star offering of the main course.”

Marian marvels again and again at the efficiency, organization, and planning expertise displayed by the Nobel Foundation, and she tells of the “intricate maze of events” that were at once spectacular and exhausting.

The couple, who had been traveling until mid-November that year, had only two and a half weeks in Chicago before leaving for Stockholm. Preparations had been intense, with Ronald fielding congratulatory notes and interview requests while writing his 45-minute Nobel lecture and three-minute banquet remarks and Marian assembling appropriate “special events” wardrobes, something she’d never troubled about in previous travels. Garment alterations stretched to the last minute; in fact, she’d set down her needle and thread “only moments before rushing off to O’Hare Airport.”

In addition to the time pressure, there had been the sudden shock of sad news: Ronald Coase’s friend and colleague George Stigler, the 1982 Nobel laureate in economics and a member of the University’s economics faculty, had died suddenly on December 1, just days before Coase left for Stockholm. The grieving Coase offered a tribute as a prologue to his prize lecture, Marian wrote, adding that his words “seemed to lead his friend into the auditorium to acknowledge all the allusions to him in the Lecture.” Afterward, numerous people came by to tell Ronald that he’d given a fine eulogy. (Stigler actually formulated and named the Coase Theorem based on an argument Coase made in his well-known 1960 paper on transaction costs, “The Problem of Social Cost.” In his lecture, Coase made this distinction.)

The action-packed week hit its crescendo the next day when 1,300 people gathered for the much-anticipated Nobel Prize ceremony and banquet.

“One was warned not to make too many demands on one’s energy the day before as the day itself would be long & arduous & it all was going to be televised,” Marian wrote. “Everyone was counted on to be punctual and not to make mistakes. The Laureates were taken to the auditorium & rehearsed—& no doubt the King and Queen went through their paces as well.”

The demanding pace ultimately took its toll, and Coase fell ill with a cold and fever on the flight home. On Christmas Day, Ronald and Marian Coase finally “abandoned ourselves to sleep & awoke, unbelievably, 18 hours later,” Marian reported. “It was no longer Christmas but late in the morning of the 26th.”

Despite the physical impact, the week had included various thrilling extras. The day after the banquet, Ronald, who had explored the economics of lighthouse management in some of his work, was taken for a private visit to the Swedish Lighthouse Authority. Two days before the banquet at Stockholm City Hall, the Coases were able to make a private visit to the building to admire the “bold design that had made a strong impression on us when we saw it forty-five years ago,” Marian wrote. And on the way back to the States, they had a nice stop in Paris.

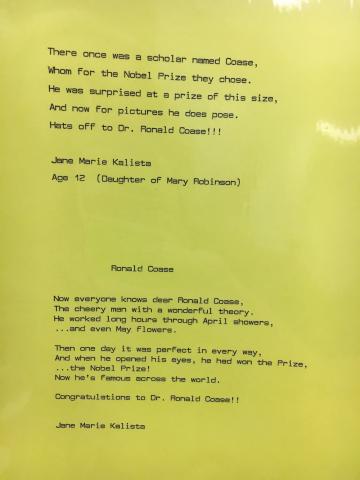

Afterward, as Ronald settled into life as a Nobel laureate, someone compiled an album, pages of which are preserved in the collection. Affixed to the sticky pages with clear plastic overlay are yellowing news clippings, including a Chicago Tribune story featuring a photo of Marian and Ronald locked in a tender kiss, and a hand-drawn note of congratulations with multiple signatures. There’s a picture, too, of a blue ribbon labeled “Nobel Prize Economics” drawn in marker by a 12-year-old who appears to be a family friend.

The same child wrote him a poem that also relays the magnitude of the experience:

There once was a scholar named Coase,

Whom for the Nobel Prize they chose.

He was surprised at a prize of this size,

And now for pictures he does pose.

Hats off to Dr. Ronald Coase!

![The first page of Marian Coase's account. Source: Coase, Ronald H. Papers, [Box 1, Folder 22], SCRC, UChicago Library.](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/marian%20account%20p1%20scaled.jpeg?itok=w_ELgYIt)