Finding Their Voices

Standing before a group of about 45 law students in the Weymouth Kirkland Courtroom, Sharon Fairley, ’06, began her closing argument as the prosecuting attorney in a double homicide case. The day before, students had learned the essentials of putting together a closing argument. Today, they would get to see an accomplished attorney demonstrate one in real time.

“This case reminds me of an old Bonnie Raitt song,” Fairley said. “‘I Can’t Make You Love Me If You Don’t.’” She paused before repeating the title once more: “I can’t make you love me, if you don’t.”

Fairley’s tone was calm and measured. The song title glowed behind her on an enormous projection screen facing the students, who appeared completely absorbed by Fairley’s argument. As she told the story of the case, she brought up potential questions and then waited a beat before answering them. All of it reflected a style Fairley had developed after years of practicing law, and it was one that evolved as she learned more about herself and her strengths in the courtroom.

“Is there any worse feeling than loving someone and knowing that they don’t love you back?” Fairley asked. “There’s nothing worse than unrequited love.”

Fairley went on to argue that the two murders were committed by a vengeful, jilted lover named Ashley Faulkner. The mock case, People v. Faulkner, was one University of Chicago Law School students had been studying throughout the Intensive Trial Practice Workshop—a program that, through rigorous training, practical exercises, and demonstrations, prepares students for every aspect of trial.

Earlier that day, students had written and performed their own closing arguments in front of fellow classmates. Seeing Fairley’s demonstration now, they could appreciate, perhaps, how much her tone and demeanor contributed to the story she told. By then, the workshop was nearly over, and students had spent two weeks practicing trial skills, trying out different litigation styles, working with visiting attorneys of all backgrounds, and receiving faculty encouragement and feedback at each step.

Students would later say that the experience showed them there was more than one way to be an outstanding courtroom lawyer. That it helped them find their most genuine and effective voices. That afternoon at the end of the workshop, Fairley was showing them her way of doing it.

“Ashley Faulkner’s heart wasn’t just broken,” Fairley continued. “It was ripped into a million little pieces.” As she spoke, she tore a piece of paper again, and again, and again.

***

The Intensive Trial Practice Workshop is open to rising third-year students and takes place each year in the two weeks before fall quarter begins. On an average day in the workshop, students are on their feet, speaking in front of their classmates and professors, for more than three hours. In addition to engaging in hands-on exercises, students also attend lectures and demonstrations and study new elements of trial for the following day. The program—which last year celebrated its 25th anniversary—ends with a trip to the Richard J. Daley Center, where students apply the skills and experience they have gathered over those two weeks to present a case before a real judge and a jury made up of local Chicago high school students. It’s an intense experience that offers Law School students a unique preparation for the challenges of putting on a trial. It also provides a relatively low-stakes environment where they can test out different litigation styles until they find the one that fits.

“So much of what we see on television shapes what we think a trial lawyer should be,” said Associate Clinical Professor Erica Zunkel, who is the associate director of the Federal Criminal Justice Clinic and was one of the organizers of this year’s workshop. “But the reality is that you have to figure out what feels comfortable to you so that you can find your voice. What we see over and over again in the workshop is students getting in touch with their voices and who they are as advocates, and there’s really no other comparable opportunity to do that before doing this program.”

Each year, clinical faculty and staff come together to plan, execute, and participate in the program. They also invite judges and attorneys from throughout the Chicago area to demonstrate different elements of trial and offer students feedback during the small group sessions when they practice those elements themselves. This year, that included Fairley, a former prosecutor who completed the trial workshop when she was a student and was recently appointed as a Professor from Practice at the Law School. Seeing the range of styles and techniques litigators use in the real world is critical for new lawyers, said Clinical Professor Herschella Conyers, who has been a driving force behind the workshop since it began 25 years ago.

“I think we can have a preconceived notion about what a good lawyer is, especially a courtroom lawyer,” said Conyers, who is also the director of the Criminal and Juvenile Justice Project. “What we want the students to understand is that there are basic skills, and there are basic rules, but becoming a good litigator—it’s not about the booming voice, it’s not about physical presence. It’s not about gender, it’s not about race, and it’s not about what side you’re on.”

What students learn is that, more than anything, it’s about being genuine. It’s about speaking and acting in a way feels comfortable and true to their individual personalities, because as soon as the jury or the judge detects any discomfort or inauthenticity, they are no longer convinced.

After Fairley finished her presentation that day in the Law School’s courtroom, Jim Mullenix, an attorney with Koehler Mullenix LLC, gave his demonstration of the defense’s closing argument for the same case. Mullenix didn’t use the projection screen, and unlike Fairley, he spoke quickly and adopted an incredulous and sometimes sarcastic tone.

Their styles were very different—and each was very effective.

“There are some attorneys who are really fantastic at what they do,” Fairley said later. “But if I tried to replicate the way they argue myself, it wouldn’t work. It would be completely inconsistent with my personality, my demeanor, and how I come across in a courtroom.”

***

When Clinical Professor Randolph Stone was appointed director of the Edwin F. Mandel Legal Aid Clinic in 1991, he knew he wanted to bring an intensive, hands-on trial advocacy course to the Law School’s curriculum. He had previously taught trial advocacy with Professor Charles Ogletree at Harvard University, and as the Mandel Clinic grew under Stone’s leadership, it became evident that the Law School needed a practical course that would prepare students to be outstanding litigators. Conyers joined the clinic in 1993, and she worked with Stone and other clinical faculty to make the first Intensive Trial Practice Workshop a reality.

“It comes out of the belief that students ought to know something about what to do when they walk into a courtroom, and that to learn the basics on the job may be at the expense of the clients,” Conyers said. “Writing a memo or writing a brief is not the same as walking into a room and convincing 12 strangers or one stranger that they should go your way. And by the time something goes to trial, in most cases, something serious is going on. Lives will be impacted and may be impacted forever. Money is involved. So there was this notion that as a major law school, our students should know as much as possible about how to try a case.”

At the beginning of the workshop, students learn how to develop the theory, or story, of their case and how to fit every witness and piece of evidence they introduce into that story. From there, they tackle opening statements, direct and cross-examinations, exhibits, expert witnesses, objections, closing arguments, and more. The structure of all-day, back-to-back sessions for two weeks—as opposed to meeting once or twice a week throughout the quarter—is intentional, Conyers said. In addition to allowing these skills to build upon each other, it also mimics the fast-paced, thinking-on-your-feet nature of trying a case in the real world.

“You don’t get to put on a witness, wait a week, and come back,” Conyers said. “You might not know when you’ll be on trial, but once you’re on, you’re on. And this structure helps them get a feel for what that’s like. It’s teaching them in real time how to start and finish, from strategy to verdict, in a concise period of time.”

For some students, the workshop is their first intensive experience with public speaking. For most, it is their first time performing in a courtroom setting. It can be nerve-wracking in the beginning, said Clinical Professor Craig Futterman, who is director of the Civil Rights and Police Accountability Project and has taught in the program since he joined the Law School in 2000. But the packed days leave little time for overanalyzing, and the knowledge that all participants are more or less in the same boat soon puts everyone at ease.

“I see students come in from wide-eyed and eager to terrified and everything in between,” Futterman said. “But in terms of knowledge, skill, and an ability to try a case—to deliver an opening statement, to put on or cross-examine a witness, to make objections at the appropriate times—watching them grow from day to day as these skills build upon one another is nothing short of astounding.”

When students practice the various elements of trial, they are also mastering some of the more subtle nuances of trying a case. Jamie Luguri, ’19, enrolled in last year’s trial workshop because she wanted to get hands-on experience in trial advocacy and had heard from other students how useful it was. In addition to all of the tangible skills she learned over those two weeks, Luguri also found that the workshop taught her how to think on her feet.

“You never know what a witness is going to do,” Luguri said. “For the direct examinations and cross-examinations at trial, they brought in witnesses who were acting students, and they would be more likely to go off script, so we had to keep adapting to what they were saying.”

Studying the different styles she observed in demonstrations, and engaging in trial exercises herself, Luguri also learned about her own strengths as a litigator.

“I was more argumentative than some of the other people,” she said. “I think I was good at cross-examinations and closing arguments because those tend to be the places where you’re a bit more combative. I think other people enjoyed opening statements and direct examinations more because they get to tell a story with a witness, whereas in cross-examination, you’re the one telling the story.”

Before the workshop begins, students are divided into small groups that they work with throughout those two weeks. It is in these smaller groups that they practice different trial elements and get feedback from the clinical faculty and visiting instructors. Fairley remembers going through the trial workshop in 2005 and appreciating the chance to work closely with different faculty members in her small cohort. The experience showed her how courtroom lawyers draw from their own strengths and experiences to develop their most effective arguing style.

“That’s what’s so great about the way the course is structured,” Fairley said. “You have a number of faculty members that each of the groups gets exposed to over the course of the two weeks. Law isn’t necessarily all science. There’s some art to it. Different attorneys come from different places, and I thought it was very valuable to hear each of their different perspectives.”

Like Fairley, Judge Manish Shah, ’98, of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois, also completed the workshop as a student and returned to teach in it years later. For Shah, one of the program’s benefits was that it offered a low-stakes environment to test out different arguing styles and techniques.

“It’s an opportunity to try other voices and styles to see which ones fit you,” Shah said. “If you’ve never done it before, you don’t necessarily know what works for you, and having a safe place to experiment is a positive. It’s better to fail in a practice setting than it is in the real world. A workshop environment gives you that opportunity.”

Completing the program last fall, Laurel Hattix, ’19, was struck by its emphasis on storytelling. Good litigators, she learned, can take the facts of a case and organize them into a story that honors their client’s experience and at the same time convinces a jury. Over the course of those two weeks, Hattix found that telling these stories, particularly those in the opening statements and closing arguments, was one of her favorite aspects of putting on a trial.

“I tend to enjoy a more experiential and connected approach to learning, and because of that I feel like there are skills or parts of my personality that can shrink in the traditional classroom environment,” Hattix said. “I think that one of the best parts for me about the courtroom experience was I could take up space as I saw fit. I love the idea of telling a narrative, of being personal and painting a portrait of someone’s life, and I think that this experience allowed me to really flex those storytelling muscles.”

The particular story that litigators choose to tell can make or break a verdict, Conyers said, so the workshop equips students with the tools and practice to tell stories that will offer the jury a cognitive grasp of the facts as well as a moral justification for their decision. This is particularly crucial in the closing argument, she added, where litigators leave their last impression and each side explains in no uncertain terms why they have won the case.

“Jurors have to go home with a moral story, so you have to give them what they need to go home and explain how they came up with their verdict,” Conyers said to students during her lecture on closing arguments. “It must fit the case, and it must fit you.”

***

The Intensive Trial Practice Workshop isn’t difficult for the sake of being difficult, Futterman said of the challenging exercises and long days, it’s difficult because arguing a case and representing a human being in court is difficult. Before going through it, students may not appreciate the preparation, performance, and multitasking that go into putting on a successful trial.

“To be a successful lawyer, much less a successful litigator, we all need to know how to try a case and achieve the optimal result for our clients,” Futterman said. “We have to understand how each aspect of everything we’re doing in preparation—from beginning to end, from the moment we meet our client and learn about the case, to everything that happens after—is preparing us to try and win that case.”

Shah, who served as an Assistant United States Attorney for the Northern District of Illinois from 2001 to 2014, said his experience in the workshop confirmed his interest in becoming a prosecutor and gave him confidence that many young lawyers lack at the beginning of their careers.

“Any fears I had about whether I could actually be the kind of lawyer who argued in court were allayed by going through the workshop in a safe and friendly environment,” he said. “When I became a prosecutor a couple years after law school, I found that even though I didn’t have a lot of experience, and a lot of my peers at the US Attorney’s Office had much more experience than I did, I still had something to fall back on.”

Fairley echoed Shah’s sentiments, saying that the workshop’s hands-on exercises gave her assurance when she argued in court for the first time.

“When you start out as a fledgling prosecutor, you have to go through a training course that’s very, very similar,” Fairley said. “So I was way further along than some of the other lawyers who participated in that program. It gave me more confidence when I stood up to do my first criminal trial because I knew I had the skills to do what needed to be done. I think it was really valuable.”

At the end of the workshop last fall, 10 different trials took place at the Daley Center before 10 sitting judges and around 120 high school students, who acted as jurors. Over the years, Conyers has enjoyed watching how that final trial plays out—the amount of money the jury awards the winner after handing down the verdict varies a great deal from trial to trial, and from year to year. Working with local high school students is a great way to connect with the community, she added, and it’s amazing to see how far the students have come on the last day.

For Hattix, who is planning to be a litigator once she graduates, the trial at the Daley Center was the ideal practice run before arguing a real case for the first time.

“I think it dissipates some of the nerves that we’ll have later on in life, because we’ve had this great trial run of having a judge, and having a jury, and seeing the way in which the judge and the jury respond and react to your arguments,” Hattix said. “Standing in front of a mirror practicing is very different from seeing that human response. Maybe what you thought was compelling or what you thought was great evidence—the jury’s face says something different.”

Though much of the workshop has stayed consistent since it began, it has also changed and grown over the last 25 years. Organizers frequently bring in new visiting attorneys to work with students each fall. Technology has influenced how lawyers tell stories in the courtroom as well as what constitutes evidence—text messages were not yet in wide use in the early 1990s, and Facebook and Instagram didn’t exist—and the curriculum has adapted to keep up with the pace. Last year, the faculty organizers added a panel called Diversity in the Courtroom to help students navigate the biases they might encounter in trial and on behalf of their clients.

“Part of preparing students for the real life of lawyering and succeeding in a courtroom is not shying away from difficult issues,” Futterman said. “When ultimately, it’s not about you as a lawyer, it’s about the people you’re representing, how do you navigate that? How do you navigate sexism or racism that you encounter as a lawyer, while working on behalf of your clients? Especially in a courtroom when dealing with people who have some power over your clients’ lives or freedom, how do we deal with that?”

Offering an intensive trial advocacy course like this may seem like a no-brainer, Zunkel added, but it is hard and time-consuming work. Its longevity, she said, is due in large part to the dedication and expertise that Conyers has brought to the workshop over the last quarter-century.

“I don’t think that this program would have survived without Herschella,” Zunkel said. “She’s really the glue that has kept everything together, and that’s a result of the passion that she has for doing this. It’s the Law School’s good fortune to have her start this, along with Randolph Stone. It shows a commitment to training our students to be great litigators and keeping up with it.”

***

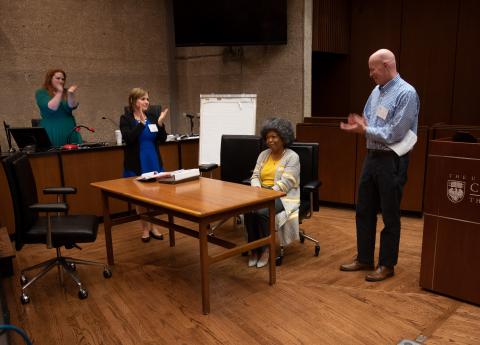

The day before the Daley Center trials last fall, clinical faculty honored the Intensive Trial Practice Workshop’s 25th anniversary and Conyers’s crucial role in leading and organizing the program. Standing up in front of the students, faculty, attorneys, and judges who had been a part of the program last year, Zunkel thanked Conyers—who was not expecting the speech—for everything she has done to make the workshop thrive for so many years.

“This workshop is really special, and the heart and soul of the workshop is you,” she said to Conyers before looking back at the audience. “It is no small task to organize, and this is something that Herschella has been doing year, after year, after year. She’s so giving of her time and her brilliance, and we couldn’t be luckier to have her as a colleague and a professor at the Law School, and her clients could not be luckier to have her as their attorney.

We owe her a tremendous debt of gratitude for all she has done to make this incredible program such a great learning experience for so many people for all of these years.”

When Shah looks back on his experience as a student in the workshop, he remembers not just learning how to develop the theory of a case, but the importance of keeping that theory in mind throughout the trial and questioning at every stage whether a piece of evidence or particular fact advances that theory. It’s something he still thinks about to this day. He also remembers how different his experiences in the workshop felt from those in the classroom, because rather than reading or learning about the different elements of trying a case, he did them himself.

“Not every University of Chicago student is destined for academia,” Shah said. “As a sitting trial court judge in the federal courts, I can tell you that the real world needs super smart, effective trial lawyers—and the University can produce super smart, effective trial lawyers by giving them this kind of experience within the rigors and demands of the University of Chicago Law School. I think it’s an incredibly valuable feature of the [University’s] legal education.”