‘The Best Postdoc You Could Ever Have’

The first time Byron White called Robert Barnett, ’71, the young lawyer didn’t believe he had a US Supreme Court justice on the other end of the line. Barnett was sure it was Barry Alberts, ’71, who was famous among their recently graduated classmates for his uncanny impressions of Law School faculty. It wasn’t hard to imagine Alberts mimicking a distinguished jurist.

“Barry, what are you doing?” Barnett said, impatiently. Barnett was living in New Orleans, clerking for Judge John Minor Wisdom on the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit—his first job out of law school. Alberts was working for a firm back in Chicago.

“Who’s Barry?” the caller said. “This is Byron White.”

Barnett sighed, unconvinced: “I’m going to work now, Barry. Leave me alone.”

“It’s Byron White,” the voice said again.

And so it was: Justice White, calling to offer Barnett a job as a law clerk for the Court’s 1972–1973 term. The conversation—which improved once the confusion subsided—launched what Barnett, now a prominent Washington, DC, lawyer, calls “another treasured and unique and wonderful year,” a chance to continue refining the writing, research, and advocacy skills he’d been building on the Fifth Circuit.

But it proved to be part of a longer thread, too. That same term, Barnett’s classmate Geoffrey R. Stone, ’71, now the University of Chicago’s Edward H. Levi Distinguished Service Professor of Law and a former dean of the Law School and former provost of the University of Chicago, clerked for Justice William J. Brennan Jr. Together Stone and Barnett marked the start of a Law School streak: for at least part of each of the past 47 years, at least one Law School graduate has clerked on the US Supreme Court. The unbroken record comprises 143 alumni, including four who will clerk this term. It echoes the success of many other Law School alumni who have been part of the Supreme Court’s clerkship program (which celebrates its 100th year this fall): people like Professor Emeritus Kenneth Dam, ’57, a former University of Chicago provost and former deputy secretary in the US departments Treasury and State; Dallin Oaks, ’57, a distinguished Mormon leader; and Rex Lee, ’63, a former US solicitor general.

But even more, the record tells a broader story about the extraordinary ways in which clerkships shape young lawyers, the relationships that emerge, and the role that the Law School has played in supporting its students’ clerkship ambitions, even as the legal market and clerkship hiring practices have shifted.

“My own clerkships made me professionally mature and sensitive to the nuances of the legal system— they made me a smarter lawyer,” said Senior Lecturer Dennis Hutchinson, who led the Law School’s clerkship hiring for more than two decades beginning in the 1990s. He had three clerkships of his own between 1974 and 1977: with Elbert P. Tuttle on the Fifth Circuit, White on the Supreme Court, and William O. Douglas on the Supreme Court. “One thing I’ve always said to the students: this is the best postdoc you could ever have. One of the reasons our [clerkship] numbers have grown is that faculty and the Office of Career Services have built a structure that has really gotten the word out about the [benefits of] clerkships.”

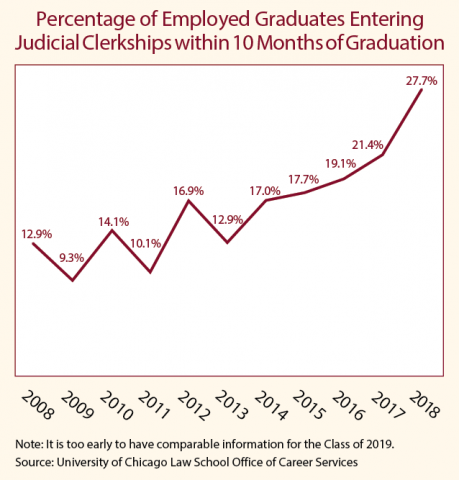

In recent years, the number of Law School alumni in judicial clerkships at all levels in the state and federal system has skyrocketed, rising from 46 in October Term 2008 to 115 in October Term 2018. In 2018, 27 percent of Law School students entered state or federal clerkships immediately after graduation—the highest figure in recent memory, and more than double the 12.9 percent who entered clerkships immediately after graduation in 2013.

“When a judge hires a Chicago student or alumnus to clerk, they invariably get someone who has learned a ton of law but also is fluent in the latest theory, is diligent and bright, knows how to grapple with skeptical questioning, and is used to solving problems and debating ideas with people who think differently than they do,” said Professor Lior Strahilevitz, who now leads the clerkship committee with Professor Jonathan Masur. “What Chicago clerks offer is what every great jurist wants in a clerk.”

Like all members of the faculty committee, the chairs are former clerks: Strahilevitz clerked for Judge Cynthia Holcomb Hall on the Ninth Circuit and Masur clerked for clerked for Chief Judge Marilyn Hall Patel of the United States District Court for the Northern District of California and for Judge Richard Posner on the Seventh Circuit. The faculty clerkship committee works with the Law School’s career counselors to provide rigorous, individualized guidance for every student who expresses an interest in clerking. They emphasize the benefits of different types of clerkships, including the ability to leverage a lower court clerkship into one at an appellate court; expose students to the judiciary through a variety of programs; and offer access to a storehouse of data on alumni who have clerked.

“During my 1L year, I [encountered] professors and alumni who had clerked and who said it was an amazing experience—a chance to deepen one’s learning about the law and understand how it works in reality for the litigants. And they talked about district and appellate court experiences as being pretty different, so I ended up applying to both,” said Roisin Duffy-Gideon, ’18, who clerked for Judge Edmond Chang on the District Court for the Northern District of Illinois during the 2018–2019 term and is clerking for Judge William Kayatta on the First Circuit this term. “I felt very supported. Many of these same professors were willing to talk me through that process and help me understand what hiring looks like and how and when it would happen. I remember when I first got the interview offer from Judge Chang, I stopped by three of my professors’ offices—I think it was a Friday afternoon—to ask if I could talk to them for five minutes, just to think through the interview. They were all there, and they were all happy to help. That was pretty amazing.”

This term, at least 50 Law School alumni will clerk on the US Court of Appeals, 45 will clerk on federal district courts, and nine will clerk on state appellate courts (these numbers were accurate as of September; updates can be found here). In addition, four alumni will clerk on the Supreme Court: Mica Moore, ’17, will clerk for Justice Elena Kagan; Kelly Holt, ’17, and Stephen Yelderman, ’10, will clerk for Justice Neil Gorsuch; and Caroline Cook, ’16, will clerk for Justice Clarence Thomas. All four clerked on the US Court of Appeals before earning their Supreme Court spots.

“These are four extraordinary lawyers who were each tremendously successful students at the Law School and whose futures couldn’t be brighter,” said Strahilevitz, the Sidley Austin Professor of Law. “Supreme Court justices are hardly alone in noting the remarkable quality of our graduates. Throughout the federal and state judiciaries, Chicago students and alumni are in especially high demand.”

It is typical for the Law School to have multiple alumni clerking on the Supreme Court at once: in 37 of the past 47 years, two or more clerks on the Supreme Court have been graduates of the Law School. In 15 of those years, four or more Supreme Clerks have been Chicago alumni—including in 1993, when there were eight, and 1994, when there were seven. There were four at one time as recently as 2017, when Nick Harper, ’15, and Krista Perry, ’16, clerked for Kennedy; Eric Tung, ’10, clerked for Gorsuch; and Gilbert Dickey, ’12, clerked for Thomas.

“More and more of our students come to law school hoping to clerk,” said Masur, the John P. Wilson Professor of Law. “And they’re right to want to. Clerkships are great jobs, great learning experiences, and great opportunities to find a lifelong mentor. They can also jump start a student’s career. Our goal as a clerkship committee is to tell students about the advantages of clerking and then to help find a clerkship for each and every student who wants one.”

Introduction to the Judiciary

Manish Shah, ’98, a judge on the US District Court for the Northern District of Illinois since 2014, had his first judicial experience as a clerk on the same court.

For two years beginning in 1999, he clerked for Judge James B. Zagel, an experience that he said gave him a “crash course” in many topics and areas of law, offered an opportunity to work through complex issues, and connected him with a valued mentor.

“I loved my clerkship and really benefited from the opportunity to get to know Judge Zagel and work with him closely and get to know him personally,” Shah said. “Eventually the relationship became one of mentorship and then, many years later, a friendship. His chambers was a very friendly environment. There was a lot of social interaction with the judge and that was a great way to get to know him and, in a way, demystify the judiciary by having that kind of personal relationship.”

Shah and other alumni judges routinely return to the Law School for a variety of programs: to judge the Hinton Moot Court competition (which Shah did in 2018), to speak at student-run events, or to participate in the Edward H. Levi Distinguished Visiting Jurist lecture series.

The Distinguished Visiting Jurist program started in 2012 to support interaction between judges and students and faculty members. Jerome S. Katzin, ’41, endowed the program in 2013 with a $1 million gift that named the program in honor of Levi, a longtime Law School professor who served as dean, president of the University, and US attorney general.

Since the program began, more than two dozen judges have visited the Law School, delivering lunch talks and often meeting with a small group of students and faculty. Recent visiting jurists have included Merrick Garland, chief judge of the DC Circuit; Michelle Friedland of the Ninth Circuit; Timothy Tymkovich, chief judge of the Tenth Circuit; Cheryl Krause of the Third Circuit; Jeffrey S. Sutton of the Sixth Circuit; John Z. Lee of the US District Court for the Northern District of Illinois; and Beryl Howell, chief judge of the US District Court for the District of Columbia.

“A major goal of the Levi program is to help our students, especially 1Ls and 2Ls, get comfortable with judges and realize that they are people too, albeit very accomplished ones,” said Strahilevitz, who coordinates the program. “When their schedules permit, we always have the judges meet with anywhere between a dozen and two dozen students over breakfast. One of the hardest parts of my job is walking into those breakfasts to let everyone know it’s time to take the judge to his or her next event. The judges and the students alike look really disappointed when I enter the room! And I’ve gotten used to having the judges tell me how lucky we are to get to teach Chicago students every day, a sentiment I share.”

The Law School has also responded to changes in the clerkship hiring market. In the past several years, following changes in the previous hiring plan judges used to hire entry-level clerks, the faculty clerkship committee and the Office of Career Services enhanced its system for helping students navigate the application process. Career Services devoted additional staff to clerkship hiring—a project now led by Susan Staab, the Law School’s director of judicial clerkship outreach and support—and increased messaging that encouraged all students with clerkship aspirations to take advantage of one-on-one counseling and interview coaching.

“It’s an amplification of what we were already doing really well,” Associate Dean for Career Services Lois Casaleggi said.

The faculty clerkship committee expanded several years ago to include Professors Genevieve Lakier, John Rappaport, and Daniel Hemel. Along with Masur and Strahilevitz, they each share their deep knowledge of the experience, the judges, and the application process with students, guiding them during law school and, often, for several years after.

But guidance often comes from other faculty throughout the building, too. Lecturer Adam Mortara, ’01, a former clerk for Justice Clarence Thomas of the Supreme Court and Judge Patrick E. Higginbotham of the Fifth Circuit and now a partner at Bartlit Beck LLP, has advised countless students over the years. Among them was Taylor Meehan, ’13, who recalled that it was Mortara who encouraged her to pursue clerkships and then guided her through the application and interview process.

“He pointed me toward Justice Scalia’s A Matter of Interpretation—a book I still refer to from time to time today,” said Meehan, who clerked for Judge William H. Pryor Jr. on the US Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit during 2013–2014 and for Justices Antonin Scalia and Thomas during the 2015–2016 term. (Scalia passed away during her clerkship, and she finished out the term clerking for Thomas.) “More importantly, [Mortara] instilled in me some confidence that I was deserving of the job.”

Nick Spear, ’14, recalled how Stone helped connect him with the federal appellate judge for whom Spear worked after graduation.

“I got an email from Geof Stone one night, and he said something to the effect of, ‘Hey, my friend Andrew Hurwitz, a Ninth Circuit judge, is looking for applicants, and I’ve heard you might be interested in the Ninth Circuit—would you like me to pass along your application?’” Spear said. “Professor Strahilevitz and Professor Hutchinson knew that I was interested in going out there. But I’d never gone to [Stone] and said, ‘Can you connect me with this judge?’ He had heard through the grapevine that this was something I might want and reached out to me. Just the fact that [they were all] looking out for me . . . There’s this desire to find out what each student wants and try to get us into that professional world.”

Spear spent a year with Hurwitz and then moved into a second clerkship, with Judge Philip S. Gutierrez of United States District Court for the Central District of California—and the experiences had a big impact.

“I got to sit down with brilliant people and think through problems, the same way I did in law school,” Spear said. “But this time the answers had a real-world effect. Clerking was transformative.”

In addition to giving students a chance to hear from judges, the Law School also maintains what Casaleggi calls a “treasure trove” of data on alumni clerkship experiences, much of which is available in a judicial clerkship manual that gets distributed to every interested first-year student.

“OCS has done a fabulous job of staying in touch with alumni,” Hutchinson said. “There’s this bank of responses from people who have clerked. [OCS has asked] ‘What was your clerkship like? What was the attire for your interview? How long did it last? Who did you see? What were the working conditions? What were you assigned to do? What were the hours?’ These are great resources.”

Meehan still remembers how alumni seemed to “come out of the woodwork” when she was preparing to interview with Scalia.

“They helped me think about how to prepare for the interview and even asked me mock questions,” said Meehan, now an attorney at Bartlit Beck. “The alumni network at the Law School was incredibly helpful.”

Her first experience, clerking for Pryor in Birmingham, ended up giving her memorable—and incredibly valuable—experiences.

“I remember very vividly my first case with Judge Pryor and seeing him outsmart me in every way,” Meehan said. “It’s humbling to begin with to walk into a judge’s chambers every day for work, but then handing them work product—that’s all the more humbling.”

Scalia would meticulously “book” the opinions his clerks had drafted, rereading original citations and going over the work word for word, Meehan said. “He really wanted to get it right,” she said. “Being able to sit there right next to him and watch him mull over prior Supreme Court decisions was really eye opening.”

For many clerks, their judges become lifelong mentors; Meehan is still in touch with both Pryor and Thomas. “I tend not to make career decisions without consulting them,” she said.

A Front-Row Seat to History

The year Barnett clerked for White, he witnessed a young ACLU attorney named Ruth Bader Ginsburg deliver her inaugural Supreme Court oral argument in Frontiero v. Richardson. (Stone, who was clerking for Brennan, drafted the Court’s plurality opinion in that case for his boss.) Barnett also dined with Justice Thurgood Marshall, saw famed constitutional lawyer Charles Alan Wright argue a case, and joined his co-clerks in basketball games against White, a renowned athlete, on the Court’s in-house court—games so intense that Barnett ended his year having broken both an ankle and a hand. Barnett experienced the grandeur of the High Court on many occasions; he once watched a lawyer exit the Courtroom by backing out and “bowing every three steps.”

This, of course, was the term the Court decided Roe v. Wade—although the ruling didn’t feel like the political lightning rod it would eventually become. “I knew it was momentous, but did I think we’d still be arguing about it in 2019?” Barnett said. “I don’t think I did.”

The issue wasn’t as controversial in 1973 as it is now, Stone said. Still, as law clerks, Stone and Barnett had front-row seats as the justices wrestled with the historic decision.

“Brennan, I think, was feeling conflicted about abortion, being the Court’s only Catholic—but he put that aside and recognized that his responsibility to justice was to examine the question not from the perspective of a Catholic, but from the perspective of a justice on the Supreme Court,” Stone said. “I was very admiring of Brennan’s awareness of this and his understanding of the importance of . . . addressing the question neutrally.”

Barnett vividly remembers seeing Justice Harry Blackmun bent over a desk in a corner of the Supreme Court library, writing the majority opinion. Similarly, Stone remembers seeing Blackmun late at night poring over the thousands of letters the Supreme Court received after they handed down the 7–2 decision in January 1973.

Stone’s boss, Brennan, had played a critical role in the majority opinion. Barnett’s boss, White, dissented.

“He wrote that one himself,” Barnett said of White’s dissent, which hinged on the belief that the Court had no basis for deciding between the competing values of pregnant women and unborn children. “He didn’t want to put it on any of us.”

It was a heady year, one that would resonate with Stone as he built a career as one of the nation’s foremost experts on civil liberties and with Barnett as he built a successful and diverse practice that has included representing Barack Obama, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and other top government figures as they transitioned into the private sector.

“I learned how the judicial process works from the inside, which is invaluable,” Barnett said. “I also learned the importance of research. I learned to write better. I learned advocacy skills that have stood me well for all these years. But most important were the amazing personal relationships that you make that last for a lifetime.”

But a clerkship doesn’t have to be at the highest levels to provide an excellent experience. Much of the emphasis when counseling aspiring law clerks is on finding the right fit. Hutchinson made a point of meeting with interested students one-on-one—and that practice continues today.

“What I tried to explain to students interested in clerkships is you have to tailor what your talents are and what your ambitions are with what a clerkship might do for you,” Hutchinson said. “So somebody who wants to go back to central Texas because she loves the Hill Country should think about a Texas Supreme Court clerkship. It’s that sort of tailoring that gets students to see a broader array of possibilities that are fully consistent with their own ambitions.”

Although this wasn’t always the case, clerkships on lower courts now are an important step for students seeking to clerk on the US Supreme Court. The clerkship experience also is valuable for students entering careers in law firms, public interest, or any other area of the profession.

“So much of law school is about learning how judges decide cases,” Masur said. “What better way to gain that knowledge than to work closely with a judge? Whether a student’s destination is public interest or a large law firm, transactional practice or litigation, I can hardly think of a more valuable way to spend a year after graduation.”