Law Students Present Investor Advocacy Ideas to SEC

Sitting in her winter quarter Securities Regulations course, Angel Lockhart, ’22, was frustrated by statistics showing the household net worth of Black and White families, and the possible correlation to business formation. So when her professor, Todd Henderson, mentioned that a small group of Law School students would have the opportunity to present investor advocacy proposals to the US Securities and Exchange Commission in the spring, she knew she was interested. And she knew she wanted to spend her quarter thinking about how securities law could play a role in closing wealth and investment gaps between men and women and between White people and people of color.

“I kept thinking, ‘Why isn’t there a solution to this huge wealth gap? What are we going to do about it?’” said Lockhart, who ultimately worked with Will Shirey, ’21; Megan Anderson, ’21; and Leonor Suarez, ’22, on a proposal to require institutional investment and venture capital firms to disclose statistics about fund managers’ gender and race—a move that she and her team argued would expand representation, and, in turn, increase trust and ultimately market participation by women and racial minorities.

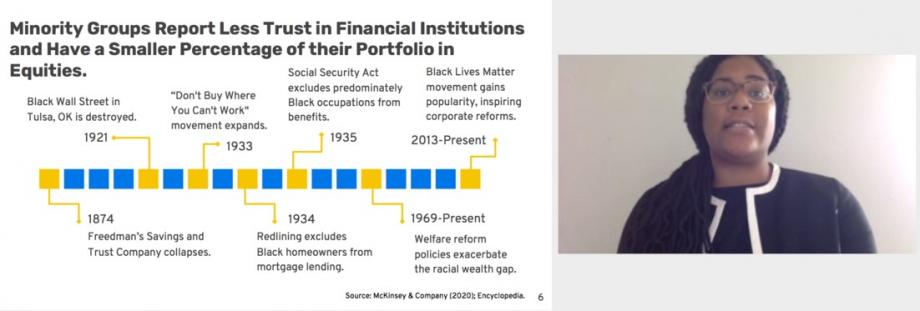

“When you look at the history, you see that trust and transparency matter, and this adds transparency,” Lockhart said, pointing to an 1874 bank collapse that eroded trust among thousands of Black depositors, as well as historic and current movements to focus spending in areas and at businesses that support the Black community. The requirement, she added, would also “add accountability because nobody wants to have to explain why [their hiring isn’t inclusive].”

In May, Lockhart, Shirey, Anderson, and Suarez were among 14 University of Chicago Law School students who presented ideas to the SEC as part of the regulatory agency’s Investor Advocacy Engagement Series: University Roundtables, a set of listening sessions designed to encourage input on rulemaking and policy issues. The Law School was one of several schools to participate in the series.

The Law School students, who were divided into four teams, developed their ideas as part of a spring quarter seminar taught by Henderson, the Michael J. Marks Professor of Law; Joshua Macey, assistant professor of law; and Deputy Dean Anthony Casey, the Donald M. Ephraim Professor in Law and Economics and the director of the Law School’s Center on Law and Finance, which worked with the SEC to help organize the Law School roundtable.

At that roundtable, on May 26, the students delivered their PowerPoint presentations via Zoom to a group that included SEC Commissioner Hester M. Peirce, SEC Investor Advocate Rick Fleming, and staffers from a variety of SEC departments.

“I was so impressed with the attention [Peirce] gave—I told the students afterward that it isn’t something that happens all the time that you get this kind of attention and feedback and engagement on your ideas at this level,” said Henderson, a leading expert in securities regulation.

The Law School teams took on a variety of ideas, meeting weekly with their professors to talk through and develop their ideas and presentations.

Nicole Briones, ’21; Dane Christensen, ’21; and Claudia Wang, ’22, examined the surge in Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs) and proposed that the SEC clarify entity-related definitions under the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act (PSLRA) rather than enhancing certain SPAC redemption and dilution disclosures.

Paul Boswell, ’21; Dario Panza, LLM ’21; Bailey Swainston, ’22; and Griffin Clark, ’22, explored the regulation of crypto assets, proposing an ex ante safe harbor that would allow crypto assets to develop without registering as securities as long as they meet certain decentralization requirements.

And Sakina Haji, ’21; Spencer Slabaugh, ’22; and Jacob Mitchell, ’22, took on the gamification of investor trading apps. They proposed updated investor protections beyond the current system, which typically involves self-disclosure surveys in which participants, regardless of investing experience, estimate their own abilities, risk tolerance, and investment objectives in order to access higher levels of trading.

“The topics the students chose were all very much ones that are in the news and top of mind—they were writing about live issues,” Henderson said. “How should we be regulating crypto currency? What should we do about the wealth gap? These are vitally important questions.”

Henderson said he particularly “impressed and proud” to see the students’ ideas evolve over the course of the quarter as they considered not only possible solutions but how those solutions would fit the current regulatory structure.

“My sense from watching the teams was that many of them came in with a particular hypothesis about what their end result was going to be or about what the right answer was—and then, through their own discovery and through their own process of engaging, we would see them learn and change their views,” Henderson said. “They really put themselves in the commissioners’ shoes, [asking], ‘How should we think about this? What constraints does that government have?’ So they weren't falling into this idea of, ‘Let’s wave a magic wand and the world's a better place.’ It was a deeply serious intellectual exercise.”

It was also a creative one that required the students to consider their delivery, thinking about how to assemble the information into a cohesive narrative, when and where to incorporate visuals, and how to capture their audience’s attention, Henderson added.

Haji said she enjoyed taking on a current issue and then thinking about solutions that might resonate with the SEC. Gamification had been in the news: after trading on the brokerage app, Robinhood, contributed to a spike in GameStop shares earlier this year, regulators raised concerns about game-like investment platforms, wondering whether it was too easy for inexperienced investors to gain access to riskier financial markets.

Indeed, Haji said, it is relatively easy to manipulate the self-disclosure questions to “level up” to riskier investment strategies, and the game-like approach can be addictive. But there are benefits, too—including increased engagement, motivation, and information retention—and she, Mitchell, and Slabaugh didn’t think it made sense to take an “anti-gamification” stance. Instead, they pitched an approach that would build gamified investor education directly into the investing apps and require users to demonstrate knowledge before leveling up.

“To be able to take an issue that is very much on people’s minds right now and actually come up with something concrete to say about it and propose it directly to people who are in a position to make change—that was really rewarding,” said Haji, who interned at the SEC the summer after her 1L year. “It was just such a cool experience, and something I didn’t think I’d have a chance to do while still in law school.”

Lockhart said she was grateful for the opportunity to study investor access—and to work with her three teammates, none of whom she knew before enrolling in the seminar.

“We were all excited about [studying] investor access and diversity, and we were passionate about figuring out solutions,” Lockhart said. “I’m extremely happy that I participated—even beyond presenting to the SEC, I enjoyed working with Megan, Will, and Leonor—they were an amazing team.”