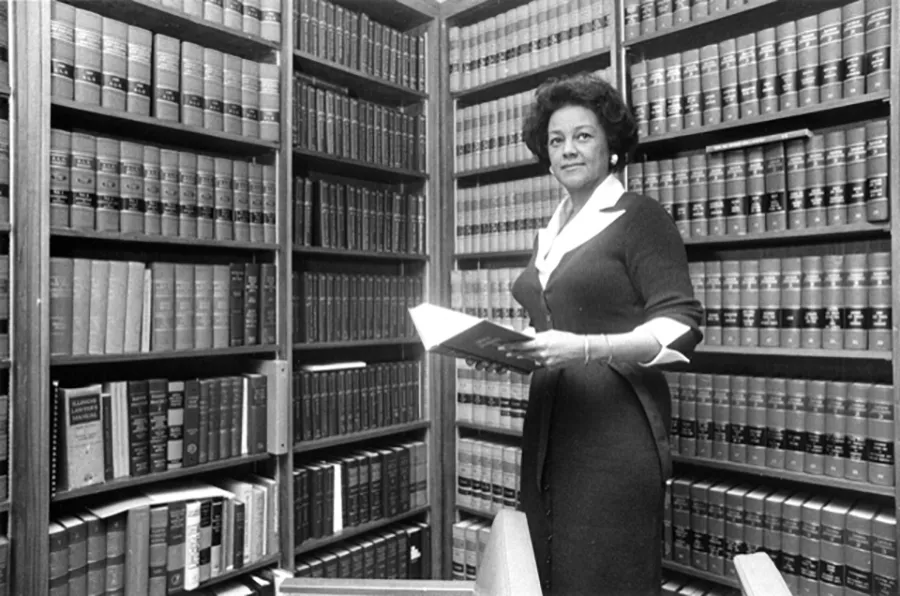

Remembering Jewel Lafontant, ’46, in Honor of Women’s History Month

Jewel C. Stradford Lafontant’s career path was marked by many firsts.

In 1946, she became the first African American woman to graduate from the University of Chicago Law School.

In 1955, she became the first African American woman to serve as assistant US attorney for the Northern District of Illinois.

Then in 1973, she was the first woman to be appointed Deputy US Solicitor General.

Her distinguished career reflects a woman on a mission, determined to make a difference in whatever role she occupied. And a difference she did make, shattering many glass ceilings for women and minorities in politics and corporate America.

But who was Jewel Lafontant and what inspired her to blaze these trails?

A Foundation of Social Justice Advocacy

Lafontant was born Jewel Carter Stradford in 1922 to a prominent and high-achieving African American family. Her father, C. Francis Stradford, was an attorney and co-founder of the National Bar Association, and her mother, Aida Arabella, was an artist and homemaker.

Her grandfather, J.B. Stradford, was also a prominent attorney and the owner of the only Black hotel in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Her grandmother, Bertie Wiley Stradford, was also college educated, making Lafontant third generation college educated.

Lafontant cited her parents as being her biggest inspirations growing up, though for different reasons.

The voice of her mother—get an education, become independent, do what you want to do—rang in her head, fueling her with a confidence she would carry with her throughout adulthood. “I never had an idea that I couldn’t be a lawyer, that I couldn’t be successful,” she said during one interview.

In her father’s case, it was his legal work that made a deep impression on her. One family story in particular planted the idea that the law could “save lives.”

During the Oklahoma race riots of 1921, Lafontant’s grandfather’s hotel and other properties were burned to the ground, and he had to flee Tulsa. C. F. Stradford saved his father by fighting his extradition proceedings. Had J. B. Stradford been forced to return to Tulsa in those days, he might have been killed.

The idea that the law could bring about change took deeper root for Lafontant when she worked in her father’s law office during her high school summers. She was his secretary when he worked on the landmark 1940 Supreme Court case Hansberry v. Lee, which struck down racially restrictive housing covenants.

All of this lit a flame for Lafontant. She followed in the footsteps of her father and grandparents and attended Oberlin College, where she earned her political science degree. She flourished there, becoming president of Liberal Club and captain of her class volleyball team, to name just a few of her activities.

After Oberlin she enrolled at the Law School, where she met her first husband, John W. Rogers, ’48, a Tuskegee airman attending on the GI Bill.

As a student, Lafontant grew to be very politically active. She had always witnessed her parents fighting any form of segregation, so it was no surprise that she did the same. She participated in sit-ins in Chicago restaurants, where she was spat on and physically abused, and she brought lawsuits against many non-integrated restaurants, forcing them to close.

After graduating, Lafontant initially had trouble finding work. White-owned law firms refused to hire her, and the American Bar Association refused her membership, though they later admitted her.

Eventually, Lafontant became a trial attorney where she handled landlord-tenant disputes—then in 1955, President Eisenhower appointed her assistant US Attorney for the Northern District of Illinois. She resigned in 1958 after giving birth to her only child, John W. Rogers Jr., who would grow up to become the founder of Ariel Capital Management (now Ariel Investments).

Soaring in Her Vocation

Lafontant’s desire to continue her career after motherhood had apparently created mounting tension between her and her husband, as it was customary in those days for women to stay at home with their children. The two divorced when John Jr. was three years old and Lafontant went on to join her father’s law practice.

Later, she met a lawyer who would become her second husband: H. Ernest Lafontant, a native of Haiti. After marrying, the two went into practice with her father in a firm called Stradford, Lafontant & Lafontant.

In 1963, Lafontant won her first case in the US Supreme Court: Lynumn v. Illinois. She argued that the confession of her client, Beatrice Lynumn, was not legally admissible since the police had coerced Lynumn by threatening to take her children.

The landmark case Miranda v. the State of Arizona drew on Lynumn v. Illinois—which Lafontant considered to be the most significant case of her career.

In the 1960s, Lafontant became increasingly active in the Republican party. She seconded the nomination of Richard M. Nixon for President and, running on the Republican ticket, became the first woman nominated for a seat on the Superior Court in Illinois.

She again became “the first woman” when President Nixon appointed her as Deputy US Solicitor General in 1973, making her the highest-ranking woman in his administration.

Lafontant kept on blazing forward in the male-dominated legal world of her time, expanding to the corporate arena where she served on more than twenty executive boards over the course of her career. She served on the boards of Jewel Companies, Mobil, Equitable Life Assurance, Trans World Airlines, Revlon, Hanes, and eventually her son’s firm, Ariel Capital Management. She also served on the boards of Oberlin College, Howard University, and Tuskegee Institute.

“I had started out as what they call a ‘token’ because you’re black, you’re female, and people assumed you’re just there as a figurehead,” said Lafontant in an interview she did with HistoryMakers in 1993. “But then when the president of one of the major corporations invited me to come on the board, he said, we’re inviting you on the board because of your expertise, Mrs. Lafontant, and your knowledge. And to me that was one of the greatest days and moments I’ve had, to be recognized for your ability, to be recognized for what you can bring to a company, and that you can actually help a major, billion-dollar company.”

Throughout the 1980s, Lafontant continued to evolve in her leadership. Under George H. W. Bush, she became US Ambassador-at-large and US Coordinator for Refugee Affairs, a role that had her traveling all over the world. She also served as the Vice Chairperson of the US Advisory Commission on International, Educational, and Cultural Affairs.

Throughout her career, Lafontant received many honors and awards for her professional success and her dedication to social causes.

“The law is still the greatest vehicle through which to bring about justice and equality,” she had said on more than one occasion—and she truly lived her mission.

Following the death of her second husband in 1976, Lafontant married international business consultant Naguib S. Mankarious in 1989.

She died of breast cancer at the age of 75 in 1997 as Jewel C. Stradford Lafontant-Mankarious.