The Unwritten Constitution of Foreign Affairs

Foreign affairs law in the United States has evolved significantly since the US Constitution first took effect more than two centuries ago. But that evolution did not come about through amendments to the text of the Constitution, which is extremely difficult to change, nor from US Supreme Court rulings. Rather, it came from what Curtis A. Bradley calls “historical gloss”—an accumulation of governmental practices that have created nonjudicial precedents for decision-making.

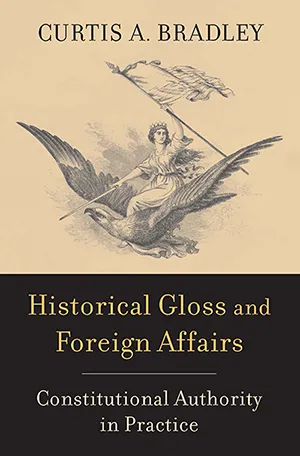

In his new book, Historical Gloss and Foreign Affairs: Constitutional Authority in Practice, Bradley documents the process of historical gloss in action, illuminating how Congress and the executive branch have relied on the accretion of governmental practice to determine how to conduct foreign relations over the course of US history. He asserts that much of the constitutional law on foreign affairs is not actually in the text of the Constitution.

“Both the United States as a nation and the world itself have changed dramatically since the Constitution was written back in the 1780s,” explained Bradley. “As the US has become more involved on the global stage and emerged as a superpower, the laws that govern how we interact with the rest of the world have naturally evolved with it.”

Bradley is the Allen M. Singer Distinguished Service Professor of Law and an expert in international law and foreign relations law. In Historical Gloss, published by Harvard University Press last October, Bradley presents a new constitutional theory that highlights the importance of gloss in interpreting the Constitution. He argues that gloss is a longstanding form of constitutional reasoning, separate from reliance on the original meaning of the Constitution although not necessarily in opposition to it.

“Even in the earliest days, when the Constitution was merely a decade old, the government actors of the time were already drawing legal conclusions from gloss,” he said.

In researching the book, Bradley took a deep dive into the historical materials that illustrate how presidential administrations and members of Congress engaged in decision-making. He said he found references dating back to the early 1790s of US government officials saying in essence, “We now have some practice; let’s be guided by what has happened."

The book covers four major foreign affairs powers to illustrate gloss in action: the power to recognize foreign governments, the power to make non-treaty international agreements, the power to terminate treaties and executive agreements, and the power to use military force.

For the United States to enter into a treaty with a foreign country, the Constitution stipulates that two-thirds of the Senate must agree with the president. In practice, it would be extraordinarily difficult to hold Senate votes on all the treaties and international agreements that the United States enters into, which today average more than 200 a year.

“It just doesn’t happen,” said Bradley. “We wouldn’t be able to develop a lot of international law if every agreement had to go through the Senate. So, over time, presidents have concluded many international agreements and treaties without using the two-thirds provision.”

Bradley says that practices such as these have come to be viewed as constitutional, not because of what the text says, but because institutional actors have repeatedly accepted and relied on them: “Both the executive and legislative branches have acquiesced in this easier and more flexible way of making agreements, for example, and both major parties have accepted the practice,” he said. “When the courts do occasionally get involved in issues like these, they have traditionally given the practice a lot of weight as well.”

The term “gloss” to describe historical governmental practice was coined by US Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter who said in his 1952 concurring opinion in Youngstown Sheet and Tube v. Sawyer: “[It is] an inadmissibly narrow conception of American constitutional law to confine it to the words of the Constitution and to disregard the gloss which life has written upon them.”

Bradley said one way to think of gloss “is to imagine a medieval manuscript that has been annotated by expert scribes, with explanations that provide further insight to the reader on the meaning of the text. That’s really where the term originated from.”

While Bradley presents several case studies in his book to illustrate the implementation of historical practice in the development of foreign affairs law, he acknowledges that a reliance on gloss can lead to outcomes that expand executive power at the expense of both Congress and the courts. He notes, however, that Congress has also benefited from longstanding practices, particularly with respect to its ability to impose checks on the president.

Ultimately, Bradley leaves it to readers to decide whether our practice-based approach to constitutional authority in foreign affairs produces good outcomes.

“The main claim of the book is that a lot of our constitutional law is not to be found in the Supreme Court of the United States,” he said. “We spend so much time studying those small number of decisions that the Supreme Court issues every year—and I’m not saying that that’s not important; I study them too. What I’m saying is that much of our constitutional law is actually developed, interpreted, and applied outside of the courts, as seen in the particular example of foreign affairs. It’s an important part of the landscape of US constitutional law that I don’t think is studied and thought about enough.”