Reclaiming Sophonisba

It wasn’t easy being a female lawyer in the late 19th century, but that didn’t stop Sophonisba Breckinridge from trying.

About a decade before the she became the University of Chicago Law School’s first female graduate in 1904, the future activist and social reformer—the daughter of an attorney and congressman—litigated a few cases in her home state of Kentucky, where she was admitted to the bar in 1892.

But as much as she strived to break down barriers, practicing law ultimately wasn’t how Breckinridge wanted to make change. She preferred policy reform and education—and she valued collaboration over solo recognition. In fact, her short and little-known foray into legal practice stands in contrast to her future approach: one that would place her in the midst of nearly every reform campaign of the Progressive and New Deal era but would keep her from attaining the fame of people like Hull House founder Jane Addams, a friend with whom Breckinridge worked closely.

“Breckinridge worked as a policy consultant rather than as an in-the-streets activist … and she shied away from the spotlight,” said University of Montana history professor Anya Jabour, whose new book on the enigmatic figure aims to “reclaim Breckinridge from historical amnesia.” “She was second in command virtually everywhere she went.”

Breckinridge, of course, hasn’t been forgotten at the University of Chicago, where she co-founded the School of Social Service Administration and helped build its curriculum based on the Law School’s case method. (SSA’s Doctoral Program is celebrating its 100th year.) Her photo hangs on a wall in the Law School, and various entities on campus, including an undergraduate housing community, bear her name. At the University of Chicago, Breckinridge became the first woman to earn a PhD in political science and the first woman granted a named professorship. In 1905, she also began teaching what may have been the first women’s studies course in the United States—a class in the University’s Department of Household Administration that focused on the legal and economic status of women.

But outside of Hyde Park, Breckinridge—who was internationally known before her death in 1948—has largely faded from memory.

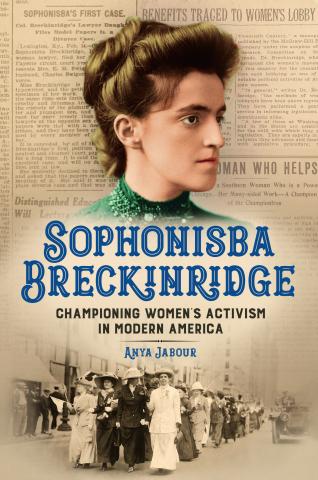

Jabour, who spent 10 years researching Breckinridge, hopes to change that. Her book, Sophonisba Breckinridge: Championing Women’s Activism in Modern America (University of Illinois Press) traces Breckinridge’s life and work, drawing on her story to better understand American feminism.

As she pieced together Breckinridge’s story, Jabour said she was fascinated by Breckinridge’s response to the limited professional opportunities available to women during her life. Rather than continue in the male-dominated profession her father had pursued, Breckinridge pioneered a new field—social work—what was friendly to women.

“This discovery prompted me to reexamine my assumptions about ‘feminized’ occupations, especially when I learned that Breckinridge taught what was arguably the first women’s studies class in the United States,” Jabour wrote in the book’s preface. “Who was this woman who persisted despite sex discrimination and transformed gender ghettos into feminist strongholds?”

It wasn’t an easy question to answer. Jabour found a handful of articles about Breckinridge by sociologists or social workers, as well as brief mentions in broader discussions about social reform. But it was nearly impossible to find comprehensive work on Breckinridge’s life.

“I found that, despite her long association with Jane Addams and Progressive reform, books on these subjects routinely omitted Breckinridge—or, if they included her, they misspelled her name,” Jabour wrote.

Jabour dug, though, poring over Breckinridge’s extensive personal papers and correspondence and other treasure troves of information. Her work brought her numerous times to the University of Chicago. (On one such visit four years ago, Jabour even shared some of her findings about Breckinridge’s life and the activist’s two great loves, Marion Talbot, the University of Chicago’s dean of women, and Edith Abbott, the dean of SSA, which Abbott and Breckinridge co-founded).

The story that Jabour's work uncovered was that of a complicated and influential woman. And it was one that shed light on a variety of aspects of women’s activism, including the important roles played by collaboration, personal relationships, and behind-the-scenes research and scholarship.

“For me, Sophonisba Breckinridge's story is really about the power of perseverance and the importance of public service,” Jabour said. “Breckinridge's persistence in the face of obstacles and setbacks not only allowed her to achieve higher education and professional success for herself, but also promoted equality, justice, and opportunity for all Americans. Her combination of determination and inspiration—what she called "passionate patience"—was the key to her absolutely indefatigable fight for social justice on multiple fronts. Her example gives me hope, and I hope it also will give hope to future generations of activists.”