Making of a MOOC

Professor Randal C. Picker was standing in front of the cameras, his black shoes skimming the thick strips of electrical tape stuck to the carpet. This was good.

“On the first day of filming, I moved about eight inches forward,” Picker said, adjusting the argyle sweater his wife had picked out for the shoot. “Now I have a mark.”

He looked up at Andy, a University of Chicago multimedia specialist who was standing behind one of the cameras in the makeshift studio in the University’s Harper Court building. “But right now I’m wondering whether my hand gestures should be muted, if I’m too big for the screen.”

These weren’t things Picker thought about much before he became the first Law School professor to teach a massive open online course, or MOOC, a project that has been as much about testing the boundaries of traditional education as lecturing on the relationship between law and technology. But in the year leading up to the July 13 launch of “Internet Giants: The Law and Economics of Media Platforms”—months in which he took a filmmaking class at Second City, created 1,213 PowerPoint slides, and spent roughly 40 hours in the Harper Court studio—Picker found himself considering movement, props, lighting, color correction, and other things that generally don’t matter during live Law School instruction. His tendency to wander in class, he learned, didn’t work on camera; his talkative hands did.

“Muting your gestures would be terrible,” Andy told him. Picker nodded toward a guest and offered a translation: “Whatever personality I have is in my gestures.” Which seemed to be at least partly true. His hand movements, smooth and effortless, lent a cohesive energy to his monologue. It was as if he already knew his future audience, which would number nearly 3,000 people from 124 countries just three weeks after launch and would continue grow steadily throughout the summer. It was as if they were right there.

“Are we ready?” Andy asked, as Picker, the James Parker Hall Distinguished Service Professor of Law, checked his feet and his microphone. Andy counted down and the other three members of the crew took their places—behind the second camera, on the audio board, and at a table making postproduction notes. That day’s topic, one of seven collections of segments that would make up the final twenty-hour course, was music platforms. But it was May 4, so Picker opened with a Star Wars reference.

“This is a day when Star Wars geeks walk around saying, ‘May the Fourth be with you.’ It’s funny how a particular piece of storytelling takes on this kind of significance,” he said, smiling slightly as he slid from pop culture into the main topic. “But that can’t happen without the platforms for distributing that content.” For the next four minutes—a nice, short, MOOC-friendly chunk—he stuck to his mark as he spoke, pivoting among two cameras and a PowerPoint display before finishing to nods of approval from his team.

As usual, he’d nailed it on the first take.

***

Much in the way that digital platforms have transformed music, video, and publishing, they have changed the ways people learn and scholars teach, and MOOCs are a part of that movement. Unlike traditional university instruction, open online courses are generally free and accessible to anyone with an Internet connection; much of the fervor has stemmed from the vehicle’s potential to democratize education. In the past few years elite universities, eager to throw open their gates in this way, have launched what is essentially a giant pedagogical experiment, partnering with major MOOC providers like edX, a nonprofit startup from Harvard and MIT, and Coursera, the for-profit platform that hosted Picker’s Internet Giants. UChicago has offered five not-for-credit MOOCs, including Picker’s, drawing tens of thousands of participants and contributing to the University’s broader look at digital learning.

Nationwide, the conversation about MOOCs has followed a predictable path, with breathless start-up frenzygiving way to sober dismay that the medium hadn’t yet “disrupted” higher education. But amid the chatter, Picker’s course—and UChicago’s strategy—have deftly advanced the cause, exploring the vehicle’s power not as a digital replacement for face-to-face instruction but as a way to extend, layer, and even scale the academic experience. Picker has been skeptical of both hype (MOOCs will change everything!) and defeatist backlash (MOOCs are over!), preferring instead to act as a patient, curious fact gatherer steering toward an evolving, and increasingly well-informed, goal.

“The MOOC bubble has passed, and we’re at the next stage, doing the hard work,” said Picker, who was appointed in 2013 to the University’s online education committee, which considers faculty proposals for digital courses. Internet Giants wasn’t designed to replace any part of the Law School experience but to test new avenues of learning and to engage alumni in powerful new ways. It is the first UChicago MOOC to be released as an on-demand package rather than rolled out week by week and the first to include an alumni component featuring video chats, discussion groups, extra videos, and a blog available only to UChicago graduates.

“Higher education is evolving, and there is more demand for lifelong learning,” said Mark Nemec, the Dean of the Graham School of Continuing Liberal and Professional Studies, which oversees the alumni piece. “President Zimmer has suggested, and I fully agree, that we’re seeing a potential redefinition of what it means to be a student and an alumnus. And one of the things that might accelerate that redefinition is online learning, which allows teaching to be asynchronous—anywhere and at any time. What it means to be an alumnus is becoming interesting.”

Through MOOCs and other digital platforms, alumni are increasingly able to remain connected to the University, participating in the ever-growing community of ideas from anywhere in the world. The Graham School is working closely with the University’s Alumni Relations and Development office to craft a digital engagement strategy, which has included the exclusive MOOC content and could include future projects, such as bringing alumni together to collaborate on a white paper.

“This is fully understood to be an experiment, although one that is fairly low risk,” Nemec said. “Randy is a very established faculty member with a great reputation, who has a compelling manner and is a very willing partner. He is willing to embrace the spirit of experimentation, the uncertainty, the idea that we’re just trying to learn.”

That was evident in the thoughtful shrug Picker gave when asked to make predictions before the course went live. “I don’t know what’s going to happen,” he said simply. “That’s part of what we’ll find out.”

***

The news, nearly three months later, was good.

By the end of the third week, Internet Giants had reached 2,971 people at varying levels of engagement, from occasional passive viewers to regular participants who were interacting with each other—and with Picker—via social media, discussion boards, and video chats. Enrollment would continue to rise throughout the summer, with roughly 800 new students joining the MOOC each week. (When this story went to press in September, enrollment had hit 7,329. A month later, when this story was posted online, there were 9,353 students from about 153 countries.) There were even a handful of MOOCers who appeared to have completed all twenty hours of material in the first several weeks, perhaps binge watching Picker’s course the way a Netflix subscriber might plow through an entire season of Orange Is the New Black.

“Finishing the binge was psychologically identical to finishing the last episode of the last season of an involving TV show,” a participant with the Twitter handle @drewmmichaels wrote to Picker on July 30.

Picker—who had commented that he wasn’t sure if he’d created something more akin to Citizen Kane, considered by many filmmakers to be the best movie ever made, or Ishtar, a notorious box-office failure—joked that “maybe Breaking Bad should have been the target.”

“A thousand times more cohesive than Ishtar, a thousand times more entertaining than Citizen Kane,” @drewmmichaels assured him.

A participant with the handle @kovacsLLC chimed in: “Agree — it’s a one man tour-de-force. Can we nominate @randypicker for a Webby?”

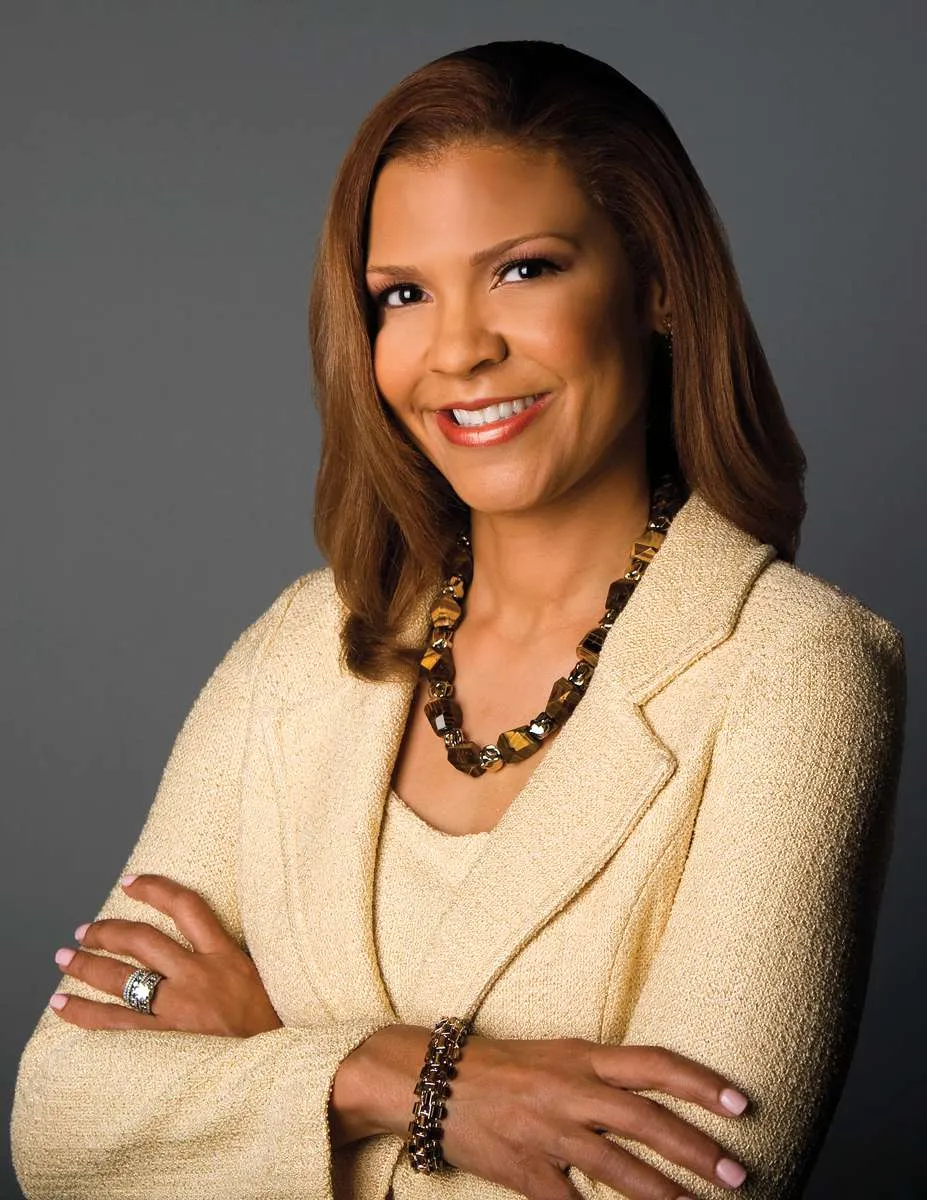

Picker likes to move in the classroom but had to stick to his mark during filming.

Internet Giants also had tremendous global reach, with more than two-thirds of the students coming from outside the United States, from places such as India, China, Brazil, Russia, and Germany. “There are four people in the course from Malta,” Picker marveled in early August. “There are three people from Zambia, there’s two people from the Ivory Coast, I have someone watching from Iraq. The idea that across the planet people are watching this—wow. That’s not bad.”

Alumni engagement was also strong: In the three weeks after Internet Giants launched, about 1,000 UChicago alumni—about one-fifth of them Law School graduates—had registered for the exclusive UChicago extras, and 600 had actively participated in some way.

For Richard B. Leverett, ’10, the course offered an opportunity to finally take a class from Picker, something he hadn’t had a chance to do in law school. Even better, it was directly useful to him as the Director of External Affairs at AT&T Indiana. “This class is right on point with a lot of what’s going on in the industry right now—and things like network theory are relevant to my position,” said Leverett, who has recommended the MOOC to colleagues. “This class has been perfect for me.”

Leverett has devoted about an hour a day to the class, which covers topics such as the debate over network neutrality, the fight over Google Search, the complex legal infrastructure of smartphones and tablets, the US and European Union antitrust cases against Microsoft, and the legal issues that followed the rise of music, video, and publishing platforms. Leverett has participated in the alumni video chats and discussion boards, where he said Picker is able to make jokes that “only alumni would get.”

“To be able to go online and have multiple videos of Professor Picker—it really is like binge watching a Netflix series over and over again. And these topics are just amazing,” he said. “It’s a perfect way to get high-level interaction—and it’s so refreshing to be back in that space a bit.”

Which is exactly the point.

“The idea of taking the residential experience and moving it online so it can be a continuing experience in their lives—that’s what this makes possible,” Picker said. “Is all of residential education going to go away? I don’t think so. But this is something new and different that is also valuable.”

***

Founding President William Rainey Harper could never have predicted the MOOC, but the platform fits his early vision for the University of Chicago. Harper pioneered correspondence education and started what became the first university extension program in the United States.

“The MOOC is completely consistent with that founding vision,” Picker said. “It’s another way we convey ideas and reach out to a larger audience.”

This vision of the MOOC as a complementary layer is a subtle but important distinction that sets UChicago apart from the mainstream conversation about MOOCs, which has focused on accelerating credentials.

“At the University of Chicago we’re not interested in the credentialing potential of online learning—we’re interested in the pedagogical potential,” Nemec said. “This is important because when you have debates about online learning, people are worried about the credential without thinking about this as an instrument. It hasn’t helped that, early on, the rhetoric from the MOOC providers was that they were going to replace the universities. Now, they’ve stepped back, and it’s more about being part of this multichannel approach.”

This is how Picker sees the MOOC, as a third way of teaching, a mode that offers its own distinct advantages. Law School seminars, for instance, focus heavily on class discussion, and Law School courses rely on the Socratic Method of questioning until contradictions are exposed and the heart of a topic or analysis has been revealed. MOOCs, by contrast to both, are primarily lecture based. Participants don’t have many opportunities to engage with classmates during the lecture, and nor do they follow ideas down blind alleys, backing up to figure out where their analysis went wrong. MOOCs, however, do offer students a chance to self-pace, pause and digest, and rewatch intriguing or complicated portions of a lecture. And the discussions that happen on boards and in video chats often involve a wide variety of perspectives and levels of experience.

“The first topic in the course is Microsoft antitrust, and we had people in the discussion who were participants in those cases,” Picker said. “One of the people taking the MOOC was a computer science professor from Utah who had been an expert witness in the case.”

Picker and a small crew filmed the MOOC in a makeshift studio in the University's Harper Court building.

Internet Giants is easy to navigate, laid out in nine sections that include an overview at the beginning, seven modules, and a course review. The modules—for example, “Microsoft: The Desktop v. the Internet,” “Nondiscrimination and Neutrality,” and “Google Emerges”—are divided into lessons, which are further divided into short videos. Participants are able to gauge their understanding of the material by taking three-question practice quizzes at the end of each segment, eight-to-twelve-question graded quizzes at the end of each module, and a seventy-question final exam. Users can access the Picker’s PowerPoint slides, as well as reading lists, sources, and an “Updates and Corrections” section, where Picker is able to share recent changes in the law. He used this in the “Smartphones” module, for instance, to note that a US appeals court had partially overturned a nearly $1 billion jury verdict Apple had won in a patent-infringement case against Samsung over smartphone design—a decision that came down in May, after filming had wrapped.

Students are able to progress linearly through the segments or skip around at will. Meredith Rose, ’13, who took three classes with Picker in law school and now works in tech policy, had limited time, so she zeroed in on segments discussing the history of network industries before pausing to accommodate a particularly busy period at work.

“I like the flexibility and the fact that people can come into MOOCs with different kinds of backgrounds,” said Rose, a staff attorney with Public Knowledge, a nonprofit that promotes an open Internet and access to affordable communications tools. “You can focus on what is new to you, as well as things that are particularly interesting or relevant to where you are.”

Of course, the biggest difference between a live class and a MOOC: scale. Picker, who teaches an average of 104 students per quarter in his Antitrust class, would have to teach that class more than 28 times to reach the same number of students as he did during the first three weeks of Internet Giants. (To be fair, not all of those 3,000 participated fully, but it does help illustrate why the “M” in MOOC stands for “massive.”)

“I had a waiting list of thirty-eight students for my winter Antitrust class,” Picker wrote in July in a guest column on the Volokh Conspiracy blog on the WashingtonPost.com. “But the room holds what the room holds. All that makes education expensive—I say that as a writer of college tuition checks—and intensely local.” Of course, this isn’t an argument against face-to-face instruction; Picker’s hope is that the MOOC engages students who will never go to law school, or who have already been and want to learn something new, or even those who are trying to decide whether to go.

“I talked to a woman today who is a second year at the College who is trying to decide if she’s going to go to law school,” Picker said in May. “She’s going to watch the course over the summer. I would regard a perfect result as her applying to the Law School in two years. I hope when people watch the course they will see what I find exciting about the law. If that makes them all want to go to law school, great. But if instead it just makes them pick up the newspaper the next day and see a story about one of these subjects and say, ‘Oooh, I have to read that,’ that’s good too.”

All of these benefits were among the reasons Picker decided in May 2014 to join the MOOC movement. Over two hours on a Sunday evening, Picker wrote a four-page proposal for Internet Giants, reimagining three of his face-to-face Law School courses—Antitrust, Network Industries, and Copyright—as a whole new course, one geared for a MOOC audience.

There was a learning curve. Picker had to divide ideas into many short chunks—an ideal MOOC segment runs about six to nine minutes—and he had to adjust to being the only one talking. “If I lecture for fifteen minutes during a sixty-five-minute class, that’s a lot,” he said. “And in a seminar, I’m really more of an orchestra conductor.” He also had to engage an audience that didn’t yet exist, and he had to speak in a way that is both accessible and sophisticated, perhaps stopping to define a term like “externality” but not shying away from robust ideas.

“The big change for me was recognizing that I might be talking to people who hadn’t read anything,” he said. “I can count on my students at the Law School to do the reading before class. Here, I explain things more directly and fully.”

***

By early summer, postproduction was in full swing and the launch date was looming.

A University multimedia specialist, on a tight turnaround between filming and release, was working long days editing video. Picker and Reggie Jackson, a UChicago academic technology analyst, were building the final product on Coursera, debating structure and overview language. A small Law School focus group was offering feedback on two different versions of the trailer, one of which would soon be released, and Picker and his production team were exchanging flurries of emails about things like color correction.

“Look at this video—it looks too red to me,” Picker told a visitor one afternoon, pointing to a rough cut of MOOC footage on the computer screen in his office. These were things he noticed now.

By late summer, the MOOC was well underway, enrollment was climbing, and the book-lined set that had been built for Picker was being used to record lectures for faculty from the Biological Sciences Division. Picker, no longer focused on hand gestures and electrical tape, was thinking about his MOOC’s future.

He’d been experimenting with different ways to engage his students, recognizing that there were many valuable ways to participate and that not every way would fit every student’s schedule, interests, and learning style. For instance, he’d recently run an Internet Giants blog exercise in which he’d posted a topic and invited participants to pick a side and argue. Picker received 35 responses to that, and he planned to use the discussion as the basis for an additional video. He had also taught a version of Internet Giants live to visiting international scholars who were part of the Law School’s Summer Institute in Law and Economics, some of whom participated in the MOOC as well.

Now, rather than focusing on a second online course, he was adding more layers to Internet Giants, continuing the test the MOOC’s engagement potential. The segments, by themselves, are like a video textbook, he said—the real power comes from the discussions and interactions that grow out of them. Figuring out which pieces best achieve that is part of the experiment.

“How do you turn a video book into an ideas community? I don’t want you to read the book and be done,” he said. “How do I bring the next 3,000 students in, and for the people who are already here, what is the next part of our process together?”

That week, he tacked on a bonus module titled Internet Giants: Experimental. He had three ideas in mind: an online reading group on topics related to the MOOC, a series of podcasts, and additional video chats on Google Hangouts. He launched the book group first with a discussion of BlackBerry’s demise, offering up a list of suggested readings that included the 2015 book by Jacquie McNish and Sean Silcoff, Losing the Signal: The Untold Story Behind the Extraordinary Rise and Spectacular Fall of BlackBerry. The group planned to discuss the readings online, with a video commentary and video chat at the end of August. Down the road, he said, video chats might function as small workshops, and podcasts might feature Picker in a dialog about topics related to Internet Giants.

As it had been from the beginning, the process was still one of curiosity and discovery. But it was also one that had already succeeded in its central mission: to bring people together to share, learn, and celebrate new ideas.

“The University of Chicago is the most exciting intellectual community on the planet, and we want to capture that,” he said. “I am excited that people who have responded the MOOC most directly love the material and see what I love about the material—that is incredibly gratifying.”