Lifting the Curtain: Futterman Reflects on the Aftermath of the Laquan McDonald Crisis—and What It Tells Us about How Change Gets Made

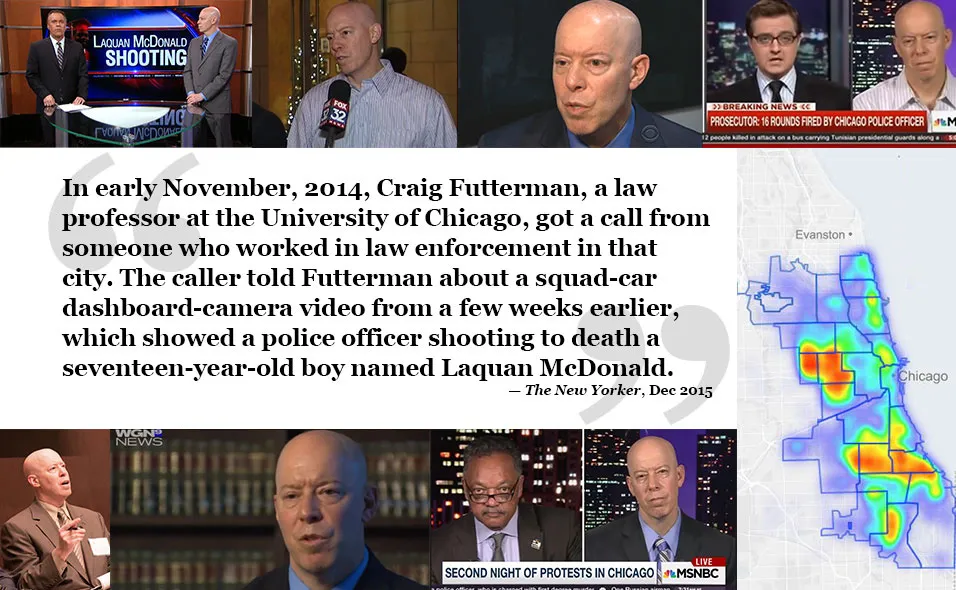

Just after Thanksgiving, as Chicago was erupting in outrage over dashcam footage of a white police officer fatally shooting a black teenager, Clinical Professor Craig Futterman felt the first rumbles of a shift he’d been imagining most of his career. It was the beginning of what would become one of the busiest and most extraordinary periods of his professional life—and one that marked significant progress in Chicago’s struggle to address issues of race, justice, and policing.

It would also become a lesson in how change gets made, and how the work of the Law School’s clinics can reach far beyond the lives of their clients.

Futterman and his students had spent nearly a year engaged in litigation before convincing a judge last November to make the video public, and they expected at least some anger after its release. It was an obvious response to a horrifying scene: Chicago Police Officer Jason Van Dyke shooting a retreating 17-year-old Laquan McDonald and then continuing to pump bullets into him as he lay on the ground—a striking contradiction to the official police department version that had Van Dyke acting in self-defense. But this wasn’t Futterman’s first go-round exposing injustice—he had racked up an impressive list of courtroom victories in his 16 years as director of the Law School’s Civil Rights and Police Accountability Clinic—and he knew that public indignation could be fleeting, that broad-scale change often requires a bucketful of wins before it reaches a tipping point. On some level, he had braced himself for the inevitable fade-away from public concern.

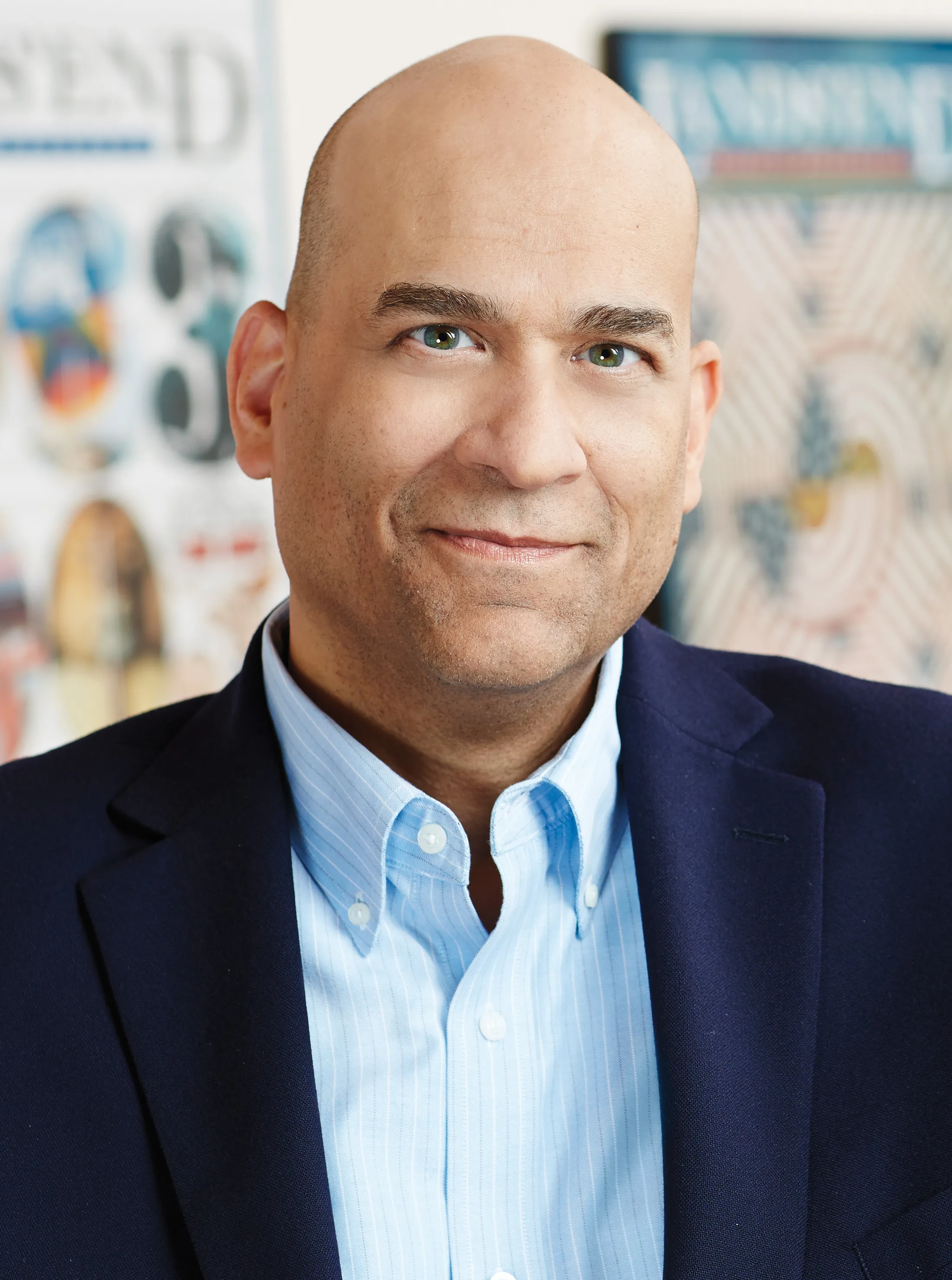

Futterman talks to Ayla Syed, '18, a student in the Civil Rights and Police Accountability Clinic, outside the Law School's Arthur O. Kane Center for Clinical Legal Education.

“I had several fears right before the video was released,” Futterman said, sitting in his office surrounded by evidence of the whirlwind he had helped create: newspapers, research, proposed legislation, and drafts of a paper he was writing about law enforcement policy reform. It was late February, and although he was still too busy—and, frankly, too exhausted—to fully process the events of the previous three months, his mind was abuzz with the insights of fresh experience.

“I think my biggest fear,” he said of those days right before the November 24, 2015, release, “was that people wouldn’t care.”

As much of the nation now knows, people cared. The video sparked protests, a wide-ranging federal civil rights investigation, and a pledge by Mayor Rahm Emanuel to reform the Chicago Police Department. The police chief lost his job, Van Dyke was charged with first-degree murder, and in the March primaries, the county’s top prosecutor—who didn’t charge Van Dyke until the day the video was released, more than a year after McDonald’s death—was voted out of office. Emanuel also created a police accountability task force—which is chaired by former prosecutor Lori Lightfoot, ’89, and includes Clinical Professor Randolph Stone—and appointed Sharon Fairley, ’06, to lead and restructure Chicago’s Independent Police Review Authority, a city agency that investigates complaints of police misconduct. Suddenly, Futterman and his partners at the Invisible Institute, who had already drawn media attention earlier in November when they jointly released a first-of-its-kind, searchable database of Chicago police misconduct complaints, were flooded with media requests from all over the world. Lawmakers called. Even the White House sought Futterman’s insights on criminal justice policy. It would be many weeks before Futterman, who was still teaching and running the clinic, managed to get a full night’s sleep. He had helped trigger an awakening.

And that awakening was notable not just for its scope and intensity, but for its focus. For the first time, everyone was talking about the underlying realities that had been the core of Futterman’s message for years: the “code of silence” among police officers that had protected Van Dyke, the need for transparency and accountability to stem a persistent pattern of police abuse, and the fraught day-to-day interactions between minority youth and law enforcement.

“It was as if a curtain were lifted, and suddenly, there was this simple truth that we all knew: Yes, the code of silence exists in Chicago. Yes, there are real and systemic problems of police abuse here in Chicago,” Futterman said. “It wasn’t just that folks had to come to grips with this horrific shooting. While Officer Van Dyke’s callous acts were truly extraordinary, I think what really struck people was seeing how normal it was for every single officer on the scene to circle the wagons and cover up what Van Dyke did. That the life of a 17-year-old kid mattered less than covering for a fellow officer.”

The signs that people had grasped the bigger picture were evident to Futterman within days of the release.

“I think it first struck me on Black Friday,” Futterman said. “There were all these protests, and the business owners on Michigan Avenue were reacting; their sales were being hurt on the single greatest shopping day of the year. There was a real economic hit. But some of them—many of them wealthy, many of them privileged—said they supported the protesters. They directed their comments at the power structure, at our leaders. It wasn’t, ‘Get these protesters away from our stores, you have to arrest them all.’ It was, ‘You have to do something about the problem, about the reason these protesters are out here.’ Those store owners got it.”

Nearly two weeks later, Futterman was again buoyed when Emanuel—himself the target of criticism over the delay in releasing the video— made an emotional speech that directly addressed systemic failures.

“For the very first time in my life, and the first time in this city’s history, our leaders—our mayor himself—acknowledged very poignantly that a code of silence exists, and that it is not merely a relic of the past,” Futterman said. “This is the very first time I’ve seen our leaders speak in the present tense and say that, yes, we have real systemic, pervasive problems when it comes race, racism, police abuse, and the code of silence in Chicago. And that, to me, is a transformative moment.”

But it hadn’t happened in isolation. Futterman and others around the country had been chipping away at these issues for years, adding drop after drop to the bucket, even when it seemed as though it would never tip. When the Laquan McDonald video was released, the country was already engaged in conversations about race and policing following the deaths of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and Freddie Gray—all black men who had been killed during encounters with white officers. The previous spring, Futterman and his partner at the Invisible Institute, independent journalist Jamie Kalven, had drawn more than 300 people to an emotional two-day conference at the Law School that brought together urban youth, law enforcement officials, prominent advocates, and top scholars to address the relationship between police and their communities. And in early November—just as Futterman and Kalven were releasing their database of police misconduct complaints and shortly after FBI Director James B. Comey, '85, visited the Law School to talk about race and police—the University of Chicago Legal Forum had advanced the conversation further with an academic conference on police accountability.

“There’s an analogy to mountain climbing,” Futterman said. “At certain points, if you look up the mountain, it feels insurmountable. So you just take the step that’s right in front of you. And you keep taking these steps, and then suddenly you find yourself on top of that mountain. I’m not sure if that’s where we are, and maybe there are lots of different mountains, but right now we have so many opportunities for meaningful reform. They involve many different things that we’ve been working on for years, and it is all happening at the same time.”

The rest of the story, of course, has yet to unfold. But Futterman is heartened—and not at all surprised—to see members of the Law School community, including Fairley, Lightfoot, and Stone, at the forefront. “The University of Chicago provides an outstanding education, and working in the clinic enhances their humanity,” he said. “That humanity, depth of thought, and care—those are the necessary qualities to promote justice.”

Futterman has repeatedly noted that he has tremendous respect for police and believes that the vast majority welcome reform and want to strengthen their relationship with the community. Most police officers have not been accused of misconduct; the code of silence, Futterman has said, is a professional norm with which they must cope.

But now the opportunity to change is right in front of everyone. It feels mostly the way he’d imagined it, too: an awakening that advances a much larger and evolving movement.

“I imagined it beginning with the truth,” he said. “One of things that had been standing in the way of change had been lack of knowledge. The vast majority of us didn’t know about the conditions of impunity in our own backyards, the reality of police abuse and unequal justice. Now we know, now we’re aware, and more people are becoming aware. I don’t want to think about this as just one moment; it is a part of the larger process of change. We are all being forced to reckon with the realities. And now it’s up to all of us what we do with that knowledge.”