Exploring a River of Ideas with the Clinical Faculty

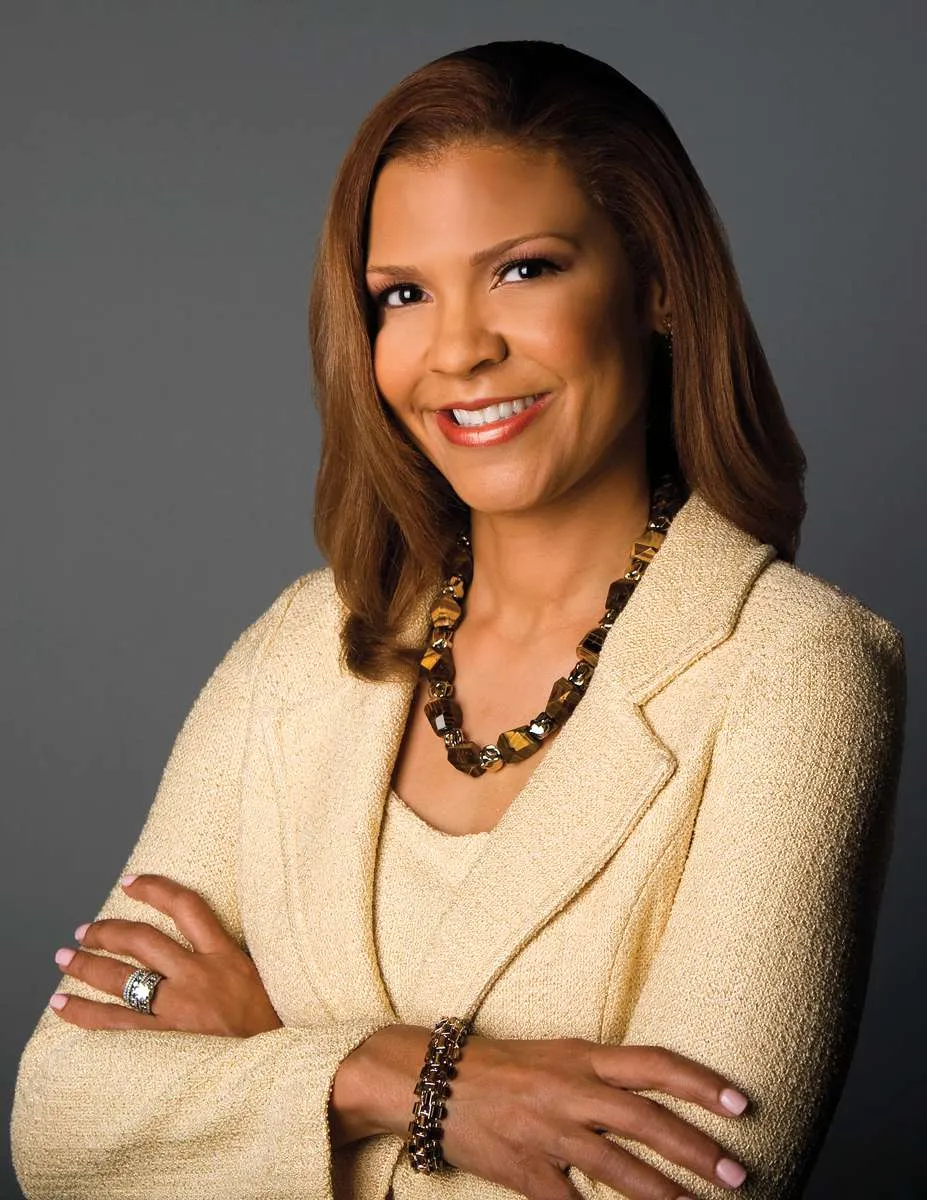

Herschella Conyers looked intrigued.

But beyond that, the clinical professor betrayed no emotion—not pride or annoyance or delight, just the patient, measured visage of a woman who has seen a thing or two and knows the value in letting a conversation play out unjudged. She simply listened as the fourteen Law School students in her Life in the Law seminar batted about various hot-button topics—at that moment, it was the ethics of human cloning—jumping in only to offer nuance, challenge assumptions, or prod the conversation in novel directions.

“Why the repugnance?” she asked as words like “Frankenstein” and “unnatural” and “playing God” filtered into the discussion, which had expanded to include abortion, stem cell research, and the destruction of unwanted frozen embryos. The room was buoyant and respectful even though many of the comments were bathed in swells of emotion or tinged with religious conviction.

Conyers paused.

“What is it to be human anyway?” This was the real question, or one of them. And in many ways it’s the reason the longtime defense lawyer and director of the Law School’s Criminal and Juvenile Justice Clinic teaches a class that, at first glance, appears removed from her usual work. Conyers is one of several Law School clinicians who do this, stretching beyond their core expertise to teach topics that interest them. Clinical Professor Randall D. Schmidt, the Director of the Employment Discrimination Project, teaches Admiralty Law, for instance, and Assistant Clinical Professor Mark Templeton, Director of the Abrams Environmental Law Clinic, last spring taught a two-day session on nonprofit leadership as part of the UChicago-led Civic Leadership Academy.

But in each case, these seemingly disparate endeavors have meaningful connections to, or even have grown from, the clinicians’ core work. They don’t merely illustrate diverse passions and talents, they stand in tribute to the choose-your-own-adventure nature of true intellectual exploration, monuments to the far-flung places that a set of ideas can take you. Admiralty law, for instance, offers new ways to think about workers’ rights—there are special remedies for injured seamen that don’t exist in land-based employment law, and this has always been part of the draw for Schmidt. Conyers has long been struck by the complex meaning-of-life questions that ripple through so many aspects of criminal law. And Templeton’s Civic Leadership Academy experience was infused with the same themes that have trickled into nearly every corner of his diverse career—his desire to effect change, his willingness to tackle big issues, and his ability to understand and manage risk.

“The University of Chicago Law School has this broad understanding of how we can have an impact—it allows and encourages us to engage in these kinds of opportunities,” said Templeton, whose career has included nonprofit, government, consulting, and higher education work.

This openness, imbued so thoroughly into the culture of the Law School, serves as a powerful backdrop for many endeavors; it’s all part of the common understanding that there are infinite tributaries to explore in the pursuit of knowledge and understanding.

The popular story about why Schmidt teaches Admiralty is that he’s an avid mariner.

And indeed he is: he and his wife own a forty-two-foot sport fishing vessel and recently spent a year, on and off, cruising down the river system to Mobile, Alabama, out to Key West and then up the East Coast to New York City before taking the Hudson River to the Erie Canal and then navigating back to Chicago via the Great Lakes. But the hobby isn’t really why he began teaching the class fifteen years ago.

“The myth is that the Law School asked me to teach Admiralty because I’m the only faculty member with a boat,” he said, laughing. “I don’t disabuse my students of that myth, but it’s not true. I do have a boat, but I said I’d teach Admiralty because I was interested in jurisdictional issues and the rights of seamen and injured workers.”

Admiralty law, he explained, is a complex and often difficult area that is rooted in centuries-old sea code and contains a mix of federal and state law, as well as federal common law that doesn’t exist on land. What’s more, maritime law often contradicts land-based rules.

“Even very experienced judges and lawyers, because they don’t take the time to really understand admiralty, get it wrong,” Schmidt said. “Judges describe this as one of the most difficult areas of law.”

In Conyers' Life in the Law seminar, students discuss issues such as abortion, capital punishment, cloning, and assisted suicide.

Early in the quarter, students tend to view cases through a land-based lens, and Schmidt needs to push them to think in admiralty terms. “They’ll say, ‘This is what I learned in Torts,’ but that doesn’t necessarily apply in Admiralty,” Schmidt said. “And that’s where a lot of the class discussion is focused.”

The cases that provoke the most discussion are often centered on seamen’s rights. In addition to the fascinating complexity, there’s a deeply human piece that Schmidt works to impart to his students.

“Sometimes seamen do very stupid things,” he said. “The myths we hear about the bad habits of seamen are too often true. But the law protects them from their ‘bad habits.’ Whether they are falling from a balcony because they’ve had too much to drink on shore leave or they are injured doing very dangerous work in terrible conditions on the high seas, the law protects them, at least up to a point.”

For Schmidt, teaching Admiralty keeps him connected to other areas of the law outside employment. “More than anything,” he said, “it keeps the intellectual curiosity going.”

For Templeton—who has served as the executive director for the Office of the Independent Trustees of the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill Trust and worked at Missouri’s Department of Natural Resources, the US Department of State, and McKinsey & Company, among other places—the Civic Leadership Academy offered a chance to use his broad experience to help a variety of midcareer professionals move in new directions.

The leadership development program, which was created in part by the University’s Office of Civic Engagement, gave twenty-eight rising professionals from nonprofit organizations and local government agencies the opportunity to hone skills in civic innovation, human capital, strategy and management, data analytics, financial planning, and strategic communications over the course of ten, two-day modules that ran from January to June. Templeton’s session—which he taught in April with Darren Reisberg, Secretary of the University, and Brian Fabes, CEO of Civic Consulting Alliance—examined the roles of top nonprofit leaders in achieving great missions while managing risks. It was called Leading Boldly, without Sinking the Ship.

“I think it is important that the University is engaging with these people and offering some of our experiences and ideas to try to bring about positive change in Chicago,” Templeton said. The students included, among others, the operations director for Austin Coming Together, a group dedicated to improving education and economic development in Chicago’s Austin neighborhood, officials with the Cook Country Forest Preserve and Cook County Health System, and the pastor of a North Side church.

“These were midcareer professionals, and they’re at a different point—a lot of them could apply what they learned immediately,” Templeton said. Many of the participants were working through very specific issues, and Templeton enjoyed the challenge of helping them think strategically. The pastor, for instance, had an enviable puzzle: the church had, somewhat unexpectedly, reaped a large return from an investment—and the leadership needed to figure out the most effective way to spend the money. Should they use it to improve the building? To start a new program?

“They decided to share the good fortune with parishioners, who then used the money to effect good deeds themselves,” he said. “I never would have thought of this—and that’s what was fun.”

Clinical Professor Mark Templeton taught a two-day seminar on nonprofit leadership to 28 rising professionals as part of the University's Civic Leadership Academy.

In this way, the work tapped into the same challenges that drew Templeton to his work on the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill, when he was tasked with ensuring that BP met its cleanup commitments, and to the Law School’s Environmental Law Clinic. It has all been about weighing and thinking through big ideas, often balancing risk with the need to act boldly.

“What is the right balance between protecting the environment and the use of natural resources? What are the incentives? What are the appropriate accountability mechanisms?” he said. “These are timeless questions.”

Conyers’ questions are timeless, too. These are issues she’s thought about as a defense lawyer and clinical professor for years. After all, criminal law is rife with discord rooted in the emotional complexity of how one defines and values human life.

“It has always struck me that the people who oppose abortion say, ‘it’s a human life’ and the people who oppose the death penalty say, ‘it’s a human life’—they use the same language and rhetoric,” she said. “So you would think those two contingencies would come together, but they rarely do. I think life means something different depending on who’s saying it. So that made me think: how do we think about life in legal terms, and in the law?”

Abortion and capital punishment bookend her Life in the Law class, which Conyers has taught for four years, with right-to-die, assisted suicide, cloning, and other reproductive issues filling out the middle. Students explore how definitions and valuations of life play out in the law, reading cases, discussing policy making, and debating the impact of social, medical, and religious values in legal analysis. Conyers pushes the students to think past their own beliefs and politics. She pushes them, too, to think about life in terms of race and gender—sometimes difficult areas, but ones Conyers thinks are important to explore.

“People operate under assumptions that we don’t even know we’re operating under,” she said, adding that it’s particularly important for future lawyers to confront the underlying beliefs and assumptions they bring to the table. People tend to compartmentalize, and they often believe that their personal views don’t impact their work—but that’s often wrong, she said.

The course’s title, for this reason, has a bit of a double meaning: it is both about how life is viewed and valued in laws, policies, and court cases and about how one navigates the intellectual waters of life as a lawyer. Conyers works hard to remain neutral as the students unpack emotionally fraught concepts.

“For me, the most damning thing that happens in a classroom is you say, ‘no judgment’ and then everything you do exudes judgment,” she said. “So when I say, ‘no judgment,’ I then have to work on it to make sure there’s no judgment.”

The exercise in nonjudgment gives Conyers a chance to check in with herself, to examine her own underlying beliefs. And, as with Templeton and Schmidt, her class has given her a chance to connect ideas in a different way—and to teach students to do the same.

“I hope they will live their lives as lawyers with integrity and thoughtfulness and leadership,” Conyers said of her students. “Being a lawyer shouldn’t be just a job, it should be a worldview about how to have impact.”