'Your Education as a Learned Professional Does Not End Today'

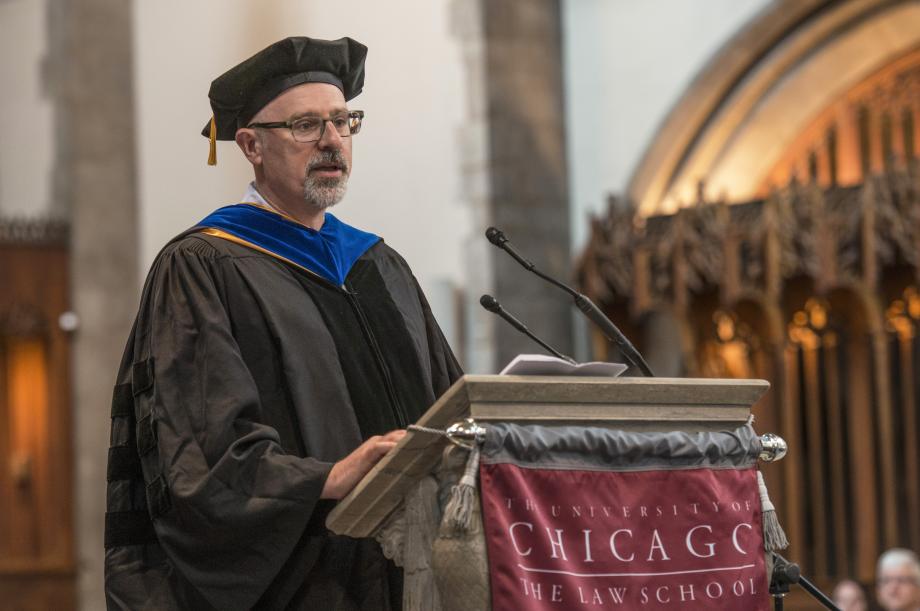

Professor Ginsburg Addresses the Law School Class of 2018

Class of 2018, families, and friends, it is a tremendous honor for me and for all of the faculty to be here to join you on this momentous day. We call it commencement for a reason, for today after many years of schooling, you commence your professional careers and enter the learned profession of law. The phrase learned profession is a bit old-fashioned, but I’d like to spend a few minutes talking about it, because I think it is of tremendous importance in our current moment and for our democracy.

Let us start with the learned. All professions by definition involve the application of specialized knowledge to particular problems, and so they must be learned. Learning the law, in particular, is very much like learning a foreign language, in part because we lawyers we apply novel meanings to ordinary words. Venue is not just where you go to see a concert, a tort is not just an excellent Austrian cake, and a party is not just where you are going after graduation. Franz Kafka captured this when he noted that a lawyer is the only kind of person who can write 10,000-word document and call it a “brief.” Besides learning new meanings for old words, you’ve also learned new words, like curtilage, demurrer, joinder, and estoppel; if nothing else your Scrabble skills have advanced in these three years. And of course you now can impress your friends and family with Latin phrases ad infinitum, including res ipsa loquitor, mens rea, de novo, de jure, and de minimis. And if some of you are getting nervous right now because you don’t recognize all of these terms, don’t worry, because you’ll spend the next six weeks in bar review class learning them all over again. That brings me to another term you need to assign a new meaning to: bar review. Unbeknownst to many of you until now, this refers to an intensive period of study before the bar exam.

Those of you who have actually studied a foreign language know that there is a steep learning curve. At first you are excited by all the new terms. Slowly, haltingly, you begin to put words and phrases together, you struggle with the new grammar and vocabulary, you have plateaus and breakthroughs, but you advance and then, one day, eventually, you are ready to go out and walk the streets of a foreign city, to communicate with taxi drivers and street vendors, and it is here that the real learning happens.

Today is that day. You’ve spent three years learning a new language and are ready to go out into the world to try it out. In doing so, you will find that you know a lot of things, but there is also much more that you don’t. And you will need to continue to learn. As the Chinese sage Confucius observed 2500 years ago, "The essence of knowledge is, if you have it, to apply it; and if you do not have it, to confess your ignorance.”

Part of being a professional is to admit what you don’t know and to be responsible for your own continuing education. By this I don’t mean the bar-mandated Continuing Legal Education classes, though I do recommend that you attend these in accordance with the rules of your jurisdiction. I mean that you are now the designer of your own curriculum. You can choose what to read, who to listen to, who to ignore, and what skills to acquire. Discernment and judgment about these things are particularly important in our era, in which we are drowning in information and data. There is a kind of ethics of sorting through information in our era, an ethics not taught in the MPRE class. We did not teach you much about it, because no one does. But the ethics of sorting and acquiring information is essential for your continued education and may be relevant for the quality of our shared democratic future.

The legal profession, it has long been observed, has a special relationship with democracy. Tocqueville saw the profession as an American aristocracy, a keeper of civic virtue, and an important safeguard against the tyranny of the majority. His observation that scarcely any issue arises in the United States that does not end up in the courts is even truer now than it was in his day. This means that you all have just acquired not only a degree, but an extraordinary amount of social power. And you are graduating at an extraordinary time in which to use it.

The words used to describe our moment are all very familiar: we are swimming in outrage, polarization, and mutual distrust. There is widespread concern for our civic discourse and even for the health of our democracy. But the moment is also one of great opportunity, for mobilization, articulation, and recommitment to our highest ideals of a learned profession in service of democracy.

Democracy should not be taken for granted, and to highlight the point I want to note that today, June 9, is the anniversary of two events, both relatively obscure to us now, that are separated by more than 2400 years. On this very day, in 411 BC, one of the world’s earliest democratic experiments in Athens was overthrown when a group of wealthy citizens established an oligarchy, the Council of 400. Like many oligarchies, the leaders fought among themselves and the regime did not last, but it did disrupt Athenian governance for the better part of a decade until democracy was fully restored.

Today is also the anniversary of the date in 1954 when at a televised hearing in the Senate, Army lawyer Joseph N. Welch asked Senator Joseph McCarthy a famous rhetorical question, “Senator, you've done enough. Have you no sense of decency, sir? At long last, have you left no sense of decency?” This exchange marked a major turning point in the downfall of Senator McCarthy and his chief counsel Roy Cohn, a man ultimately disbarred years later for ethical violations.

Welch’s story shows us shows the power of a lawyer, not in filing a motion or winning a case, but in speaking a simple truth at a time of great peril. It reminds us that professional ethics entails much more than simply following the relevant bar rules of the jurisdiction. It is not merely about avoiding comingling client funds or keeping communications confidential. It extends beyond acting in a traditional legal capacity. It involves acting with integrity, taking on an unpopular client or cause, saying no when a client asks you to do something you cannot, and treating adversaries with respect. It involves demanding decency, in public and in private. Each time you do one of these things, you act as an ethical professional. Each of these individual acts may be small, but in sum, repeated over the course of your career, they not only preserve the integrity of the profession, they protect the rule of law and democracy itself.

As you go forth as learned professionals in this extraordinary time of challenge and opportunity, I’d like to suggest that some of the values of the University may be valuable touchstones in this regard. Now I know that we talk a lot about our values at the University of Chicago. We have to admit that, like the country as a whole, we do not always realize those values perfectly, but this does not render them any less important or valid.

The first value is that of rigorous and vigorous questioning of ideas. We talk a lot about how vigorous debate helps to get to the truth, and this is valuable and good. But debate has another quality that is particularly important in our era. When you debate to learn, your opponent becomes not just an adversary to be defeated, but a source of potential information. And it can even be a source of empathy. As you fight in the courtroom or across the table over the contract terms, you would do well to try to see your opponent’s point of view. Indeed, this will make you a more effective advocate for your own side.

Debate also requires rules to structure it, and norms of mutual respect. As a lawyer, you fight zealously for your client, but at the end of the day, you may lose some cases or causes. When you lose, you don’t seek to overturn the rules which help to make the contest work, just as when you win you don’t demonize your opponent, but treat them with professional respect.

A second value of the University is the great Midwestern virtue of hard work. We like to think the University of Chicago is no longer the place where fun goes to die. That’s why I had to explain to you the other meaning of the term bar review. But the University is a place where we do work hard. Each of you has put in countless hours, and standing here today each of you has proven yourself to be in the 99.9th percentile of work ethic. This is a value that serves you well whatever you do. Some of you will go out and do mergers and acquisitions, others will be working on immigration cases or working for a federal judge, and some of you will return to your home countries to practice law. Some of you will be outside the law entirely. But all of you will be Chicago law school graduates, with the values of working hard for what you believe in and as professionals.

The third value is the importance of integrating ideas and practice. The law is called a learned profession because it is both a practical skill, but also grounded in ideas. You need both to be effective. Justice, the rule of law, equality, and even decency are all abstract concepts that only come to life through the everyday engagement of lawyers, who put the ideals into practice in their actions. I think the task of a lawyer in this regard is similar to that of a citizen in a democracy and was best summed up by a nonlawyer, Shirley Chisholm, the first African-American woman ever elected to the US Congress and the first woman ever to run for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination. She said, “You don't make progress by standing on the sidelines, whimpering and complaining. You make progress by implementing ideas.” I love that.

Today, you leave the University with the tools to go out and implement ideas. Your education as a learned professional does not end today, but you will set your own path in your education from this point forward. You have the work ethic and the values to do so. And you speak the local language. And, finally, if there is ever a time you get lost along the way, just remember to follow the Maroonbook road. Thank you, and congratulations to the Class of 2018!