Serving the Client Who Often Looks Like You: What it’s Like to Practice Criminal Defense as a Minority

Being a criminal defense lawyer and a person of color means many things in practice, according to a panel devoted to the topic at the Law School on January 9. It means that systemic bias against minorities is in play against both you and your client. It means you have a special relationship to your client, despite your drastically different circumstances. And it means that your work is inherently personal and tied to both your professional and racial identities.

The panel, “Practicing Criminal Defense as a Person of Color in the Age of Mass Incarceration,” examined the interplay between a minority lawyer’s professional mission and his or her personal emotions about race and justice. Panelists were Gwendolyn Anderson, a veteran criminal defense lawyer now in private practice; Chastidy Burns, Assistant Public Defender for Cook County; Clinical Professor Herschella Conyers of the Criminal and Juvenile Justice Project; and David Owens, Lecturer in Law and Staff Attorney in the Clinic’s Exoneration Project.

They spoke about the challenges and rewards of representing defendants who are more often than not minorities, just like them. In 2012, black males were six times as likely and Hispanic males were 2.5 times as likely to be imprisoned than white males, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. The disparity was even higher for black males ages 18 and 19, who were almost 9.5 times as likely to be in prison as white males of the same age.

“There is something about looking at a client, and thinking…that could be my husband. That could be my father,” Conyers said. As you age, it becomes, “that could be my son. That could be my grandchild.”

Conyers pointed out that, while plenty of white attorneys work very hard for racial equality, she feels a special calling at least in part because she is black. “The system has not gotten better. It has not gotten more just. As a black woman, I feel the urge to keep the fight going.”

Burns remembered that when she first started interning for the public defender she “had no idea almost all the clients would be African-American men. I realized a lot of them come from similar backgrounds, and the reasons they ended up in a courtroom were not always what they seemed.”

Owens said he wanted to address, through law practice, some of the problems he faced growing up as a black child. He was strip-searched as a middle-school student, for example, because he took something from a store’s sidewalk sale into the store. He was once questioned about stealing his own bike, and he has been pulled over while driving multiple times without just cause.

All this frustration could mean “you could hit the streets,” Owens said. “I chose to hit the books and try to take that power back.”

Anderson talked about working in the late 1970s as an assistant public defender in Cook County, in the felony trial division. She never saw any other black women in her role in the courthouse at 26th Street and California Avenue, she said. She told of hearing police beating her clients into confessions.

The attorneys said that while they have had moments where they’ve felt discounted or taken less seriously because of their race, they also find that minority populations trust them more, and that they can work and socialize in their clients’ communities without suspicion.

When you do feel discriminated against as a black attorney, “you have to immediately get over it,” Owens said. “Because I’m not there for myself, to fight some big racial issue with the judge. I’m there for my client.”

The attorneys also talked about how increased media coverage of violence in Chicago has only made their jobs harder. Lawmakers who want to look tough on crime enact measures that are even harsher than the already overly punitive laws on the books, Conyers said. And judges are afraid to show mercy to someone who might later commit a high-profile crime.

Despite those frustrations, the big payoff of being a public defender, Anderson said, is that it teaches you how to be a true litigator. You’re often working with a very tough set of facts, and you still have to be the best possible advocate. “You really learn how to try a case,” she said. “Being a public defender, I got the chance to try every type of case under the sun.”

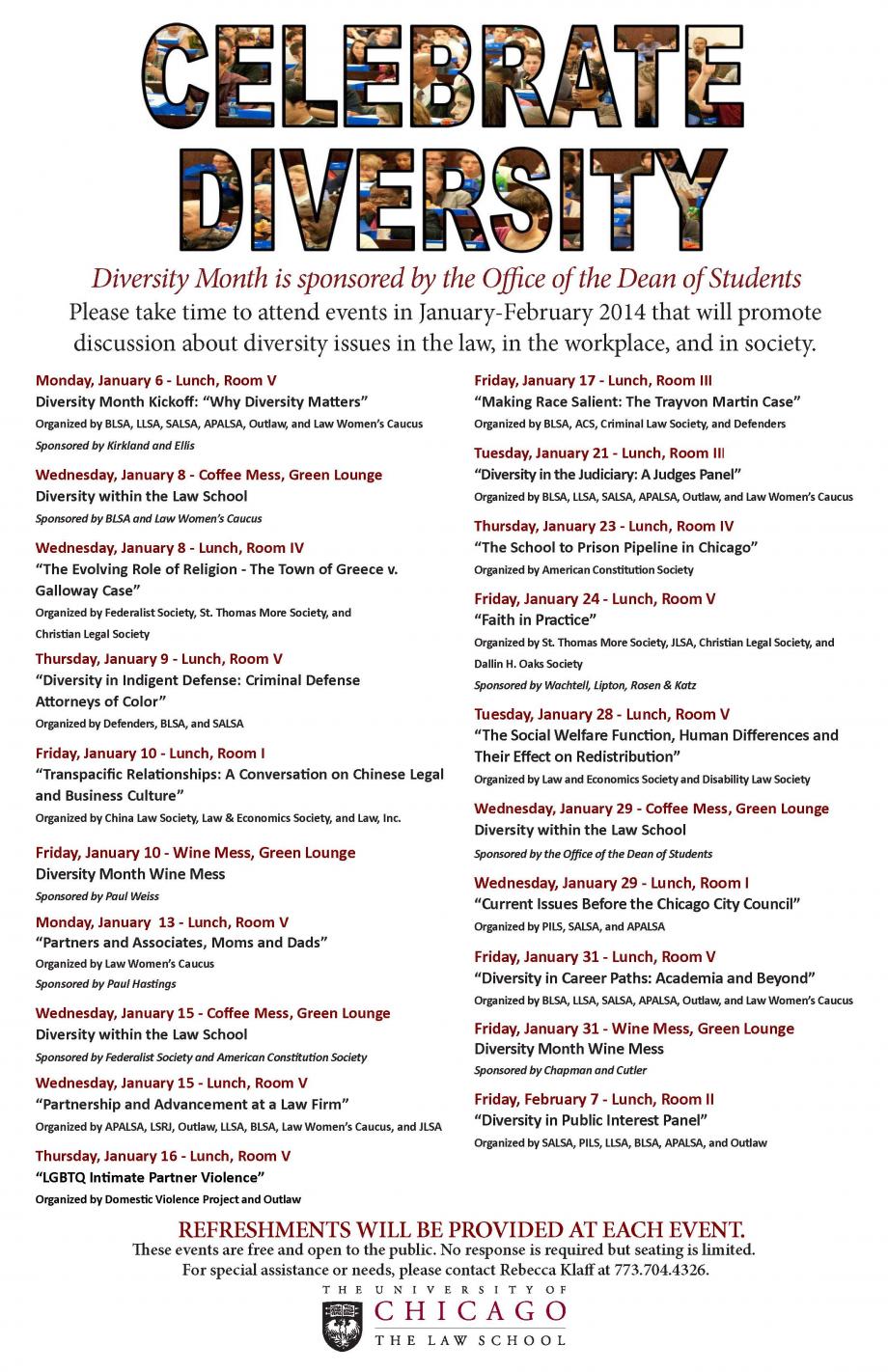

The panel was sponsored by the Black Law Students Association, the South Asian Law Students Association, and Defenders. BLSA member Matthew Wissa, ’16, served as moderator. The event was one of many offered in January as part of Diversity Month at the Law School, presented by the Office of the Dean of Students; the full schedule is linked under the image at the top right.

Wissa, the moderator, said the panel allowed students to gain “a glimpse of the realities in our criminal justice system. If we are not aware of the shortcomings and difficulties of the system, we cannot begin to address them.”