Memories of Nuremberg

Throwback Thursday is a regular feature offering glimpses into the Law School’s rich history. This is our second installment.

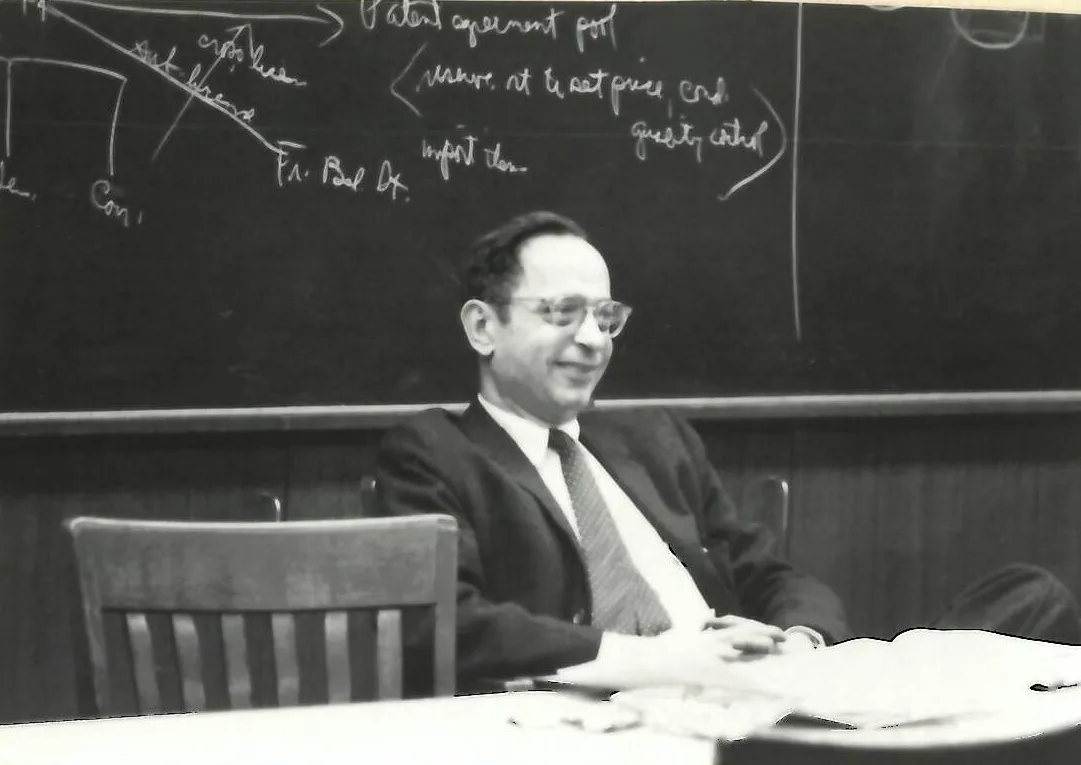

When Bernard D. Meltzer, ’37, was invited to join the prosecution staff of the Nuremberg War Trials in 1946, he sensed that it would be a challenging and grim experience.

“But initially, at least, I did not grasp that it would be considered perhaps the greatest trial in history,” he later wrote. He was aware of the Nazi persecution of Jews and others, and he knew that it had led to tremendous losses of life, spirit, and property, but the full scope of the Holocaust was not yet apparent. That knowledge would emerge — and settle in to the permanent place in his consciousness — later.

Meltzer, an Edward H. Levi Distinguished Service professor who joined the Law School faculty after Nuremberg and retired in 1985, had worked at the Securities and Exchange Commission and the State Department and had helped draft the United Nations Charter.

He was originally assigned to the economics case, leading a team of lawyers in prosecuting business executives who had helped finance the Nazis and those who were responsible for and had profited from slave labor. Later, he was also asked to take on the concentration camp case.

“We had 10 days to prepare for that case, a case which was a symbol of the Nazi regime,” he said in a 2006 interview with the Chicago Bar Association Record. “I wrote as quickly as I could and slept as little as I could. The evidence was a lawyer’s dream and a humanist’s nightmare.”

He was struck by the Nazi’s methodical record keeping, which included concentration camp totenbuchs, or “death books.”

“I was most interested in the German predisposition to write things down,” he later said. “For them it was more important to worry about making the record than what was contained in the record.”

In the books, deaths at the Mauthausen camp were recorded in alphabetical order, two minutes apart, with the cause listed as “heart disease.”

“I still recall the hush in the courtroom when those books were put into evidence,” he wrote in a personal memoir, Bits and Pieces About My Professional Work.

He also recounted seeing the surviving major leaders of the Nazi regime in court:

“Seeing them in the dock, stripped of their medals and insignia of power, one could scarcely believe that these men had dominated much of the world and had terrified most of it.”

Meltzer also conducted the pre-trial interrogation of Hermann Goering, German air force chief and the highest-ranking Nazi tried at Nuremberg.

“Of those I met face to face, Goering was the most interesting, and most diabolical,” Meltzer wrote. “He was intellectually quick, verbally nimble, and always wily. He often sensed the ultimate purpose of a question as soon as I posed it. Goering was completely unrepentant and glorified his role as second to Hitler and the first of the named defendants. He assumed responsibility for defending the Nazi regime while attacking the laws of war as obsolete.”

Meltzer also prepared the case against Walther Funk, the German minister of economics and president of the Reischsbank, which had become the storehouse for gold fillings, jewelry, and other valuables stolen from dead concentration camp victims.

“By trial time, he was in poor health; he wept frequently as evidence of Nazi horrors piled up,” Meltzer said of Funk.

Meltzer, the son of Russian Jewish immigrants, was often asked after the trials whether his religious ethnicity had affected his work during the prosecution. He said he didn’t think his revulsion or desire for justice were any different than that of his non-Jewish colleagues.

After returning from Nuremberg, Meltzer joined the Law School faculty and became a leading scholar in labor law. He was also the first director of the Law School’s Jury Project.

But the experience of Nuremberg stayed with him — and it has become a small piece of the Law School’s history. At his memorial service in 2007, Douglas G. Baird, the Harry A. Bigelow Distinguished Service Professor, remembered Meltzer as “the stuff of legend.”

Said Baird: “From Nuremberg to Rwanda, from the 1940s to 9/11 and beyond, his understanding of war crimes and all the difficulties associated with them made him the clearheaded and unflinching voice of reason.”

Read the first installment of Throwback Thursday: "Let's Make a Deal, Good Sir: Hiring the Law School's First Faculty."