For the Shame of Rose of Aberlone

Remembering the Rhymes of Brainerd Currie

Throwback Thursday is an occasional feature offering glimpses into the Law School’s rich history.

It isn’t every day that one encounters a poet/law professor, much less one who has employed 350 lines of comic verse to toast contracts law, the doctrine of mutual mistake, and a nineteenth-century tussle over an unexpectedly pregnant cow.

But in the 1950s, the Law School had Brainerd Currie, a noted scholar on conflicts of law, the father of the late Professor David P. Currie—and, as it so happened, a writer of rhymes laced with witty commentary on the law and legal education.

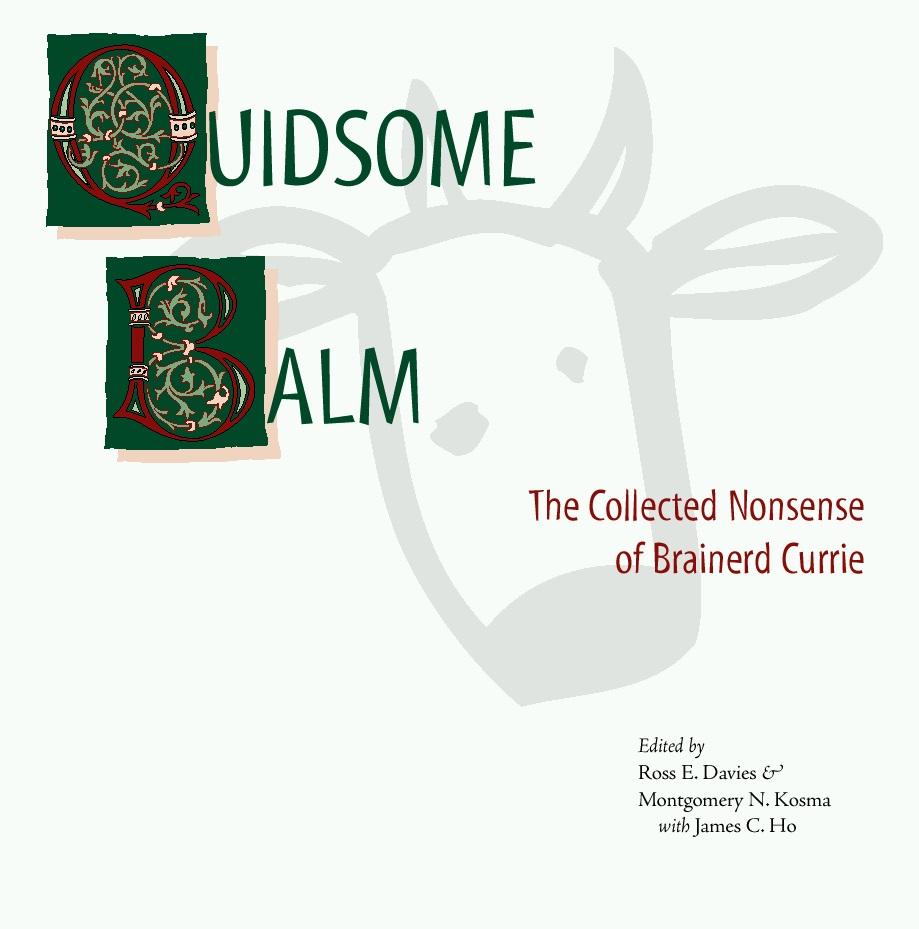

“I am sure that for Currie putting cases in poetic form … seemed as natural a thing to do as briefing them,” wrote Mercer University law professor Jack L. Sammons in the introduction to Quidsome Balm: The Collected Nonsense of Brainerd Currie, a 7-by-7-inch book published by the Green Bag in 2000. “For Brainerd’s love of verse developed at the same time as his love for the law.”

Currie, a member of the University of Chicago Law School faculty between 1953 and 1961, had apparently developed his passion for poetry as a young man. He referred to his own work as “rhymes” or, in at least one case, a “bit of doggerel,” and those who knew him said his forays into poetic humor reflected an appreciation for language and storytelling.

“His approach to each case was to narrate it well first,” the late Walter Blum, a longtime Law School professor, once told Sammons, now a professor emeritus at Mercer. “Only in the process of narrating, only by starting cleanly with the facts, could the right issues emerge in their right relationships.”

Currie’s poetic output seemed to coincide with the publication of some of his most important articles on the conflicts of law, Sammons wrote, noting that it was a “period of truly extraordinary creativity.”

The pieces fit what Green Bag Editor-in-Chief Ross E. Davies, ’97, calls the “Currie tradition of legal-lyrical brilliance,” something that first came to Davies’ attention in the autumn of 1994 when the younger Currie, who taught at the Law School for 45 years, played his guitar and sang on the last day of Civil Procedure. (David Currie’s appreciation for words is also evident in a mesmerizing reading of the entire United States Constitution, which he recorded in 2006).

It was this legal-lyrical tradition that Green Bag editors had in mind when they decided to broaden their offerings in 2000, a few years after the journal’s founding.

“What better place to start than with the Curries, father and son?” said Davies, a professor at Antonin Scalia Law School at George Mason University. David Currie was one of four original UChicago advisers to the Green Bag—along with professors Richard Epstein, R.H. Helmholz, and Dennis Hutchinson—and so the editors asked him what he thought.

“He revealed that there was indeed a trove of useful and entertaining material,” Davies said. “With his guidance and support—and a lovely book design by Green Bag editor Monty Kosma, ’97—we put it together into the little book titled (at David's suggestion), Quidsome Balm. It's been through two printings so far, and we may not be far from a third.”

The younger Currie wrote the book’s preface, explaining that many of his father’s poetic works were “rhymed paraphrases of exotic cases”—a description borne out by the material that followed. In “Tenebrous Reflections,” the subject was the badly botched circumcision at the center of the 1953 case Bates v. Newman. (“It has never been published before, and chances are pretty good it will never be published again,” David Currie wrote of the rhyme). In “Eino, a Sailor,” the elder Currie expounded on Koistinen v. American Export Lines, a case involving a seaman who was injured jumping out the window of a Yugoslavian brothel. And in “Casey Jones Redivivus,” Currie recounted a 1957 US Supreme Court case, Ringhiser v. Chesapeake & Ohio Railway, involving an engineer who lost a leg while relieving himself in a gondola car. The 24-stanza poem begins with the unsettled engineer, Boyd Ringhiser, recounts arguments and Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter’s wish to deny certiorari, and ends with the Court’s verdict:

Old Felix wanted to dismiss the cert.;

There was nothing novel in the case but dirt.

But don’t give up until you’ve heard the end,

For the Su-preme Court’s the gandy-dancer’s friend.

The cases approve any port in a storm,

And in railroad practice it is not bad form

To improvise in an emergency;

This a really prudent railroad sure should foresee.

Su-preme Court rendered its decision,

Su-preme Court, reason sharp and clean;

Su-preme Court said railroads should envision

That a hogger’d use a rattler for a durned latrine.

Others, including “I Thought I Made a Better Grade in Torts,” focused on the law school experience. Some were published in the Green Bag before appearing in Quidsome Balm, and some are available in the collection of Brainerd Currie Papers at the University of Chicago Library’s Special Collections Research Center.

Currie’s best-known poetic turn, though, was his ode to the not-so-infertile cow, Rose 2d of Aberlone, at the center of the 1887 Michigan Supreme Court case, Sherwood v. Walker. As first-year Contracts students know, Hiram Walker had agreed to sell his supposedly barren cow to Theodore Sherwood for beef. But then Rose turned up pregnant, her value rose—and Walker tried to back out of the deal. The Michigan Supreme Court ultimately ruled that because the contract was based on the mutual mistake over Rose’s fertility, Walker could keep his with-calf cow.

Currie wrote about the case in 1950 in his five-section poem, “Aberlone, Rose of: Being an Entry for an Index,” for the amusement of his students at UCLA, where he was teaching law at the time. It is written in the style of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “Christabel,” with a hint of Ogden Nash thrown in—both of whom Currie references in text that appears at the beginning. Currie apparently revised the rhyme over the years, eventually adding seventeen footnotes with comments such as: “Pun. (Hardly original)” and “The author is aware that testosterone is the male sex hormone, and hence that the choice of words is not ideal” and “Look it up for yourself.”

His final version, which appeared in 1965 in The Student Lawyer Journal, is one that he declared would be the last, “so that I will never have to fool with it again.”

It begins with a sad Rose:

‘T is the middle of the night on the Greenfield farm

And the creatures are huddled to keep them from harm.

Ah me! — Ah moo!

Respectively their quidsome balm

How mournfully they chew!

And one there is who stands apart

With hanging head and heavy heart.

Have pity on her sore distress,

This norm of bovine loveliness.

…

If one should ask why she doth grieve

She would answer sadly, “I can’t conceive.”

Her shame is a weary weight like stone

For Rose the Second of Aberlone.

And it ends with a legal legacy that would follow law students for generations:

A dismal specter haunts this wake—

The law of mutual mistake;

And even the reluctant drone

Must cope with Rose of Aberlone.

…

In fiddles of dubious pedigree,

In releases of liability,

In zoning rules unknown to lessors,

In weird conceits of law professors,

In printers’ bids and ailing kings,

In mutations and sorts of things,

In many a subtle and sly disguise

There lurks the ghost of her brown eyes.

That she will turn up in some set of facts is

Almost as certain as death and taxes:

For students of law must still atone

For the shame of Rose of Aberlone.