Giving Back to the Next Generation of Teachers and Students

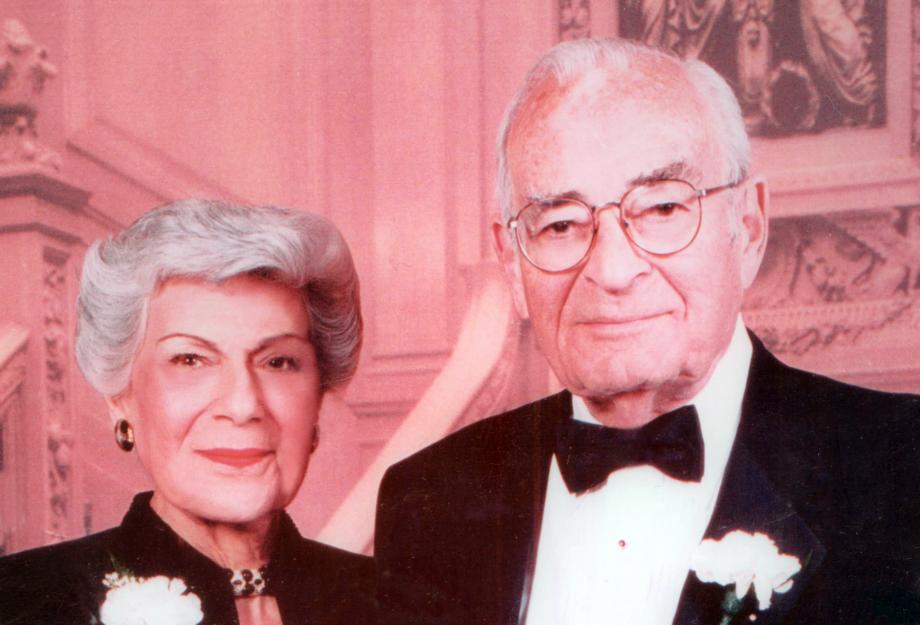

A bequest from Arthur Kane, AB ’37, JD ’39, and his wife, Esther, will support the funding of two positions, a research chair and a teaching chair. The Arthur and Esther Kane Research Chair and the Arthur and Esther Kane Teaching Chair will be faculty members who have demonstrated expertise in constitutional law and/or administrative law.

“When I went to the University, it was supposedly a hotbed of communism, but it was in fact a very balanced education,” Mr. Kane says. “At the Law School, I loved studying constitutional law, and I got my highest grade in that course, which was taught by Kenneth Sears from a centrist perspective. In recent years, there has been such a change in the concept of the Constitution and its flexibility. And of course administrative law has become a major forum. I want to be sure that students can learn those subjects in the balanced, mainstream way that I learned them as a law student.”

Mr. Kane’s name will be familiar to many in the Law School community: his $3 million gift in 1996 made possible the Arthur Kane Center for Clinical Legal Education, one of the most important buildings in the Law School’s history. His name is also recognized throughout the broader legal community, a legacy of the firm he cofounded and guided for more than 40 years, the multiple precedent-setting cases he argued, legislation he influenced, and professional organizations he led.

Mr. Kane’s father, Henry, immigrated to the United States as a teenager, earned a college degree and a law degree, and became a pioneering workers’ compensation attorney. “He would always tell me,” Mr. Kane says, “‘If I accomplished what I did, you can do even better—You’re going to go to the University of Chicago and get the best education possible.’ And he was right: The College was great, and the Law School really challenged me and matured me. The faculty included names like Levi, Sharpe, Bigelow, Sears, Moore, and Cleveland—legal giants, every one of them.”

He also recalls his adventures with a future Law School faculty giant, Walter Blum. As fraternity brothers in 1938, they created the first-prize-winning entry in that year’s Homecoming competition, a theatrical production called “The Munich Follies,” in which each line of dialog consisted of the first line from a popular song.

Not long after graduating (at the age of 21), he married his first wife, Bernice, to whom he was wed for 40 years until her passing. He joined the army in 1942 and served for more than three years during the Second World War. When he returned, he joined his father’s law practice, and they worked together until his father’s passing in 1963. He formed the firm that became Kane, Doy & Harrington in 1965, and it became a preeminent workers’ compensation practice, principally on the defense side.

“We tried to keep the firm small,” Mr. Kane recalls, “but I guess we were doing a good job, because cases kept coming in.” He recalls that at one time the firm’s ten attorneys had nearly six thousand active cases, and the firm often was handling as many as ten percent of all of the workers’ compensation cases in Illinois. His legal successes helped burnish the firm’s reputation, as his arguments established important precedents. He became a recognized expert on occupational diseases—for plaintiffs, he won the first asbestosis case in Illinois and also gained a major victory in a myasthenia gravis case. He served as president of the Illinois Workers’ Compensation Lawyers Association and as chair of the Chicago Bar Association’s committee on workers’ compensation, among several other major institutional roles.

Mr. and Mrs. Kane celebrated 30 years of marriage in April. Together and separately, they have been generous benefactors to a wide range of causes, including the University of Chicago, the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago (where Mr. Kane is a life trustee), Northwestern Medical School, and service-dog organizations for veterans and for people who are visually impaired or hearing impaired. They funded the Arthur and Esther Kane Legal Clinic at the Chicago Lighthouse, the only clinic to provide free legal services exclusively to blind and visually impaired people.

“My parents were right,” Mr. Kane says. “Going to the University of Chicago Law School made a huge difference in my life. I think they would be very proud, and that means a lot to me.”